“A Poem Found Written on a Rock at the American River” / Photo by Bruce Donehower

A North American Zoom Meeting for the Section of the Literary Arts and Humanities!

On Sunday September 19, 2021, at 1 pm Pacific Time, the collegium of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities of the School for Spiritual Science in North America will host an online event for friends and members of the Section. This one-hour Zoom event will consist of a brief overview of recent events in the Section, followed by a panel discussion and some time for questions and answers.

UPDATE (September 21, 2021): The meeting was a success! Visit this summary to read about the event. More North American meeting of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities are in the planning stage. Send your comments and suggestions by using the Contact Page on this site.

A panel consisting of members of the collegium of the North American Literary Arts and Humanities Section will discuss from a personal perspective the topic:

“How does my life interest in anthroposophy support and inspire my love for and practice of literature and the humanities? How does my study of literature and the humanities inform my life interest in anthroposophy?”

The panel members are Bruce Donehower (California), Arie van Amerigen and Robert McKay (Canada), Gayle Davis (California), Fred Dennehy (New Jersey). Herbert Hagens (New Jersey) will participate from the audience.

Contact me by email if you want to receive the Zoom credentials to participate in the meeting.

To prepare for this event, I assembled some materials related to the History and Mission of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities.

“Tell Me More . . .”

Virgo. Book of Hours. 1470

Rudolf Steiner’s “First Address” / Notes Toward an Understanding of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities

Those who follow the posts on this website may remember that at the Section meeting on March 6, 2021, we looked again at Rudolf Steiner’s “First Address” – a lecture that Steiner gave in Vienna in 1889 that has the title Goethe as the Founder of a New Science of Aesthetics.

Christoph Lindenberg refers to this lecture as Rudolf Steiner’s “first” in the chapter titled “Ästhetik” in Vol 1 of Lindenberg’s Steiner biography. Another lecture that gets tagged as Rudolf Steiner’s “first” is the one from September 29, 1900, in Berlin that carries the title “Goethe’s Secret Revelation” (Schmidt No. 0091). This is a lecture given to theosophists. Of related importance to this lecture is Goethe’s Fairy Tale of the Green Snake and Beautiful Lily.

Both “First Addresses” are concerned with the same topics: Goethe and Beauty.

Much attention has been given to Rudolf Steiner’s Last Address of 1924 in which he discusses Novalis and the 21st century. Comparatively less attention has been devoted to the First Address in which Steiner discusses Beauty. Beauty is of course especially important, some have suggested, for an understanding of the purpose and identity of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities — known in German as the Section for Beautiful Sciences.

Beauty and Aesthetic Theory

While not so much a barn-burner topic of interest with the American mindset recently, Beauty and aesthetic theory are important topics in the European early romantic literary tradition upon which and within which anthroposophy finds itself situated. We have discussed this at our previous meetings, such as the one June 14, 2021 in which Fred Dennehy presented Owen Barfield.

The questions arise: Why did Rudolf Steiner in the 1889 First Address put emphasis on Beauty? Or, if we prefer to date the First Address later, one can ask the same question regarding the role of Beauty in Goethe’s Fairy Tale of The Green Snake and Beautiful Lily.

Beauty and the Mission of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities

When Rudolf Steiner established the first Vorstand following the Christmas Foundation Conference, he appointed Albert Steffen as the leader of the Section for Beautiful Sciences. We’ve discussed Albert Steffen and Steffen’s writings quite a few times in our Section meetings over the past ten years, as for example recently on June 13, 2020 when we explored Steffen’s writings on Novalis and Dante. When Rudolf Steiner appointed Albert Steffen as the first leader of the Section for Beautiful Sciences, he said:

“In the Anthroposophical Society we are fortunate to have a splendid representative of the Beautiful Sciences among us: Albert Steffen. Not only is he called to be the leader of the Section for the Beautiful Sciences, but also to re-enliven this branch of human creativity, which has been left in the corner, much to the detriment of civilization.”

— Rudolf Steiner; quoted by Heinz Matile in “Albert Steffen and the Beautiful Sciences” in the 2002 Yearbook of the Literary Arts and Humanities

Rudolf Steiner gave many indications to help us understand how he envisioned the work of the other Sections of the School for Spiritual Science, but he never gave a lecture cycle that clarified his understanding of the work of the Section for the Beautiful Sciences. And of course, even the German name for this Section catches most people on the back foot when they hear it in English. “Beautiful Sciences? Say what? Is this like, uh, Goethe doing watercolors? Does Steiner mean belles-lettres? Probably he meant belle-lettres!”

Hmm . . . Well, not really . . . In fact, he had trouble figuring it out. Here is Rudolf Steiner in discussion, thinking aloud:

“And then we need to consider: First, something – I mentioned it already [on December 25] – still called belles-lettres in France, perhaps. I do not know if this expression is still current. No? It’s too bad! Into the nineteenth century – then it disappeared – people in Germany spoke of the Beautiful Sciences that brought beauty into the sphere of human knowledge, aesthetics, the artistic. It is quite characteristic that even in France the expression belles-lettres is no longer known.”

Comment from the audience: “Académie des lettres!”

“Yes, but the belles has been left out. And that’s the main point. We have enough sciences . . . but Beautiful Sciences! I do not know what the scientists here—especially the younger ones—say about this, but here in Dornach we are not just connected to the most recent past; we are even connected to the most distant past. And that is why we can and must create a Section here for the area called belles-lettres in France and Beautiful Sciences in Germany, even if later we will have to find a title for it that the world finds more comfortable—I haven’t found one yet.”

— Rudolf Steiner; quoted by Heinz Matile in “Albert Steffen and the Beautiful Sciences” in the 2002 Yearbook of the Literary Arts and Humanities

Might one suspect from these remarks that Rudolf Steiner saw our Beautiful Sciences Section as a Section on a quest of spiritual self-discovery? Might one suspect that he deferred here to the poets?

Strong Words!

Here in North America, where we share a broad community of languages, our Section chose to name itself the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities. Some believe this was done in part to avoid the confusion and inelegance of a literal translation of the German name. It is interesting that the name belles-lettres was not chosen, despite the active presence of the Canadian French language community in the Section. As Steiner suggested, the name belle-lettres may not be quite adequate. It orients us backwards in time not forward, he opined. It is another relic of the nineteenth century. Nothing wrong with the nineteenth century or looking backward, of course! In fact, we do that all the time when we read literature, don’t we? We compare and contrast old books and poems and argue about details of interpretation and make ironic quips – among other activities. Such activities include translation, editorial work, publishing, scholarly critique, history, art history, media studies, HTML, linguistics, aesthetics, humanities, philosophy, philosophy of science, the teaching of writing, the teaching of novels and poetry and critical theory . . . And the list continues.

All sober and worthy scholarly-scientific intellectual pursuits.

But let us not forget the heart! Let us not forget creative writing! Let us not forget the poets and novelists and dramatists! It is interesting that the person whom Steiner appointed to lead the Section at its founding was a creative writer, primarily.

“The Germans, by the way, are such odd people! They make life more difficult than is proper by looking for deep thoughts and ideas everywhere and putting them into everything. —Good gracious! Have the courage for once to surrender yourselves to your impressions, allow yourselves to be captivated, moved, uplifted . . . but don’t always think everything is vain that isn’t some abstract thought or idea!”

— Goethe, from Conversations with Eckermann

A History of the Section in North America

“Who are These People? Why am I Here?”

— Hamlet, lines from the rejected manuscript

Over the summer, I personally took up this question of Section purpose and activity once again. I spent time this summer re-reading selections from GA 32 and essays from the 2002 Section Yearbook. The title of GA 32 in English is “Methodological Foundations of Anthroposophy.” It is a collection of essays that Rudolf Steiner wrote in the 1880s and 1890s during his literary period – that period of activity prior to Rudolf Steiner’s activity with Theosophy. It includes the “First Address” that I mentioned earlier.

Some have suggested that this literary period of Rudolf Steiner’s biography is a good place to start research if we want to understand the assumptions underlying Rudolf Steiner’s statement that the beautiful sciences have been neglected “much to the detriment of civilization.”

As we move forward into the remainder of 2021 and then forward toward 2023 and 2024, my hope is to continue to investigate these First Addresses and the related writings – along with other materials that provide literary context and background to an understanding of our Section—its meaning and purpose. I hope others join the conversation!

To get the conversation started, I did a quick translation for my own benefit of the introduction to GA 32.

Label warning: Rudolf Steiner digresses and spends a considerable amount of this introduction in discussion of Ernst Haeckel.

“Art in Nature” from the work of Ernst Haeckel

“Ontogeny Recapitulates Phylogeny” Ex-squeeze me?

Ernst Haeckel is a person we haven’t discussed in our Section meetings yet, but he is a person of curiosity and controversy for the literary student of “Beauty” – if only for Haeckel’s natural-scientific illustrations and what these might suggest about nature’s aesthetic intelligence, so-called. Haeckel’s racist and ideological / cultural prejudices require critical reading and alert cross examination – in fact they involve us in an important area of discussion that makes some friends and members extremely nervous. The topic moves us once again back into the nineteenth century and exposes us to its “shady side,” to use the generous term of critique that Steiner applied to Haeckel’s character in Steiner’s introduction to GA 32. Back in the day when I taught a semester course on the Grail for Sunwest University at the Rudolf Steiner College, we spent an entire class session or two on Haeckel and Steiner’s reading and use of Haeckel – although admittedly, this is not a subject to excite a parade.

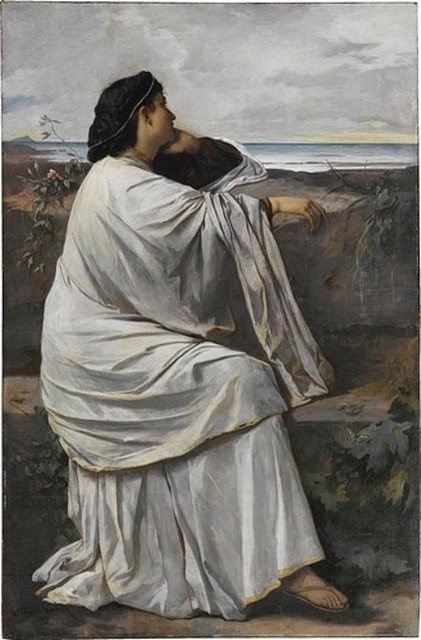

“Iphigenie” (1871) by Anselm Feuerbach

“All Work and no Play makes Jack a Dull You-know-what.”

— Apocrypha falsely attributed to F. Schiller

My Summer with Goethe (and Rilke)

As I mentioned in the last post I’ve idled through most of my summer with Goethe, believe it or not. I traveled to Italy with him; I re-read his early lyric poems; I translated and then recorded one of these early poems with my wife; I re-familiarized myself with the West-eastern Divan and with the splendid erotic poems that Goethe wrote after he returned from Italy; I eavesdropped again on conversations between Goethe and Eckermann; I re-appreciated Goethe’s taste in wine; attended a class reunion of the School of Hard Knocks with Wilhelm Meister; hung out with Iphigenie in Tauris; argued with Faust; and I worked my way through a few Goethe biographies.

In our post-modern Covid world, this might strike some as a curious or quixotic waste of time. Why not devote attention to contemporary voices in literature?

Are we Americans? Or what are we doing here anyway?

As I walked through the dried-out grasslands at the American River and surveyed the drought-stricken oaks and sniffed the late summer vinegar weed and discovered poems written on rocks and tacked on trees, I asked myself the same question – and not for the first time.

The answer is always the same. I spend time with secular humanist literature and with writers like Goethe and Novalis who speak from that tradition because I want to understand the origins and development of anthroposophy from a literary standpoint. When Rudolf Steiner recommends Goethe to my attention, I take him seriously. Just as I take him seriously when he recommends Novalis to my attention.

I feel obligated to read the primary texts and do the work.

“Storms and Stresses”

Goethe the Poet

As an artistic offering from the summer musings, here’s a video of one of the early poems by Goethe. It’s read by my wife Marion, and I accompany Marion on the classical guitar. The music is by Catalan composer Fernando Sor (1778 – 1839).

You might remember Sor’s music from other Fairy Tale Videos that we’ve done as part of the Section work in Fair Oaks. A translation of Goethe’s poem “Welcome and Departure” follows. In this translation, I tried to preserve the rhyme scheme of the original poem, for better or worse. Eh? You’ll see a line by line translation of the Goethe poem as Marion speaks.

(By the way, if any of you out there do martial arts, particularly the ones that teach joint locks, take note of how the woman has hold of the young man’s hand. In aikido, we call that a sankyo variation, and it will lift the partner’s energy and uproot him or her, as is happening here. So you might think that his heart is broken, but it’s actually just “tough love.”)

“Summer Light” / photo by Bruce Donehower

“You, my friend, are lonely . . . “

“Sonnet to Orpheus” / Part 1, Sonnet 16

Written for a Dog.

Also, this summer I composed another musical setting for one of Rilke’s sonnets to Orpheus as part of the ongoing Section-inspired Rilke Project. I translated the poem so that folks will understand what Marion is saying when she recites the poem in German. You’ll see the line-by-line translation in the video as Marion speaks.

Our group in Fair Oaks has been working with the poet Rilke for the past few years. You can find more information on Rilke and Sonnets to Orpheus by clicking this sentence.

Publication Announcement!

I’ve always taken seriously the fact that creative writing stands at the exact center of our Section from the time of the First Vorstand. Early this fall I will release a revised and re-written edition of my novel The Singing Tree: An Alchemical Fable, a creative project that I have lived with and re-imagined since I first encountered anthroposophy through Rene Querido. My style of working on this novel has been a bit in the manner of Goethe’s style of working – bursts of activity followed by procrastination, delay, endless dithering and rewriting, trips to sunny locations to excite the imagination or chase exciting beauties, half-hearted or enthusiastic sharing of the work in progress with friends, obsessive devotion to an ideal of completion . . . until finally the “sleepwalker” arrives at a destination. (Goethe referred to his poet-process as sleepwalking, by the way.) This new edition of the novel is forthcoming from Sage Cabin Publishers and will be available as e-book and trade paperback. The publication is now available. Click this sentence to preview or order.

“The Singing Tree can’t be put down; it is immediately engaging. This is a first-rate work, witty and observant and with a central character one can’t help but believe in and care about, a work that is genuinely of/for the imagination. It is an ecological story, a coming-of-age story, a time-travel story, a philosophical story . . . And it stays with me into sleep, during sleep, on waking up, it is still unfolding . . .”

— Professor Jane Hipolito

Report from the Fairy Tale Group

Marion has written a report on the meetings of the Fairy Tale Group. The group has met regularly for three months this summer. Click this sentence to read what is happening in the Secret Garden.

Zoom Meetings in Fair Oaks Resume September 18

Our first meeting of the Michaelmas semester will be a poetry night. Poets will share original poetry or original translations or poetry, and poetry lovers will share a favorite poem, if there is time after the poets do their thing. I’ll send the credentials to interested persons on the 17th. Click this sentence to read about previous Section-sponsored Poetry Nights.

Last but not Least . . .

Here is a link to the New Moon Salon “Fairy Tale of the Month” for September.

____________

“Now, however, there arose within me something which demanded meditation as a necessity of existence for my mental life. The striving life of the mind needed meditation just as an organism at a certain stage in its evolution needs to breathe by means of lungs.”

— Rudolf Steiner, from The Course of My Life, chapter 22

“My heart commanded: “Ride!”

No sooner felt — alight!

The earth in evening’s tide

And on the mountain, night.”

— Goethe, from the poem Welcome and Departure

I started Early – Took my Dog –

And visited the Sea –

The Mermaids in the Basement

Came out to look at me –

— Emily Dickinson, from poem 656

“The past gathered out of the darkness where it stayed, and the dead raised themselves to live before him; and the past and the dead flowed into the present among the alive, so that he had for an intense instant a vision of denseness into which he was compacted and from which he could not escape, and had no wish to escape. Tristan, Iseult the fair, walked before him; Paolo and Francesca whirled in the glowing dark; Helen and bright Paris, their faces bitter with consequence, rose from the gloom. And he was with them in a way that he could never be with his fellows who went from class to class, who found a local habitation in a large university in Columbia, Missouri, and who walked unheeding in a midwestern air.”

— John Williams, from the novel Stoner