"Pratiquez l'observation de l'esprit !

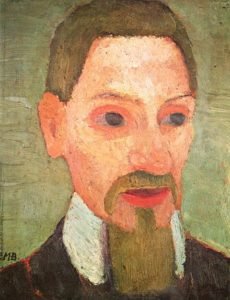

Œuvre d'art : Marion Donehower (Section des arts visuels)

Rainer Maria Rilke / Paul Cézanne

Chers amis,

L'un des aspects uniques de notre section des arts littéraires et des sciences humaines est son lien très étroit avec les arts visuels et les sciences humaines. Section des arts visuels.

La plupart d'entre vous savent que notre chef de file de la section du 21e siècle Christiane Haid (qui s'est jointe à nous pour nos conférences nord-américaines en 2024 et 2025)) est le chef de file de la Section des arts visuels de l'école des sciences de l'esprit au Goetheanum, ainsi que le chef de file de notre Section des arts littéraires et des sciences humaines (appelé Section des belles sciences en allemand). En plus de ses activités littéraires et de ses recherches en sciences humaines, Christiane est artiste peintre.

La créativité artistique a toujours été d'une importance capitale pour notre section ....

Mais vous ne savez peut-être pas (ou vous avez peut-être oublié) que la personne choisie par l Rudolf Steiner car le premier responsable de notre section était aussi un artiste visuel, en plus de ses autres talents de poète, de romancier et de dramaturge.

Je parle de Albert Steffen.

"Albert Steffen était anthroposophe avant même d'être né.

- Rudolf Steiner, lors de la Conférence de Noël, le 24 décembre 1923, à 11 h 15 du matin

"Dire quoi ?" Albert Qui?

Albert Steffen est une personne dont le nom et les activités ne sont plus aussi bien connus de nombreux amis en Amérique du Nord.

Certaines personnes se sentent même très mal à l'aise ou nerveuses lorsque le nom d'Albert Steffen est évoqué. Cela est souvent dû aux souvenirs qu'ils ont de l'histoire d'Albert Steffen. les années très difficiles et traumatisantes chargées de crises après la mort de Rudolf Steiner Il y a plus de cent ans, lorsque la Société générale fondée par Rudolf Steiner à l'Institut de l'Université d'Helsinki, en Allemagne, a été créée. Conférence de Noël s'est déchirée.

Peut-être que maintenant que nous sommes en le deuxième centenaire de la mort de Rudolf Steiner il est temps d'examiner cette situation dans les années 1930 et 1940 au sein du mouvement et de la société, car elle met en lumière un thème d'une grande importance existentielle, qui est ... .

Amitié spirituelle

L'un des thèmes de recherche permanents de notre section, qui se réunit régulièrement en Californie du Nord depuis 2010, est le suivant Amitié spirituelle. Au fil des ans, nous avons consacré plusieurs réunions à des discussions sur l'amitié spirituelle : par exemple, l'amitié entre les hommes et les femmes. Goethe et Schiller, Mary Wollstonecraft et William Blake, Novalis et Ludwig Tieck. Nous avons également étudié l'amitié entre Albert Steffen et Percy MacKaye, poète et dramaturge américain; père de Arvia MacKaye Ege et Christy MacKaye Barnes. Percy, comme Albert, est largement ignoré ou marginalisé de nos jours, mais pour des raisons différentes.

Lors de diverses réunions au fil des ans, J'ai essayé de mettre en évidence Percy MacKaye et sa famille élargie. Je l'ai fait pour relancer une discussion sur l'histoire de notre Section et sur l'histoire du mouvement anthroposophique au 20e siècle. L'amitié spirituelle de Percy MacKaye (et d'autres membres de la famille MacKaye, dont Henry Barnes) avec Albert Steffen est très importante pour l'histoire de notre Section ... ainsi que pour l'histoire de la Société dans le contexte du mouvement anthroposophique. années de crise du vingtième siècle après la mort de Rudolf Steiner en mars 1925.

Il s'agit d'un sujet délicat, chargé de drames et de contradictions performatives. ... peut-être digne d'un jeune romancier, dramaturge ou scénariste, qui n'a pas encore trouvé sa voix ou son public.

Je reviendrai sur ce thème de l'amitié spirituelle entre Albert Steffen et Percy MacKaye dans des rencontres et des billets ultérieurs. Gardez un œil sur ce site. Mais entre-temps...

Rainer Maria Rilke ; Paul Cézanne / Deux essais d'Albert Steffen

Je souhaite partager avec vous deux essais d'Albert Steffen extraits de son livre Buch der Rückschau [Livre de recueillement], publié en 1938. Ceux-ci ont été publiés précédemment dans le Journal de l'Anthroposophieaujourd'hui disparu. J'ai choisi ces essais parce qu'ils illustrent l'amitié spirituelle entre notre section des arts littéraires et des sciences humaines et la section des arts visuels. Nous avons discuté de cette étroite amitié entre les arts visuels et les arts littéraires lorsque nous avons étudié le poète anglais William Blake. Et lorsque nous avons étudié Blake, nous avons même introduit la musique dans la discussion. Patricia Dickson, membre du conseil d'administration de la section des arts visuels, a interprété deux chansons de Blake Chansons d'innocence et d'expériencedes chansons composées expressément pour la voix de Patricia Dickson.

Peut-être lors d'une prochaine Salon New Moon réunion du groupe de la section de Californie du Nord, des poèmes d'Albert Steffen ou de Percy MacKaye peuvent également être chantés ?

"Je sais que ce monde est un monde d'imagination et de vision... mais tout le monde ne voit pas de la même façon. Aux yeux d'un avare, une guinée est bien plus belle que le soleil, et un sac usé par l'usage de l'argent a de plus belles proportions qu'une vigne remplie de raisins. L'arbre qui fait pleurer de joie les uns n'est aux yeux des autres qu'une chose verte qui fait obstacle. Mais aux yeux de l'homme d'imagination, la nature est l'imagination même. Tel l'homme est, tel il voit. . . Pour moi, ce monde n'est qu'une vision continue de la fantaisie ou de l'imagination..."

- William Blake, dans une lettre au révérend John Trusler, 1777

Deux souvenirs

par Albert Steffen

"Un poète et un peintre

Premier recueil

Le poète Rainer Maria Rilke

Mes rencontres avec Rainer Maria Rilke se situent dans les années de guerre (1914-1918), que j'ai passées à Munich. Dans le petit restaurant où je prenais mon repas de midi, je m'intéressais depuis longtemps à un client qui apparaissait sporadiquement, s'asseyait discrètement à une table solitaire et consommait à la hâte, sans se préoccuper de ce qui l'entourait, un repas simple, pour repartir ensuite. L'air à la fois discret et distingué de cet inconnu insaisissable m'a tout de suite plu, mais je n'ai jamais cherché à savoir qui pouvait bien se cacher derrière cet extérieur, car moi aussi j'aimais passer incognito. Pourtant, à cet égard, les deux solitaires étaient très différents. Rilke réfléchissait en son for intérieur. Depuis ma jeunesse, j'avais l'habitude d'observer attentivement, et cela avait été aiguisé par mes études scientifiques, de sorte que j'avais pris l'habitude de dessiner les visages des gens - profil et forme, inclinaison de la tête, attitude et geste - et seulement ensuite je me tournais vers l'humeur, cherchant à partir de là à pénétrer dans les qualités intérieures qui se manifestaient comme une coloration de l'âme.

Rilke ne posait guère les yeux sur les gens qui entraient et sortaient de l'endroit, bien qu'il y eût parmi eux des personnages très intéressants. J'en ai conclu qu'il s'agissait d'une habitude qu'il avait probablement prise en ville (Schwabing, où il vivait, ne pouvait guère être considérée comme une ville), ou d'un moyen d'autoprotection, car son regard, qui était doté d'une qualité de recherche, attirait toute son âme et, pour ne pas être blessée dans sa sensibilité, devait nécessairement se garder d'être retenue prisonnière.

De plus, lorsque j'ai rencontré l'étranger dans d'autres situations, en particulier dans le jardin anglais, il est apparu comme quelqu'un qui avait un penchant pour entendre plutôt que pour voir.

Or, ce qui est particulier, c'est que pour rendre justice à cette figure, le sens de l'observation intérieur a dû chercher de nouvelles formes d'expression. Ainsi, j'étais souvent amené à me dire : "Ce front est comme une tour. Le guetteur y voit une armée d'esprits planant au-dessus de sa tête, mais ce ne sont pas les anges de la chrétienté, mais ceux de l'Islam".

La bouche est également remarquable.

Il rappelait un barbeau [une sorte de poisson-chat], avec ses longs fils ressemblant à des barbes, que j'aimais tant regarder quand j'étais enfant, lorsqu'il restait suspendu dans l'eau claire de la source tandis que les vagues ondulaient sur le lit pierreux scintillant.

Soudain, je compris aussi la lueur, tantôt brillante, tantôt ombrageuse, qui jaillissait de ces yeux - l'alternance intérieure de la confiance et de la crainte. Un esprit qui est libre et qui sent pourtant qu'une certaine terreur pèse sur lui !

Mais de quoi ce poète avait-il peur ? D'être arraché à son milieu d'origine ?

Bien sûr, à ce moment-là, je savais qui il était et il avait aussi appris mon nom.

Un jour, Rilke, de dix ans mon aîné, s'assit brusquement à ma table et commença à parler d'une pièce de théâtre que lui et moi avions vue la veille au soir : De l'aube à la nuit" de Georg Kaiser. On raconte que Rilke l'avait déjà vue cinq fois. Il s'agissait de salutistes [chrétiens de l'Armée du Salut] qui manquaient à leur devoir. Nous avons ensuite discuté de la relation entre la parole, l'action et la doctrine.

J'ai parlé d'un ami qui avait obtenu un doctorat en histoire de l'art et qui était devenu officier de l'Armée du Salut. La conversation s'est ensuite orientée vers la guerre. Rilke a raconté comment le peintre Kokoshka, qui était un de ses amis, avait vécu sa première attaque dans les dragons. Il avait mis ses mains sur les yeux de son cheval pour les protéger.

Lorsque, au cours de la conversation, j'ai fait remarquer que la connaissance affectait ma poésie de manière productive, il s'est tu et j'ai senti son opposition. Il m'aurait semblé indélicat de citer les mots de Goethe :

"... par une secrète tournure psychologique, ou un état d'esprit, qui mériterait peut-être d'être étudié de plus près, je crois m'être élevé à une espèce de production qui, en pleine conscience, a donné naissance à ce qui trouve encore aujourd'hui mon approbation, sans que je puisse peut-être jamais nager à nouveau dans la même rivière - oui, un état d'esprit auquel Aristote et d'autres prosateurs attribueraient une sorte de folie."

- Goethe, cité par Steffen

Cette tournure psychologique secrète m'était connue depuis longtemps ; je l'avais trouvée récemment, rendue digne de confiance par la connaissance, dans les œuvres de Rudolf Steiner. Sans son exercice, me disais-je, la force créatrice des futurs poètes serait vouée à se tarir ou à être engloutie par les conquêtes de la science technique qui s'imposent de plus en plus. Je considérais la méthode appliquée par Goethe dans la métamorphose des plantes comme une aide pour éveiller et maintenir en vie les forces naissantes de l'âme. Il m'a semblé qu'elle serait également bénéfique à Rilke qui, à cette époque, se sentait souvent abandonné par son génie.

Naturellement, je ne pensais pas qu'une quelconque forme d'entraînement puisse jamais remplacer la poésie pure. C'était, et c'est resté, la grâce. Malgré cela, le grain des dieux poussait, plus facilement, même si cela passait inaperçu, sur un champ entretenu quotidiennement par un tel exercice.

Rilke s'est également formé lui-même, mais pas dans ce domaine de la connaissance. Malgré l'admiration que l'on peut éprouver pour sa poésie, cette qualité incertaine lui reste attachée. Ainsi, par exemple, une étrange contradiction traverse son œuvre, qui touche à l'intuition la plus profonde et la plus complète du destin, le fait des vies répétées sur terre. D'une part, on dit de lui qu'il était convaincu "d'avoir vécu à Moscou dans une incarnation antérieure", alors que dans les Élégies de Duino, il insiste comme une incantation sur le fait que la vie sur terre n'existe qu'une fois :

". Pourquoi alors

et pourquoi, en éludant la question de l'âge de l'homme, nous

notre destin, aspirent-ils encore à ce même destin ? ...

Oh, pas parce que la chance existe,

qui précipitent les gains et annoncent les pertes à venir.

Pas par curiosité, ni comme un devoir de cœur,

comme s'il pouvait lui aussi battre dans le laurier ....

Mais parce qu'il est important d'être ici, et parce que tout ce qu'il y a ici,

bien qu'éphémère, a apparemment besoin de nous - d'une manière étrange

nous concerne. Nous, les plus éphémères d'entre nous. Une durée de vie

pour chaque chose, unique. Une fois et pas plus.

Et pour

nous aussi,

une seule fois. Jamais plus. Mais ceci

avoir été, même si ce n'est qu'une fois :

ce qui a été le propre de la terre, semble être irrévocable".

- Rainer Maria Rilke, extrait de la Neuvième Elégie de Duino / trad. Alfred Corn

On annonçait alors une conférence de Rudolf Steiner sur la représentation des qualités qui, dans l'art, sont à la fois révélées aux sens et suprasensibles. De ma place, j'ai eu l'occasion d'observer Rilke, qui était assis parmi le public, et je devais presque supposer que, comme cela lui arrivait souvent à cette époque, il ne se sentait pas à l'aise.

Le lendemain, j'ai rencontré Michael Bauer et d'autres connaissances dans notre restaurant. Pendant des années, j'ai été très attaché à l'ami le plus fidèle de Christian Morgenstern. Dans mon journal, on peut lire cette phrase à propos de Bauer : "Croire en un homme, c'est être solidaire de son moi supérieur".

L'assemblée était en train de discuter de la conférence de Rudolf Steiner lorsque Rilke entra. Tout le monde voulait savoir ce qu'il en pensait. Après quelques hésitations, je fus persuadé d'aller le voir, comme il l'avait fait pour moi peu de temps auparavant. J'ai pensé qu'une telle visite pouvait être envisagée.

Sans se prononcer sur l'exposé de Rudolf Steiner, Rilke commence à développer ses propres idées sur notre lien avec le suprasensible. "Nous recevons des impressions par les sens, dit-il, par l'œil, l'oreille, le goût. Entre ces sens, il y a des "vides" qui sont encore remplis chez les peuples primitifs, mais qui sont morts chez nous." Sur une serviette en papier, il dessine un cercle qu'il divise en secteurs distincts, en les ombrant alternativement, de sorte qu'il en résulte une sorte de disque avec des caractères cunéiformes noirs. "Il est nécessaire de rendre ces parties cultivables", poursuivit-il. "Cela nous donne suffisamment de travail." Et il se mit à parler de l'œuvre de Huysman. Symphonie d'odeurs.

Je me réjouissais que la nouvelle vie qui devait être apportée aux facultés flétries devait surgir à un stade plus élevé - hors de la sphère de la cognition, non de la sensibilité - par des moyens qui étaient ouverts à tous et non plus le privilège d'une poignée de privilégiés.

C'est là que j'ai pris conscience de cette opposition intérieure et que j'ai gardé le silence.

La panthère

Sa vision, à partir des barres qui défilent sans cesse,

s'est tellement fatiguée qu'elle ne peut plus tenir

rien d'autre. Il lui semble qu'il y a

mille barreaux, et derrière les barreaux, pas de monde.

En faisant les cent pas dans des cercles étroits, encore et encore,

le mouvement de ses foulées puissantes et douces

est comme une danse rituelle autour d'un centre

dans laquelle une volonté puissante reste paralysée.

Parfois seulement, le rideau des élèves

se lève, sans bruit-. Une image entre,

se précipite vers le bas à travers les muscles tendus et bloqués,

plonge dans le cœur et disparaît.

- Rainer Maria Rilke (traduit par Stephen Mitchell)

Deuxième recueillement

Le peintre Paul Cézanne

Lors de l'Exposition d'été de 1936 où, trente ans après la mort de Cézanne, plus de 180 de ses tableaux étaient rassemblés dans l'Orangerie du Jardin des Tuileries à Paris, plusieurs souvenirs étaient visibles juste à l'entrée : La dernière palette de Cézanne, son sac à dos, des lettres illustrées à Emile Zola, ainsi qu'un crâne humain et un Cupidon qu'il a souvent dessinés ou peints.

Ces reliques intimes sont contemplées avec une absorption révérencieuse. Elles sont natures mortesL'esprit vivant, le témoignage de l'esprit vivant.

La palette n'a été utilisée par lui que deux jours avant sa mort, lorsqu'un orage l'a surpris à son travail et a provoqué la maladie qui a causé son décès. La peinture blanche, pressée du tube, a l'apparence d'une chrysalide de papillon, mais elle est devenue dure et grise ; l'orange ressemble à de l'argile croulante du bord du chemin ; l'éclat a disparu du rouge ; le bleu est devenu sombre ; tout n'est que terre de lave sans vie.

Le regard du visiteur descend ensuite le long des pièces suspendues jusqu'à la pièce la plus éloignée, dont le mur du fond est occupé par le chef d'œuvre de Cézanne, le tableau géant, Les Grandes Baigneuses.

Bien qu'inachevée, elle porte en elle le caractère de l'achèvement. Les huiles sont manipulées comme des aquarelles, de sorte que les teintes prédominantes de ce nuage d'effusion - les bleus et les verts - semblent avoir été créées à partir de leur propre élément, de l'eau elle-même. "Tout naît de l'eau", dit Thalès, "tout naît de l'air", dit Anaximandre. Mais pour les philosophes présocratiques de Milet, les éléments étaient encore dotés d'une âme.

La beauté, issue de la nature divine, ne s'exprime plus chez Cézanne de manière architecturale comme chez les Grecs, mais par un mouvement rythmique ; ses formes sont devenues en même temps des sons. L'image est plutôt composée que construite, mais elle n'en est pas moins strictement conforme à la loi.

La forme triangulaire, caractéristique du fronton de marbre du temple grec, est ici poussée vers le haut par la puissance arboricole, courbée vers l'extérieur et ouverte vers le sommet. Dans les quatorze figures féminines qui, minces comme des troncs d'arbres, sont groupées parmi eux, c'est plus l'harmonie de la croissance que la proportion des membres qui est rendue. On peut ainsi imaginer le bosquet sacré d'un peuple ancien avec son culte de la vie. A travers les arbres brille un ruisseau, qui éveille en nous le désir de voyager à Arcady, car sur sa surface liquide plane, malgré les rives visibles à l'œil nu, le sens d'un rêve d'antan.

Un peintre capable de créer un tel tableau à une époque comme la nôtre, qui voit les choses si différemment, porte dans son œil non seulement l'image extérieure qui est projetée sur la rétine, mais aussi un pouvoir d'illumination provenant de sa nature profonde et remontant à un passé lointain. Cette image n'est pas pensée par l'intellect, mais elle est atteinte avec un degré de profondeur qui ne s'est déployé que par une pratique inlassable et par de lents degrés. C'est la même capacité que l'on peut déceler chez les grands dramaturges lorsque, avec une soudaineté inattendue, ils parviennent au tournant critique de leurs tragédies. On sent dans cette œuvre des éléments mystérieux de l'époque pré-chrétienne et on est ramené des milliers d'années en arrière.

Et l'on s'émeut à la pensée de cette tempête qui submergea Cézanne lors de sa dernière œuvre. Pour lui, les mêmes éléments à partir desquels il a créé la plus grande composition de sa vie, ont apporté la mort.

À côté de la palette, avec ses vestiges de couleur, se trouve le sac à dos brun jaunâtre qui l'accompagnait dans ses promenades à la campagne.

Elle est si éloquente que l'on visualise instinctivement les épaules qui l'ont portée.

C'est là aussi que se trouve la tête de mort, et l'on cherche des preuves de l'usage qu'en a fait Cézanne. Sa réplique peinte se trouve avec deux autres (I'rois têtes de mort) sur un tapis oriental présentant un motif de fleurs aux couleurs pourpre-brun de la même taille que les sombres orbites. Ces creux, à côté des fleurs à la lumière sombre, font penser à de sombres tourbillons, aspirant les yeux..

Il s'agit d'une nature morte post-mortem. Sur la richesse du tissu, les têtes de mort produisent un effet non seulement de mort mais de mort, comme une mort potentialisée, la "seconde mort" dont parle saint Paul, que le Christ ressuscité a pu contempler après la crucifixion.

Cézanne revient toujours sur ce sujet. Il remonte à sa "période sombre", lorsqu'il préférait le brun, le blanc et le noir dans ses tableaux. En 1876, il avait déjà peint une nature morte avec une tête de mort. Même à un âge avancé, il ne pouvait se soustraire à ce modèle. On raconte que pendant des semaines, il y a travaillé plusieurs heures par jour, de 6 à 10 heures du matin, comme s'il voulait en changer la couleur et la forme presque tous les jours.

Le fait que Cézanne ait été enclin à peindre le même thème pendant de longues périodes consécutives n'est nullement dû à un manque d'imagination, mais plutôt aux profondeurs inépuisables de son âme. Il se livre à de tels exercices non pas de manière naïve (comme un enfant qui n'a jamais assez d'un conte de fées), ni de manière pieuse (comme un saint qui se plonge de plus en plus profondément dans la prière), mais en tant qu'artiste en quête de connaissance, qui fait de lui-même et de son sujet un sujet d'étude. Il médite sur le motif pictural. Grâce au renforcement de l'âme qu'il a ainsi obtenu, l'oeil intérieur, nourri par le sang (et qui, chez les passionnés, s'assombrit), s'est aiguisé, tandis que l'oeil extérieur, mécanisme physique qui ne donne que des images-miroirs sans vie, s'est vivifié. Cézanne a ainsi pu, l'un des premiers, assurer la transition entre l'époque sombre du XIXe siècle et la nouvelle illumination, processus typique des peintres les plus en vue de cette période.

Dans son "Nature morte avec l'horloge en marbre noir". la noirceur de la première époque de Cézanne trouve une expression symptomatique. Le temps semble s'être arrêté.

Il est significatif que ce motif soit pris dans la chambre de Zola. C'est dans leur prime jeunesse que Zola et Cézanne se sont rencontrés, et le destin a voulu que le célèbre peintre représente le célèbre écrivain avec le regard que ce dernier a porté sur son époque, un regard qui n'est pas encore illuminé de l'intérieur mais qui rayonne d'une volonté de vérité inébranlable.

Zola, tel qu'il est représenté par Cézanne, est l'enquêteur observateur et libre d'esprit, le publiciste qui se bat fanatiquement pour la justice. Le tableau dont je parle ("Le poète Alexis lisant à Zola")) est de la même époque que la "Nature morte à l'horloge de marbre noir", peinte vers 1868. Zola est assis sur un coussin blanc, vêtu de blanc. Ses vêtements, malgré leur banalité, ont un charme étrange. Sa pose, qui suggère le recueillement plutôt que le repos, fait involontairement naître la pensée : il aurait pu s'agir d'un Arabe.

Le fait que Cézanne peigne Zola non pas sur un tabouret comme Alexis - que l'on voit de profil à gauche du tableau, accroupi plutôt qu'assis, le manuscrit à la main - mais presque au niveau du sol, comme dans une mosquée, où l'on ne trouve ni tabouret ni banc, n'a certainement pas qu'une signification artistique.

Dans cette pièce, tout est nu. Zola, avec une expression concentrée mais ouverte, tient sa tête en avant et légèrement penchée. Une main pend négligemment, un genou est replié. Il apparaît ainsi comme un calife qui s'est émancipé d'Allah et qui a transféré à la plume la volonté de combattre qui passait autrefois par l'épée ; il apparaît comme le père du naturalisme. Sa tête dépasse un seuil situé dans son dos et pénètre dans un espace allongé, très sombre et étroit, coupé par le haut. Malgré l'effet abstrait des surfaces sombres et claires géométriquement divisées, le tableau est inquiétant, son austérité oppressante. Mais Cézanne a réussi à apporter de la lumière dans l'obscurité qui, plus tard, étouffera Zola. C'est comme si son œil avait puisé la vitalité dans les sens qui n'étaient pas encore privés de leur propre vie, le goût et le toucher, comme s'il s'était transformé en organe de vie. La fleur de géranium, d'un rose terne, est presque palpable sur les lèvres, tandis que la surface verte et rugueuse des feuilles invite presque à la caresse du bout des doigts. Dans le paysage derrière, l'ombre a disparu du vert. Le rouge clair brille. La montagne se dissout dans une brume bleu-violet. La lumière qui envahit l'espace en élargit les limites, mais l'effet n'est pas celui d'une dissolution ou d'un brouillage, malgré l'extension incompréhensible, mais plutôt celui d'un approfondissement et d'un renforcement.

Les contours de la terre restent définis.

Les bruns de Cézanne sont des plus purs, le brun de la terre, du maïs et du pain. On accède partout à un monde éthéré. Comme la mer, les collines et les bois nous paraissent désormais paradisiaques !

Le monde nous est présenté à nouveau - l'arbre, la pomme cueillie sur une assiette, l'assiette elle-même, à côté d'elle le couteau, la bouteille, la tasse, la nappe ; chaque objet, qu'il soit sur la table de cuisine ou sur le piano. La pipe en terre dans la bouche du joueur de cartes peut être goûtée visuellement.

Des gens que l'on ne remarque guère dans la vie quotidienne, des ménagères, des paysans, ont été tellement transformés par une touche de bleu-vert ou de bleu-violet que l'on ne se lasse pas de les contempler. Et son épouse, cette bonne âme au visage ovale, nous impose le respect.

Et puis, il y a la montagne, Sainte Victoire. On reconnaît ici la tâche confiée à Cézanne par les dieux eux-mêmes : la peindre à plusieurs reprises jusqu'à ce que celui qui la contemple puisse l'emporter avec lui comme un but pour toute sa vie et l'au-delà. Que la terre tombe en poussière, l'image peinte par cet artiste restera. Ce qu'il a fait de la montagne avec ses heureux paliers de couleur, du jaune orangé au rouge violet, nous pouvons le conserver ; il nous a présenté un but - la nouvelle terre.

Il est remarquable que l'on puisse emporter plus que ce que l'on a vu sur ces toiles. Car si l'on ferme les yeux et que l'on se représente la galerie, l'espace visuel derrière les paupières est rempli non seulement des paysages, des portraits et des natures mortes que l'on a vus, mais aussi de beaucoup d'autres êtres qui se mêlent à eux.

Et maintenant, le maître lui-même se tient devant nous. "Venez, dit-il, il y a encore de belles choses à peindre.

Il soulève le sac à dos et le boucle sur ses épaules. On voit qu'il y a des ailes. . . Il s'envole.

6.19.25