“Temple Veil” de Marion Donehower (Section des arts visuels)

Entretien avec l'artiste Marion Donehower de Stil Magazine

Chers amis,

Marion Donehower est membre du groupe de direction de la section nord-américaine des arts littéraires et des sciences humaines de l'École des sciences de l'esprit et a participé à la planification des conférences de la section nord-américaine en 2024 et 2025. Elle est également membre de la section des arts visuels.

Son interview a été publiée dans le numéro d'été 2025 de la revue Stil Magazine, un numéro intitulé "Art et guérison". Stil est une publication en langue allemande, mais la traduction anglaise de l'interview de Marion est incluse ici, ainsi que des photos de l'article en allemand. et un lien vers l'article allemand PDF. Cliquez ici pour obtenir des informations sur Stil Magazine.

Marion facilite le travail de notre section nord-américaine Groupe FairytaleElle est également artiste-interprète. Vous pouvez découvrir une partie de son travail sur la poésie de Rilke ici.; ou cliquez ici si vous voulez profiter de la lecture du conte de fées de Novalis par Marion Atlantis avec les artistes de la section Margit Ilgen et Patricia Dickson; ou cliquez ici pour voir son interprétation du conte de Hermann Hesse La métamorphose de Piktor en anglais ou en allemand.

"L'ART NOUS OUVRE LES YEUX SUR LE MONDE SPIRITUEL.

UNE CONVERSATION AVEC MARION DONEHOWER

INTERVIEW ORIGINALE EN ALLEMAND DANS STIL MAGAZINE ; ÉTÉ 2025

Cliquez ici pour voir un PDF en allemand de l'interview et de l'œuvre d'art de Marion

Vous êtes né et avez grandi en Allemagne, vous êtes allé aux États-Unis après l'école, puis au Japon, et maintenant vous vivez à nouveau aux États-Unis. Comment ces trois pays jouent-ils un rôle dans l'histoire de votre vie ?

Je suis née en Allemagne. Cependant, j'ai toujours été intéressé par le Japon parce que j'ai grandi dans le bouddhisme. Mon père se rendait souvent au premier centre bouddhiste allemand à Hambourg, la "Haus der Stille" (Maison du silence), et je l'accompagnais. Ainsi, dès mon enfance, j'assistais souvent à des conférences sur le Dharma et j'apprenais à connaître le chemin bouddhiste vers la paix intérieure. Ma mère se qualifiait elle-même de "taoïste goethéenne". Elle faisait beaucoup de randonnées avec moi et me montrait la nature, mais elle ne connaissait pas le nom des plantes. Elle aimait aussi jouer du violon et était triste que je ne veuille pas jouer d'un instrument. Il y avait toujours des discussions dans la maison de mes parents. Les questions existentielles étaient à l'ordre du jour, et mon père était également un adepte de Schopenhauer et de Nietzsche et était très enthousiaste à l'égard de l'art. J'étais fasciné par ces conversations et j'ai appris très tôt que les livres renfermaient de grands secrets. Mais bien sûr, j'étais une enfant, et une enfant qui aimait le mouvement, qui aimait la gymnastique et l'équitation.

Dans les années 1960, jeune assistante sociale, je cherchais à donner un sens à ma vie. J'avais entendu parler du tai-chi, un art du mouvement chinois, et j'avais été initiée à l'aïkido, un art du mouvement spirituel japonais plus récent. La méditation assise ne m'attirait pas, mais la méditation en mouvement m'a immédiatement touchée. C'était clair : c'était ce que je cherchais, c'était ma vie. Au bout d'un an, lorsque j'ai eu suffisamment d'argent de côté, je suis allée à Honolulu, à Hawaï, où j'ai pratiqué le tai-chi tous les jours dans un temple bouddhiste. Sur le chemin du retour à Hambourg, je me suis arrêté à Boston, qui était à l'époque le centre mondial de la macrobiotique, et j'étais très intéressé par la macrobiotique japonaise enseignée par Georges Osawa et d'autres professeurs japonais. T.T. Liang, un important professeur de tai-chi, vivait à Boston. Je suis devenue son élève et j'ai ensuite enseigné moi-même dans cette ville. C'est là que j'ai rencontré mon mari, Bruce Donehower, qui était mon élève. Il a obtenu un poste de conférencier dans une école de langues au Japon. Je me suis donc retrouvée au beau milieu du Japon, à Hamamatsu. Sur les étagères de l'appartement où nous vivions, je n'ai trouvé que des livres japonais. Les seuls livres en anglais disponibles étaient ceux de Rudolf Steiner. J'ai commencé à lire et je n'ai pas pu m'arrêter. Je me sentais très étrangère au Japon, isolée, et les textes de Rudolf Steiner m'ont fait comprendre encore plus clairement que j'étais européenne. Et pourtant, un lien avec le Japon s'est développé et perdure encore aujourd'hui. Vous pouvez le voir dans mes peintures.

Au bout d'un an, nous sommes retournés aux États-Unis et avons déménagé à Fair Oaks, en Californie. C'était en 1982 ! Fair Oaks disposait d'un collège pour la formation des enseignants Waldorf, d'une école Waldorf, d'une clinique médicale anthroposophique et de magasins. C'était (et c'est toujours) un véritable village anthroposophique.

Quand la peinture est-elle entrée dans votre vie ? Les chemins qui y mènent sont-ils aussi sinueux que ceux qui mènent à votre lieu de résidence ?

À Hambourg, j'ai vécu avec des artistes et j'étais mariée à un étudiant qui était l'élève de Joseph Beuys. Je n'avais jamais pensé à peindre moi-même. Je connaissais toutes les galeries les plus importantes d'Europe et j'avais approfondi ma compréhension de l'art, mais je n'ai découvert la peinture qu'au Rudolf Steiner College de Fair Oaks. Ted Mahle, un élève de Beppe Assenza, a éveillé ma joie de peindre.

Plus tard, j'ai suivi un séminaire de quatre ans avec un peintre de calques réputé, ce qui n'a pas été facile pour moi. J'aimais les aquarelles, mais je devais soudain les apprivoiser et devenir pédant. Cette technique me paraissait immobile et rigide, je n'étais pas sûre de moi !

Cependant, le professeur qui m'a le plus aidé à réunir les fils de l'aïkido et de la peinture a été la chirurgie du cerveau. Lors d'un entraînement d'aïkido, un jeune homme à qui j'enseignais m'a projeté si violemment au sol que j'ai subi une commotion cérébrale. Un médecin m'a alors diagnostiqué un neurinome acoustique, une tumeur bénigne du nerf auditif. Après son ablation, j'ai perdu l'équilibre et je n'entendais plus que d'une oreille. J'ai dû réapprendre à marcher, je ne pouvais plus me servir de mon bras droit et je ne pouvais ni écrire ni peindre. J'ai dû repartir de zéro, comme un petit enfant.

J'ai alors commencé à peindre de la main gauche, j'ai réappris à marcher et j'ai commencé à pratiquer l'aïkido avec beaucoup de précautions et avec l'aide de mon mari. C'est à travers ces limitations physiques que j'ai découvert mon art.

Vous aimez expérimenter dans vos peintures. Comment se déroule le processus de peinture ?

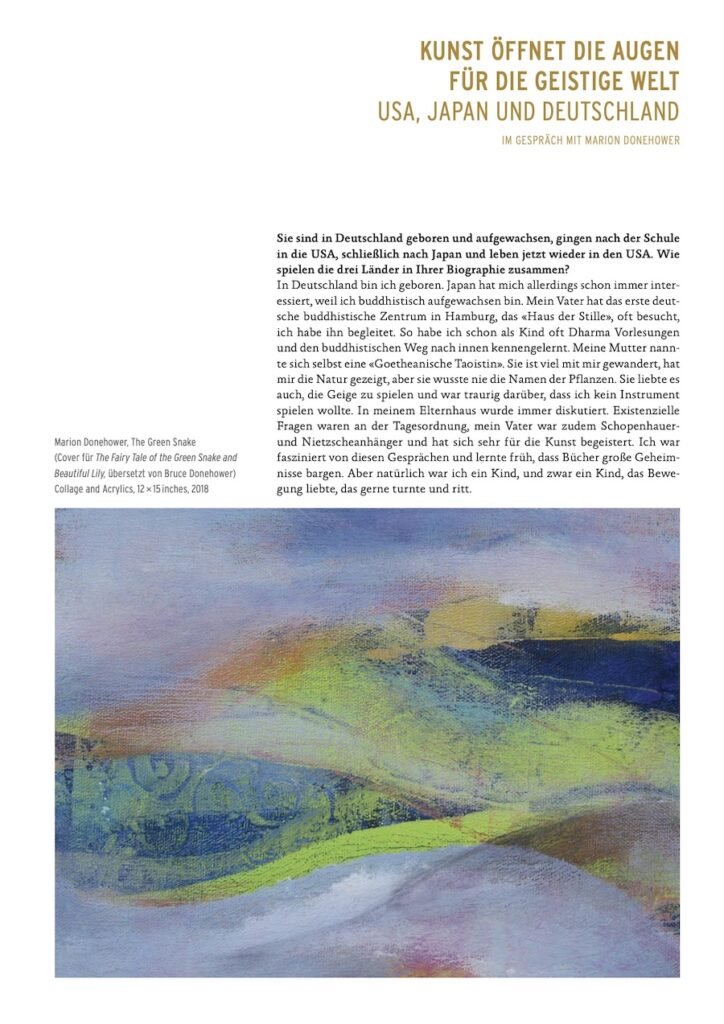

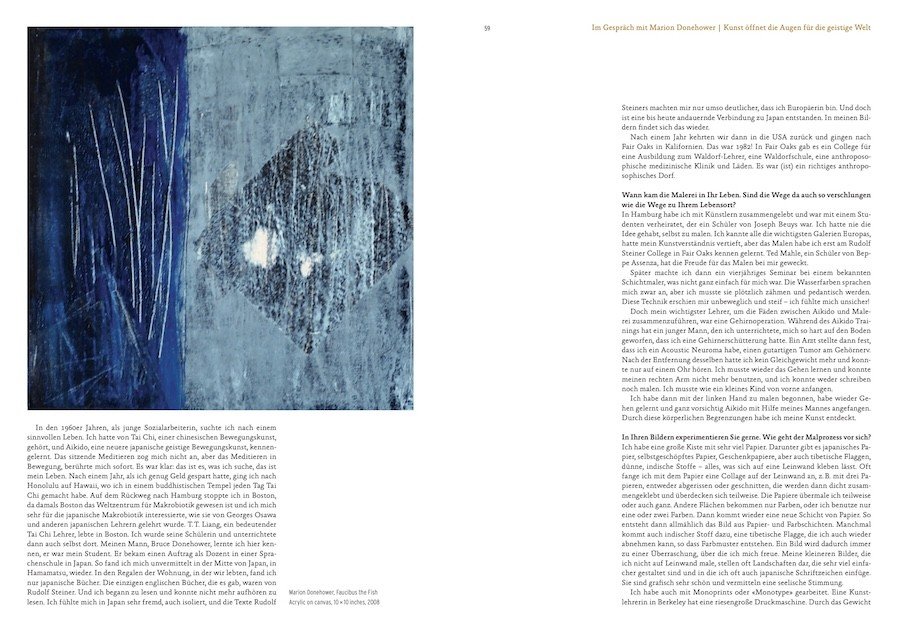

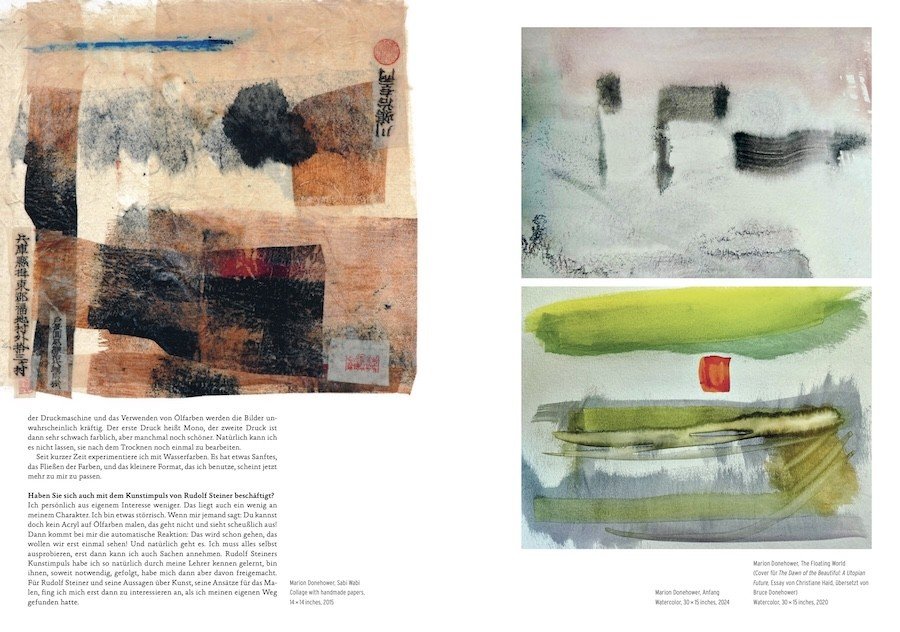

J'ai une grande boîte avec beaucoup de papier. Elle contient du papier japonais, du papier fait main, du papier d'emballage, mais aussi des drapeaux tibétains, de minces tissus indiens - tout ce qui peut être collé sur une toile. Je commence souvent par faire un collage sur la toile avec le papier, par exemple avec trois morceaux de papier, déchirés ou coupés, qui sont ensuite collés étroitement les uns aux autres de manière à ce qu'ils se chevauchent partiellement. Je peins sur une partie du papier, partiellement ou entièrement. D'autres zones sont simplement colorées, ou je n'utilise qu'une ou deux couleurs. J'ajoute ensuite une autre couche de papier. Peu à peu, l'image émerge des couches de papier et de peinture. Parfois, j'ajoute un tissu indien ou un drapeau tibétain, que je peux retirer à nouveau pour créer des motifs de couleur. Cela signifie qu'une image est toujours une surprise, ce qui me réjouit. Mes tableaux plus petits, que je ne peins pas sur toile, représentent souvent des paysages beaucoup plus simples et dans lesquels j'insère souvent des caractères japonais. Ils sont graphiquement très beaux et transmettent une atmosphère spirituelle.

J'ai également travaillé avec des monotypes. Un professeur d'art à Berkeley possède une énorme presse à imprimer. Le poids de la presse et l'utilisation de peintures à l'huile rendent les images incroyablement vivantes. La première impression s'appelle un mono, et la deuxième impression est très peu colorée, mais parfois encore plus belle. Bien sûr, je ne peux pas résister à l'envie de les retravailler une fois qu'elles sont sèches.

J'ai récemment commencé à expérimenter l'aquarelle. Il y a quelque chose de doux dans l'écoulement des couleurs, et le petit format que j'utilise semble mieux me convenir maintenant.

Avez-vous également a exploré l'impulsion artistique de Rudolf Steiner ?

Personnellement, cela m'intéresse moins. C'est aussi un peu dû à mon caractère. Je suis un peu têtu. Si quelqu'un me dit : "Tu ne peux pas peindre à l'acrylique sur de la peinture à l'huile, ça ne marche pas et c'est affreux !", ma réaction automatique est : "Ça va marcher, voyons !". Et bien sûr, ça marche. Je dois tout essayer par moi-même, de manière " ", avant d'accepter les choses. J'ai naturellement connu l'impulsion artistique de Rudolf Steiner par le biais de mes professeurs, je l'ai suivie autant que nécessaire, mais je m'en suis ensuite détachée. Ce n'est qu'après avoir trouvé ma propre voie que j'ai commencé à m'intéresser à Rudolf Steiner et à ses déclarations sur l'art, à ses approches de la peinture.

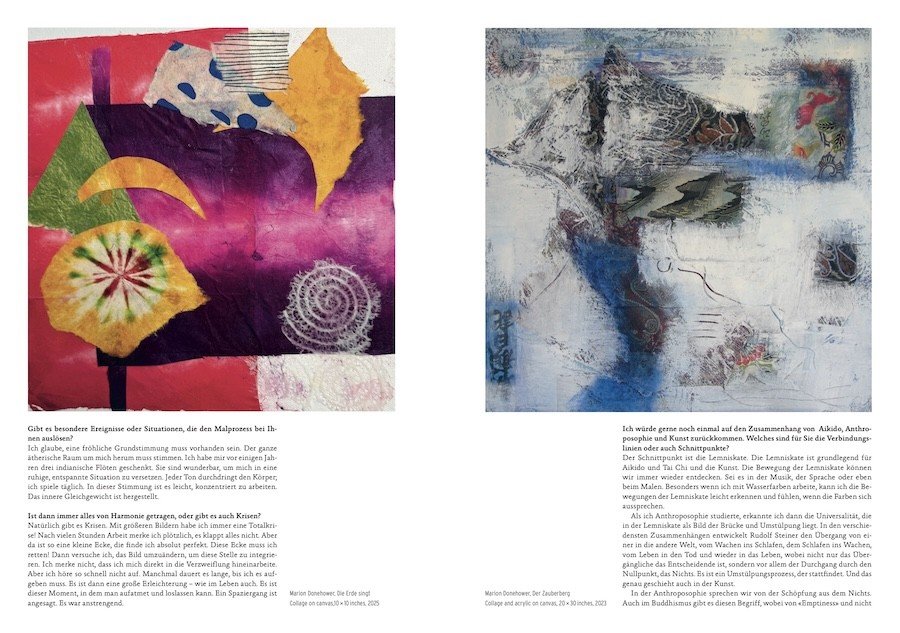

Y a-t-il des événements ou des situations particulières qui déclenchent chez vous le processus de peinture ?

Je crois qu'il faut que l'humeur soit joyeuse. Tout l'espace éthéré qui m'entoure doit être bon. Il y a quelques années, je me suis acheté trois flûtes amérindiennes. Elles sont merveilleuses pour me mettre dans un état de calme et de détente. Chaque note pénètre le corps ; j'en joue tous les jours. Dans cet état d'esprit, il m'est facile de me concentrer sur mon travail. Mon équilibre intérieur est rétabli.

Tout est-il toujours harmonieux ou y a-t-il des crises ?

Bien sûr, il y a des crises. Avec les grandes images, c'est toujours la crise totale ! Après de nombreuses heures de travail, je me rends soudain compte que rien ne fonctionne. Mais il y a un petit coin que je trouve absolument parfait. Il faut que je le garde ! J'essaie alors de modifier l'image pour intégrer cet endroit. Je ne me rends pas compte que je suis en train de me désespérer. Mais je n'abandonne pas facilement. Parfois, il me faut beaucoup de temps avant de devoir abandonner. C'est alors un immense soulagement, comme dans la vie. C'est le moment où l'on peut à nouveau respirer et lâcher prise. Une promenade s'impose. C'était épuisant.

J'aimerais revenir sur le lien entre l'aïkido, l'anthroposophie et l'art. Quelles sont les lignes de connexion ou les intersections pour vous ?

L'intersection est le lemniscate. Le lemniscate est fondamental pour l'aïkido, le tai chi et l'art. Nous pouvons découvrir le mouvement de la lemniscate encore et encore. Que ce soit en musique, en langage ou même en peinture. En particulier lorsque je travaille avec des aquarelles, je peux facilement reconnaître et sentir les mouvements du lemniscate lorsque les couleurs s'expriment.

Lorsque j'ai étudié l'anthroposophie, j'ai reconnu l'universalité de la lemniscate en tant qu'image d'un pont et d'une inversion. Dans les contextes les plus divers, Rudolf Steiner développe le passage d'un monde à l'autre, de la veille au sommeil, du sommeil à la veille, de la vie à la mort et au retour à la vie, où ce n'est pas seulement le transitoire qui est décisif, mais surtout le passage par le point zéro, le néant. C'est un processus d'inversion qui a lieu. Et c'est exactement ce qui se passe dans l'art.

En anthroposophie, on parle de création à partir du néant. Ce concept existe également dans le bouddhisme, bien qu'il soit désigné par le terme de "vide" et non par celui de "néant". Mais tout comme le néant n'est pas rien, le vide n'est pas un vide, mais un champ fertile de possibilités créatives infinies qui attendent de naître. En anglais, on parle de "endless conditional arising". Dans un sens thérapeutique, on pourrait aussi parler de la "nuit noire de l'âme". Lorsque nous nous réveillons de cette nuit et que nous franchissons la porte, nous avons la possibilité de découvrir un chemin vers de nouvelles expériences et pensées.

En peinture, j'ai vécu la transition pendant une crise, et après cette crise, un nouveau départ s'est ouvert. En aïkido, le point zéro se trouve dans le processus de respiration. Les mouvements du corps et la respiration flottent entre l'harmonie détendue et l'harmonie tendue - c'est un long chemin de pratique qu'il faut suivre pour atteindre cet état.

Sur quel projet travaillez-vous actuellement ou aimeriez-vous travailler à l'avenir ?

Aujourd'hui, c'est le premier matin de 2025 - un bon jour pour réfléchir à mes projets !

Pour l'instant, je vais travailler avec des aquarelles et apprendre à maîtriser mon papier japonais. Ensuite, j'envisage de créer une grande série de très petites images, d'une taille de 15 x 15 cm seulement. Je les collerai sur du papier japonais et les recouvrirai d'aquarelle. Ensuite, j'ai en tête un projet collaboratif plus important, sur lequel je travaillerai avec d'autres personnes. Nous voulons coller les chutes de papier et autres soi-disant déchets sur une très grande toile dans mon atelier, peindre par-dessus et créer un collage collectif.

Cliquez ici pour voir un PDF en allemand de l'interview et de l'œuvre d'art de Marion

08.03.25