This article first appeared in German in the June 25, 2022 issue of the newsletter Das Goetheanum. It appears on this website for the Section of the Literary Arts & Humanities with permission of the newsletter editor. Read or subscribe to Das Goetheanum!

Essay Translated by Das Goetheanum staff

1921: Year of Crisis

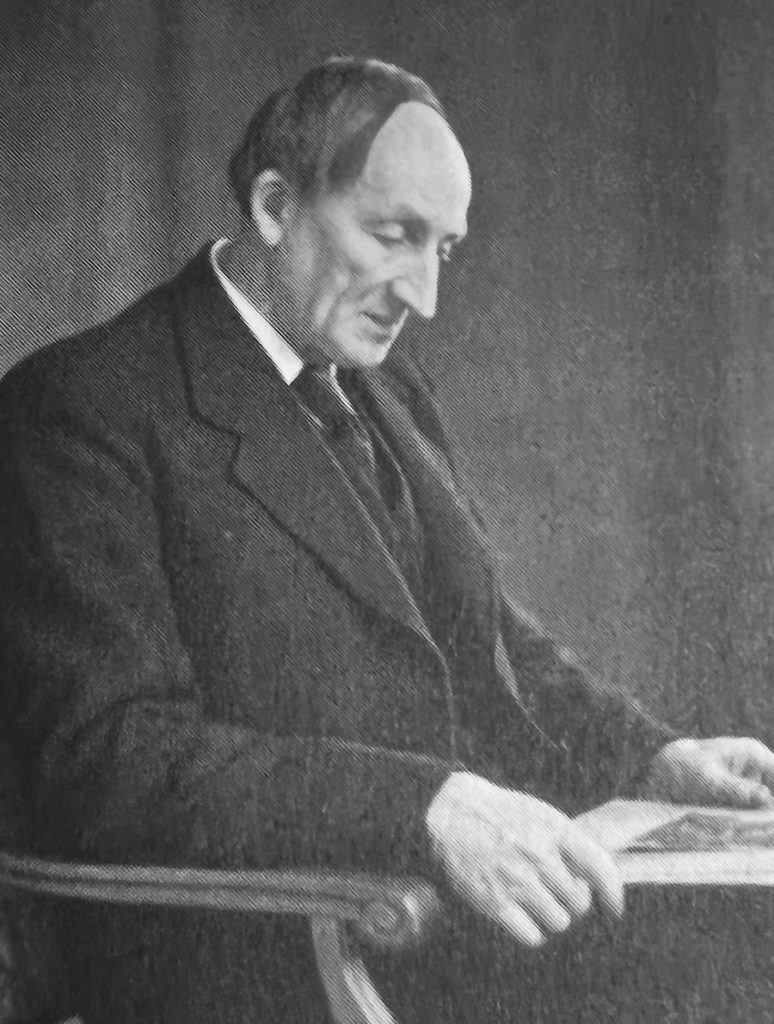

Albert Steffen had taken over editorship of the weekly journal Das Goetheanum, founded in 1921. The personal tragedy associated with this was described in detail by Ruedi Bind in the last study booklet published by the Albert Steffen Foundation. It impresses with a rich selection of documentary evidence — especially the many excerpts from Steffen’s diary, which is an invaluable testimony for understanding the history of the anthroposophical movement. Due to these statements by Steffen, which are touching because of their authenticity, a decidedly vivid image emerges of his existential struggle, which lasted for years and was triggered when he took over the position as editor.

Steffen had previously lived in a rather secluded world of poets and now his editorial work confronted him directly with the outside world and its fiercely fought spiritual battles. The atmosphere was politicized and ideologically heated when the first number of the International Weekly Journal for Anthroposophy and Threefold Order, edited by him, appeared on August 21st 1921. At that time, it was not the village of Dornach but the Catholic town of Arlesheim that was the center of a massive campaign directed against the Goetheanum. In the large inter-Swiss opposing network from the far right to the far left, attempts were made by all means to hinder Rudolf Steiner’s work. In the midst of this raging struggle, 36-year-old Albert Steffen, who saw poetry as his life’s work and actually detested working as a journalist, found himself placed. Now the question arises: Why this sudden radical disturbance in the contemplative, introverted existence as a poet?

This extremely momentous break in Albert Steffen’s professional career caused by assumption of a responsible but unbeloved activity was closely connected with the special constellation of the fates of three other personalities: Roman Boos, Willy Storrer and Rudolf Steiner. Roman Boos, lawyer and driving force of the threefold movement in Switzerland, always had the plan to found a press medium that would represent the anthroposophical view of things. His project, publication of the monthly journal Social Future, had not brought the desired resounding success. The opponents’ declaration of war was to be effectively countered with their own newspaper. He wanted to take over the political part of the editorial office.

Young Willy Storrer, journalist and advocate of the threefold movement also had the desire to start a newspaper. He showed particular interest in cultural events. Although this might appear to be a a good prerequisite for beneficial cooperation, the situation developed quite differently. Roman Boos suffered a mental breakdown and was forced to withdraw from all activities. Willy Storrer’s ambition to take over full responsibility for the newspaper project was firmly rejected by Rudolf Steiner; he limited Storrer’s remit to administrative matters: this was the field in which he was meant to prove himself first. So, what was the situation regarding editorial work? Rudolf Steiner agreed to take over the remit originally intended for Boos — the political-economic field. He wanted Albert Steffen to be the sole editor with an emphasis on the cultural section, and Steffen finally agreed. This is how Albert Steffens and Rudolf Steiner’s “work as editors and journalists” came about – a collaboration impressively described by Bind.

“Why won’t he let me quit?”

— Albert Steffen

Albert Steffen

A Sense Of Impending Disaster

The bright side of Albert Steffen’s work as an editor was his close collaboration with Rudolf Steiner, although here, too, we can see a dark side of things that troubled him. He assessed his abilities as an editor as insufficient. He literally suffered from a “sense of disaster” and complained that the “uncreative” work robbed him of joy.

“I sit there and ponder in vain [what I could write about]. For [writing] is what I have to do. After all, I am employed as an editor. That’s how most of the week passes. The people who come to see me find a tormented and angry person instead of a helper and comforter as before. Yes, I have become a corpse.” (9.4.1924)

On December 6, 1921, he had already asked himself regarding Rudolf Steiner: “Why won’t he let me quit? Why won’t he help me free myself?”

This was Albert Steffen’s big personal fateful question, especially towards Rudolf Steiner. It was difficult for him to understand Steiner’s attitude.

“Broadside” poem by Bruce Donehower

Dedication to the Word

The desire to break out of the confining situation did not prevent Steffen from conscientiously fulfilling his duty as an editor. His commitment even went beyond that. In the following months he did not hesitate to speak out in public — in his capacity as a well-known Swiss poet — in favor of Rudolf Steiner’s naturalization. He composed an appeal, wrote letters to the Federal Council, and also addressed individual Federal Councilors personally. Thereby he fulfilled his public responsibility as editor of Das Goetheanum: to personally stand up for Rudolf Steiner and Anthroposophy. Nevertheless, he saw his actual mission in life, his work as a poet, as impaired – and even endangered.

Threefold Structure of the Weekly Journal

After the Christmas conference and re-founding of the General Anthroposophical Society, Das Goetheanum obtained new inner direction: it was to be at the service of this impulse for spiritual renewal. A new supplement was introduced for members. It was titled: What is Happening Within the Anthroposophical Society. Steffen also assumed editorial responsibility for this newsletter. The corporate structure around these two publications was rather complex; it was basically tripartite. On the one hand, there was the editorial department, which was responsible for spiritual content. Steffen was responsible for this field. On the other hand, there was administration, the economic field. Willy Storrer was responsible for this, but he handled his assignment in this regard quite loosely. The largely autonomous administration was initially economically associated with the Futurum Department of Publishing at the Goetheanum, and later with the Goetheanum Association or its legal successor the General Anthroposophical Society. Then there was still – so to speak in the middle between the two poles – the actual legal entity of Das Goetheanum: editorship. These were institutions with which the newspaper administration was associated. It was a remarkable tripartite institutional model — most interesting for study purposes!

Posted on a bulletin board at Spring Valley, NY

Steffen struggled with Storrer, the responsible administrator or publisher. With him, but also with his colleagues on the executive board and other leading anthroposophists as representatives of the editorial board, he repeatedly came into conflict, feeling restricted in his autonomy as editor. “Editor versus publisher and editor” was a big issue for Steffen according to Bind. His work was essentially shaped by his immediate social environment, which behaved towards him as “helper, inhibitor and inhibiting helper,” according to Bind. In this context, the names Paul Bühler, Roman Boos, Hans Reinhart, and Willy Storrer come up. Bind’s description of these personalities is characterized by fact-oriented objectivity, without embellishment or glorification.

An example of this portrayal: “Willy Storrer, publishing director and administrator, was restless, always on the go, full of himself, and loud, even up to his early death in 1930 in his own sports plane. He could fascinate and motivate others to work with him, not so much to work with him as to work for him. He was always the boss.”

Or: “Roman Boos was a fighter, preferably against something, even more preferably against someone: against those who did not want to understand that social Threefolding was the solution, then against opponents who attacked Rudolf Steiner, then against Pastor Max Kully, who had argued to hinder Rudolf Steiner and prevent the Goetheanum from being built. While Rudolf Steiner was still alive, Boos also fought against Ita Wegman. This vehement struggle shifted towards Steffen after Ita Wegman’s death.”

Only sparse accounts of the time after Rudolf Steiner’s death can be found in Bind’s portrayal. The focus remains on the years from 1921 to 1925. This sense of tension is impressively addressed in the chapter titled The Artist Confronts the Editor and Journalist, and it is documented with quotations. A few days before Rudolf Steiner’s death, the diary contains the beginnings of an emerging understanding of the meaning of the fateful situation: “Dr. Steiner said he had thought long and hard about my question of what to write and suggests that I solve the question of why artists are afraid to become anthroposophists, thinking they are losing their gifts, their unbiased productivity. Not a theorizing task, but an artistic one. I have always felt myself to be a servant. And if someone who has deeper insights than I do finds a job necessary for me, I do it. Even if it were cleaning boots. Isn’t that good?”

[Note from the Editor: Our recent Section meetings have begun to highlight the noteworthy friendship between the American Percy MacKaye and Albert Steffen. Those readers who have an interest in the History of the Anthroposophical Society might wish to become familiar with Percy MacKaye, a poet and dramatist.]

8.7.22