Here is a summary of the recent weekly Section for Literary Arts & Humanities meeting of the local group in Fair Oaks, CA. This meeting occurred on March 14, 2020 In this meeting, we continued our exploration of William Blake and British Romanticism.

This was our last in-person meeting before the Covid event and attendant crisis transitioned our meetings to Zoom. Due to the crisis that appears to be ongoing at this point, we will adjust our schedule and focus to accommodate the spirit of the times. This means that the romanticism “Kitchen Talks” will end. Our local Section work, however, will continue, I might expect and certainly hope. It really depends on the good will and enthusiasm of those friends and members who participate. I will look into using my Zoom account, and I will follow up soon with some suggestions on possible next steps, and I will suggest a new focus for our research — one that may help us meet the challenges of our time.

Meeting Summary

Last night, however, I introduced Plato and Neoplatonism. We discussed Blake’s lifelong relationship to the western mystery tradition. To situate the discussion, I referred to Rudolf Steiner’s book: Christianity and Occult Mysteries of Antiquity. I recommended that participants familiarize themselves again with this book, but in particular with the chapter “Plato as a Mystic,” which begins with these words by Steiner:

“The significance of the Mysteries in the spiritual life of Greece can be seen in Plato.”

“To the Sacred Majesty of Truth”

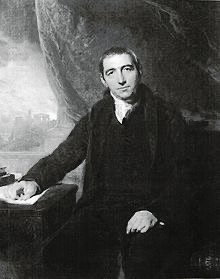

I then introduced a person who has not received attention yet in our discussions: Thomas Taylor. Taylor and Blake were contemporaries and friends. Taylor’s self-appointed mission in life was to reintroduce Platonism and Neoplatonism to England, Europe, and to the world. His writings, translations, lectures, and life activities were quite influential for the romantic poets – not just for Blake, but for Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, and many others. In America, Ralph Waldo Emerson read Taylor enthusiastically. Like Blake and the romantic poets, Emerson found in Taylor’s translations of Platonic and Neoplatonic texts a fountainhead of inspiration that contributed greatly to the Transcendentalist worldview. Yeats, by the way, was another avid reader of Taylor. In the 20th century, the scholar/poet Kathleen Raine (founder of Temenos Academy) took up the banner for Taylor’s cause. I highly recommend Raine’s work on Blake and the Tradition.

Journey’s End… or Beginning?

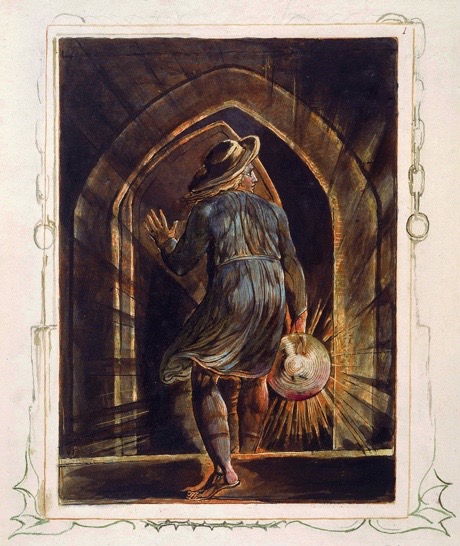

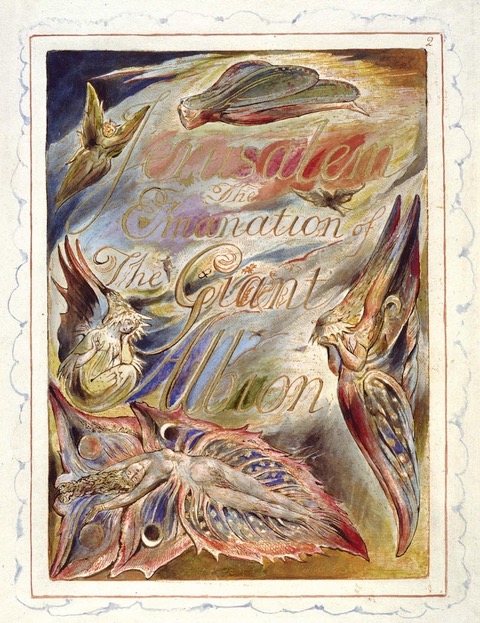

In order to explicate the relationship between Taylor and Blake, and to show some examples of the Platonic wisdom stream in Blake’s artistry, I discussed two of Blake’s paintings: “The Sea of Space and Time” and “The River of Life.” These examples from the visual arts allowed us to spend time in conversation as we reviewed some of Rudolf Steiner’s words about the Perennial Philosophy, so called. By shifting our perspective in this way, we were able to begin to read Romanticism as a continuation of the Enlightenment project rather than as a reaction to the Enlightenment – or, to put it another way: Romanticism as an “Enlightenment of the Enlightenment.” Romanticism is many things to many people, as A.O. Lovejoy famously noted, and a narrowed definition of Romanticism is impossible. But clearly one important aspect to an understanding of Romanticism is an appreciation of Romanticism’s debt to the western mystery tradition, the tradition that finds expression in Plato and his students. Moreover, as we know, Plato was a literary stylist; an early example of a practitioner of the “Beautiful Sciences,” one might say.

We did not have time to go further with this discussion or to weigh the counter-arguments. We will continue the exploration in our later get togethers. As we move toward Shelley, it will be helpful to have Plato and the Neoplatonists on board. And at some point, we should turn attention to the Orphic Mysteries. We already had a start on this with Rilke, but we should look at Greece and the Orphic texts. Also, for those who have been attending the meetings for several years, think back to our discussions of Shakespeare’s play Pericles in which the Platonic worldview is very evident. In this play, Shakespeare pivots to his late style of the romances, and for those who are sensitive to the Tradition, it is clear that Shakespeare uses the Tradition as the initiatory wisdom underlying the drama.

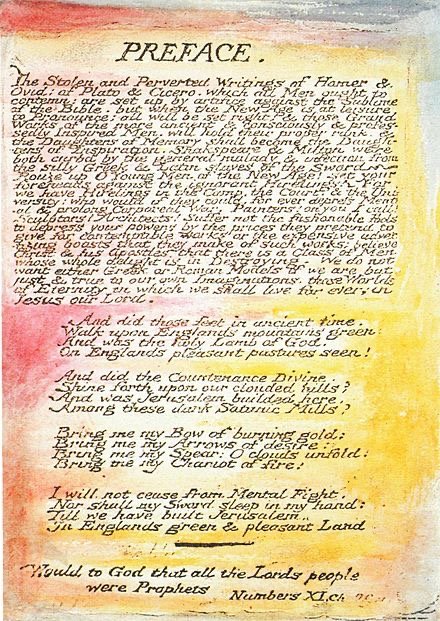

“Would to God that all the Lord’s people were Prophets”

As the evening drew to a close, I posed the question: what does the Section of Literary Arts and Humanities bring to the table that is unique to our perspective on literature? What do we offer uniquely as a methodology? And I offered another quote from Steiner – this one from a lecture we are taking up this season at the Faust Branch: “Raphael’s Mission in the Light of Anthroposophy (GA 62, Lecture 9, January 30, 1913, Berlin). I have the impression that Blake would have enjoyed it, maybe.

“However, from the standpoint of spiritual science we have to see the human being as having an existence over and above the lower kingdoms of nature. With the human being we have, in spiritual scientific terms, what is much older than all the creatures that stand in relative proximity to him in the kingdoms of nature. For spiritual science the human being existed before the animal, the plant or even the mineral kingdom came into being. We look back into far distant perspectives of time in which what is now our innermost nature was already there, only later to unite itself with the kingdoms that stand below the human being. Thus, we see the essential being of Man descend, that in truth can only be comprehended in raising ourselves to the supersensible, to what is pre-earthly. By means of spiritual science we come to recognize that no adequate conception of the human being is to be gained from forces connected only with the earth. We must raise ourselves to super-terrestrial regions to see the approach of the human being.”

“. . . when a man sees beauty in this world and has a remembrance of true beauty, he begins to grow wings.”

— Plato“Classicism is health, romanticisim is sickness.”

— Goethe