Here is a summary of the recent Section for Literary Arts & Humanities meeting of the local group in Fair Oaks, CA. This meeting occurred on February 8, 2020 via Zoom.

Meeting Summary

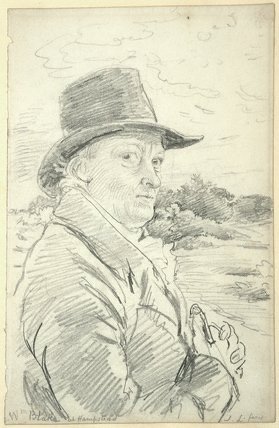

At the “kitchen talk” on British Romanticism yesterday February 8, I presented William Blake.

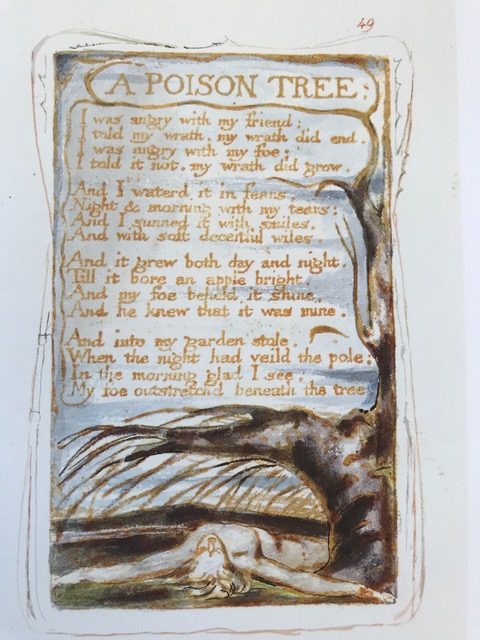

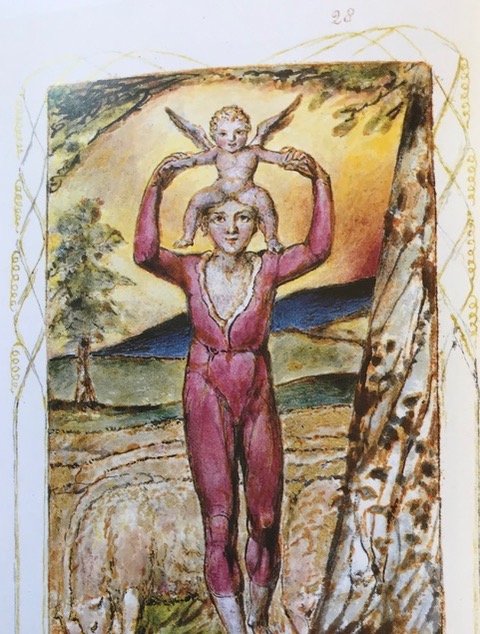

Blake is a challenging poet, as I have noted in previous emails. One of the worst ways to encounter Blake is to ignore his artwork. If we only read his poems, we do just the sort of thing that Blake railed against his entire life: we view him through a narrow chink. Blake, as you know, was an artist. Such training as he had during his lifetime was a training and apprenticeship in the Visual Arts. He taught himself to write poetry by doing what good poets do: read and hear the poetry of other poets. He had no official schooling in the Literary Arts. After Blake’s brother Robert died in 1787, Blake launched himself on a lifelong project that united poetry and the visual arts. Blake’s illuminated books – hand crafted art objects of tremendous aura (in the sense that Walter Benjamin uses the word “aura” as an art-critical term — see Walter Benjamin’s essay: “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”) are splendid representations of the partnership of the visual arts and literary arts. We have other representations of this partnership – such as Michelangelo (a poet in addition to his activity as a painter and sculptor) and J.R.R. Tolkien, etc. – but Blake is unique.

For this reason, I centered the evening on Blake’s artwork. I photographed and displayed many representative works of art from Blake’s illuminated books, and as we contemplated the pictures I discussed the contribution and context of Blake as a poet. Whenever in the past I presented Blake at the university, I always felt that I was cheating the students because they had little or no experience of Blake’s art. (Let alone Blake’s understanding of initiatory science!) But, if we read Blake in the manner in which he wanted to be read, we must appreciate his artwork with his poetry.

We might wish to place Blake in the tradition of meditants who created illuminated manuscripts, some would argue. Just as the great masterpieces of manuscript illumination such as the Book of Kells aspire to enlighten our spiritual understanding, Blake saw the task of “Poetic Genius” to be a task of enlightenment — a secular enlightenment, perhaps. That is to say: an enlightenment for those who are embodied authentically in this world of wondrous Being. Blake is Christic, but not Christian, as I said previously. And this distinction (“Christic but not Christian”) is a challenging concept for some readers. It’s one reason that Blake is difficult to teach to students who have no background in something such as Anthroposophy. However, I don’t think members and friends of the Section feel much at sea. Most of us are well read in matters of esoteric Christianity. Blake, too, was at home in this world of the renewed mysteries. For this reason, he despised institutional religion and most religious institutions, for he thought these churchly factories were hypocritical – more interested in power strategies that hobble the human spirit than they were interested to proclaim a gospel of liberation. You see how well Blake fits in with the romantic challenge for renewal of self and society, eh? Blake believed in the human being as Anthropos. He read the universe as Anthropocosmos. “Christ” was for Blake the great representative of the Human Being. Christ brought the promise of a spiritualized earth (called “Jersusalem” in Blake’s vocabulary), as well as the promise of “Poetic Genius”: that is to say: the promise of a free, ethical, creative human being, whose eyes to the Holy are opened by power and virtue of the Imagination.

Blake is a challenging poet, as I have noted in previous emails. One of the worst ways to encounter Blake is to ignore his artwork. If we only read his poems, we do just the sort of thing that Blake railed against his entire life: we view him through a narrow chink. Blake, as you know, was an artist. Such training as he had during his lifetime was a training and apprenticeship in the Visual Arts. He taught himself to write poetry by doing what good poets do: read and hear the poetry of other poets. He had no official schooling in the Literary Arts. After Blake’s brother Robert died in 1787, Blake launched himself on a lifelong project that united poetry and the visual arts. Blake’s illuminated books – hand crafted art objects of tremendous aura (in the sense that Walter Benjamin uses the word “aura” as an art-critical term — see Walter Benjamin’s essay: “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”) are splendid representations of the partnership of the visual arts and literary arts. We have other representations of this partnership – such as Michelangelo (a poet in addition to his activity as a painter and sculptor) and J.R.R. Tolkien, etc. – but Blake is unique.

For this reason, I centered the evening on Blake’s artwork. I photographed and displayed many representative works of art from Blake’s illuminated books, and as we contemplated the pictures I discussed the contribution and context of Blake as a poet. Whenever in the past I presented Blake at the university, I always felt that I was cheating the students because they had little or no experience of Blake’s art. (Let alone Blake’s understanding of initiatory science!) But, if we read Blake in the manner in which he wanted to be read, we must appreciate his artwork with his poetry.

We might wish to place Blake in the tradition of meditants who created illuminated manuscripts, some would argue. Just as the great masterpieces of manuscript illumination such as the Book of Kells aspire to enlighten our spiritual understanding, Blake saw the task of “Poetic Genius” to be a task of enlightenment — a secular enlightenment, perhaps. That is to say: an enlightenment for those who are embodied authentically in this world of wondrous Being. Blake is Christic, but not Christian, as I said previously. And this distinction (“Christic but not Christian”) is a challenging concept for some readers. It’s one reason that Blake is difficult to teach to students who have no background in something such as Anthroposophy. However, I don’t think members and friends of the Section feel much at sea. Most of us are well read in matters of esoteric Christianity. Blake, too, was at home in this world of the renewed mysteries. For this reason, he despised institutional religion and most religious institutions, for he thought these churchly factories were hypocritical – more interested in power strategies that hobble the human spirit than they were interested to proclaim a gospel of liberation. You see how well Blake fits in with the romantic challenge for renewal of self and society, eh? Blake believed in the human being as Anthropos. He read the universe as Anthropocosmos. “Christ” was for Blake the great representative of the Human Being. Christ brought the promise of a spiritualized earth (called “Jersusalem” in Blake’s vocabulary), as well as the promise of “Poetic Genius”: that is to say: the promise of a free, ethical, creative human being, whose eyes to the Holy are opened by power and virtue of the Imagination.

Clearly, this makes Blake a very challenging poet and artist. He did not make life easy for himself, to be sure! As he liked to style it: his was the voice of one crying in the wilderness (see “All Religions Are One.”) His star began its ascendency with the Age of Light, and it has grown brighter ever since. While Blake’s contemporaries may not have had the background or basic faculties to appreciate his work, many of us who are his inheritors do. The rediscovery of Blake in early to mid 20th century is an exciting story in itself. It is another exciting chapter in the history of romanticism come of age.

We will continue with Blake at the next kitchen talk, probably – although we really should turn our attention soon to Blake’s friend and co-creator, Mary Wollstonecraft – a woman just as annoying, enlightening, and unsettling as her colleague William. What a Promethean pair! Not to mention Mary’s son-in-law, Percy! And do I catch a glimpse of Byron cantering about on the greensward near the hawthorne?

For educational purposes, I put a photo sampling of some artwork from last night’s presentation in a shared Google drive, in case you want to see it. Click here to view the presentation.

We will continue with Blake at the next kitchen talk, probably – although we really should turn our attention soon to Blake’s friend and co-creator, Mary Wollstonecraft – a woman just as annoying, enlightening, and unsettling as her colleague William. What a Promethean pair! Not to mention Mary’s son-in-law, Percy! And do I catch a glimpse of Byron cantering about on the greensward near the hawthorne?

For educational purposes, I put a photo sampling of some artwork from last night’s presentation in a shared Google drive, in case you want to see it. Click here to view the presentation.

Video Performance of Blake’s Poetry

For those who missed the recent New Moon Salon in December, Patricia and I plan to make a performance video of the two Blake poems that were premiered at that salon. These are poems set to music composed by me for classical guitar and singer. Patricia sings; I play the guitar. The two poems are “Tyger Tyger” and “The Divine Image.”

The Garden of Love

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And Thou shalt not. writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys & desires.

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And Thou shalt not. writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys & desires.

— Wm. Blake

“Do not be afraid of the confusion outside you, rather of the confusion inside you.”— Friedrich Schiller