Here is a summary of the recent weekly Section for Literary Arts & Humanities meeting of the local group in Fair Oaks, CA. This meeting occurred on September 5, 2020 via Zoom. At this meeting, we continued our consideration of Novalis.

Meeting Summary

Last night Alice gave us a presentation on Rudolf Steiner’s eurythmy forms that Rudolf Steiner created by request for the dedicatory poem that stands at the beginning of the novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen by Novalis. These are the only forms that Steiner created for a Novalis poem, Alice told us.

I must say, Alice transcended the limitations of Zoom to engage us all artistically and imaginatively in her presentation. Alice guided us through the forms and explained how a eurythmist would approach them and realize them on stage — noting colors, vowels, and consonants, and meter. The interrelationship of the four eurythmists who would move these forms came alive from Alice’s illustrations and presentation. Karen volunteered to read the poem in the original German. As Karen read the lines, Alice guided us through the forms. I for one certainly felt a heightened appreciation for the music of the spoken poetry as it revealed itself in movement.

While it might seem from a certain abstract “scribe” point of view to be counterintuitive to present eurythmy in a Zoom meeting, the imagination remains forever free. Alice’s heartfelt and experience-based observations helped to ground us even more completely in our work with Novalis. She also commented on the sonnet structure of the Dedication poem — noting that Novalis used a Petrarchan rather than a Shakespearean sonnet structure. This in itself would have made an interesting evening’s discussion — to explore why Novalis chose the sonnet form generally and the Petrarchan sonnet in particular for the dedicatory poem. With the advent of romanticism, the sonnet assumes a certain renewed luster, as some have noted. We saw this with Wordsworth and Keats, for example.

Ludwig Tieck

Alice also drew our attention again to Ludwig Tieck and to Tieck’s very important “Notes” concerning the novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen. She pointed out that the incomplete second part of the novel is in fact quite encompassing in scope. Although Novalis did not live long enough to realize the complete architecture of his intended design, we can nevertheless feel the grandeur of conception in the few pages that he wrote — and Tieck’s commentary and observations add a great wealth of detail to our appreciation. I hope that in future meetings we will be able to spend some time with Ludwig Tieck — the tales and dramas, perhaps. If you aren’t familiar with Tieck’s fiction, a good place to start might be The Blond Eckbert or The Rune Mountain. If memory serves me, I believe we discussed The Rune Mountain briefly several meetings ago, in concert with chapter five of Heinrich von Ofterdingen — the chapter in which young Heinrich is initiated into the mysteries of subsurface worlds: caves and mines.

To follow that reference to Ludwig Tieck a bit further, we started the meeting with a poem by Novalis — a poem which, according to Tieck’s remembrances of his intimate friendship with Novalis, are lines that capture and summarize the “interior spirit” of all the poet’s works. I’ll share the poem at the end of this summary.

Jorinda and Joringel: A Performance Video

After Alice’s splendid presentation, we shared an artistic moment. Margit, Marion, and I — as part of our Section work with Novalis over the past several months — have started to produce performance videos of “fairy tales” as a means to add an artistic dimension to our Section work and as a way for our Section work to reach potentially a wider audience via Vimeo and YouTube. We felt encouraged to take this step after reading Novalis and after hearing what Novalis had to say about “fairy tales.” In German, the word is Märchen — but there is no equivalent term in English, some might argue.

It is curious that when I mention to friends outside our Section group that I work on “fairy tales” and make videos of them, they all think that I am doing something for children. This makes me smile! While some fairy tales are clearly of a didactic nature and are meant to instill “proper” behavioral values — some “fairy tales” contain very deep wisdom, such as we might even wish to call “initiatory wisdom.” Some are in fact quite transgressive, vis a vis “proper” behavioral norms. Friends and members of the Section certainly know this, of course — but as I said, many persons that I meet round and about seldom suspect that these “tales for children” are initiatory narratives of threshold experiences — tales of transformation — true “Mysteries” — alchemical gems. They are indeed “open secrets,” as are all deep truths. At any rate, that is how Novalis understood them — and Tieck as well, for that matter. Kafka, too?

Margit and Marion and I started our work with the tale Hyacinth and Rosebud which is found in The Apprentices of Sais. Our recent effort, shared last night, was the tale Jorinda and Joringel. We chose this tale for personal reasons (we each had separate personal connections to the tale), but we also chose it because of its clear resonances with the “blue flower,”

Here is the video of Jorinda and Joringel.

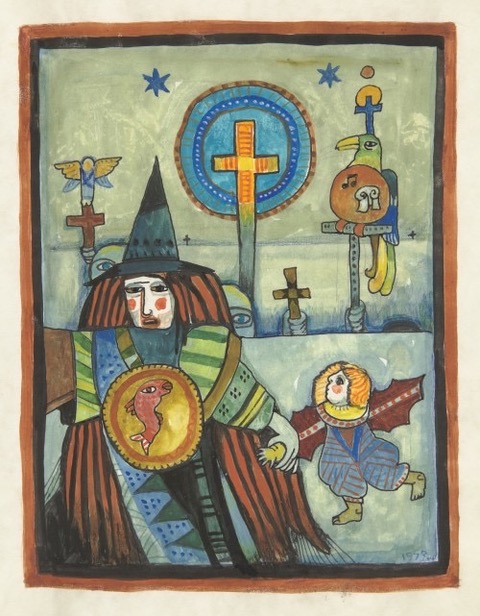

Marylou Reifsnyder. From The Picture Book of Days; Witch with Batchild. Harwood Museum of Art

Narcissus and Goldmund

Next week we will start our journey with Hermann Hesse — specifically with Hesse’s novel Narcissus and Goldmund. It doesn’t matter what translation you decide to use. When I taught this book many years ago, I used the Bantam edition, because it was cheap.

While at first it may appear that this novel of the Middle Ages is a radical and perhaps puzzling departure from Novalis, those who know Hesse will recognize the affinities that Hesse has with Novalis. I think we will find more “Novalis” in the novel than one might first expect. Hesse’s book has many similarities to Heinrich von Ofterdingen, for example (an interesting thesis topic, maybe, eh?) — and one might even say that Hesse has structured his novel as a fairy tale of sorts — following Novalis. The prose is crystal clear in German — the contrasting characters of the book illuminate dichotomous themes that one might immediately identify from Novalis, perhaps.

The book was first published in 1930. Hesse’s return to the idealized setting of the Middle Ages is an interesting choice, given the historical pressures at that time. Our present moment is equally fraught, one might argue. Why did Hesse choose such a narrative mannerism? Why did Novalis, living at the Time of Revolution, recommend us to the “fairy tale?”

Jump in and start reading! Next week we will look at the beginning of the book and try to set the narrative into context and perspective a little bit. But don’t lose sight of the late eighteenth century and our friends and patrons thereabouts!