Clifford Venho is a poet, eurythmist, and translator. He currently works as managing editor at SteinerBooks and teaches literature at the School for Eurythmy in Spring Valley, NY. Cliff is a member of the collegium of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities. Several of his presentations and lectures are on this website.

Toward a Poetics of Wholeness

by Clifford Venho

“Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence; the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related; the eternal ONE. And this deep power in which we exist, and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficing and perfect in every hour, but the act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one. We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are the shining parts, is the soul.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

“The artist transforms the individual element, bestowing on it a universal character; he changes it from something that is merely happenstance into a necessity, from something earthly into something divine. The task of the artist is not to give the idea a physical appearance but rather to allow reality to appear in its ideal light. Significant is not the what, which is derived from reality, but the how, which is the province of the creative power of genius.”

—Rudolf Steiner (from a notebook; GA 271)

We live in rhythm, surrounded by rhythm in nature. The iris on my windowsill unfolds the most delicate petals—tiger stripes inside, five petals of changing shades of purple, the nectar coating the heart of the blossom, fragrant and sweet. When I return to it later in the day, the flower has already withered, shriveled up, grown brown and brittle. Its rhythm is short, just a day—but what beauty in a day! And then, within a few days, another iris has blossomed, and the cycle repeats itself.

As soon as you move from what to how, you leave the static world of objects and enter the unfolding stream of process. The how of a thing needs no why. “The rose is without a ‘why.’ It blooms because it blooms” (Angelus Silesius). We are so concerned with creating hypotheses and theories that we forget to observe. Instead of listening, we talk. We have ears but cannot hear. We are like the crowd of tourists in a museum who go from artwork to artwork, never really taking anything in, too busy taking pictures on smartphones. No time for reflection, inner deepening, inquiry—we’re too distracted to let the world impress its own truth on us.

There is a wonderful anecdote written by Michael Bauer, a friend and biographer of the poet and (according to Rudolf Steiner himself) true representative of anthroposophy Christian Morgenstern. Bauer describes how he and Morgenstern, who had a deep and sensitive nature, would take walks in the garden of a villa in northern Italy. Bauer, who was a keen student of botany, wanted to compare the flora of this region with that of his native Germany, and often found himself looking up the names of the various plant species he saw. He noticed that Morgenstern approached the plants completely differently:

Morgenstern was not at all concerned with comparison and naming. He observed inwardly each form purely for itself. It appears he was worried that names, like so much human noise, would frighten the soul of the delicate nature beings. And he looked at a landscape in the same way. . . . It was for this reason that the sight of a simple valley with a stream flowing through it, or a pair of trees against the horizon, could shake him to the core.

—Michael Bauer

This inner activity of letting the world make its impression on us is vital to the artistic path of knowledge. It is not a knowledge of the head alone, but a deep knowledge of the ground of things. Out of this inner deepening, Morgenstern was able to write the following poem:

I have seen man in his deepest form,

I know the world to its very core.I know that love, love is its deepest meaning,

and that I’m here ever more to love all beings.I open my arms out wide, as He has done,

I want, like Him, to embrace the world as One.—Christian Morgenstern

With our intellect, we dissect, categorize, specify, differentiate. But if we can approach the world with another faculty, that of imagination—not in the sense of idle fancy but in Coleridge’s comprehensive meaning—then the secrets of the world begin to reveal themselves to us. Coleridge writes in his Biographia Literaria:

The Imagination then I consider either as primary, or secondary. The primary Imagination I hold to be the living Power and prime Agent of all human Perception, and as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM. The secondary I consider as an echo of the former, co-existing with the conscious will, yet still as identical with the primary in the kind of its agency, and differing only in degree, and in the mode of its operation. It dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to re-create; or where this process is rendered impossible, yet still at all events it struggles to idealize and to unify. It is essentially vital, even as all objects (as objects) are essentially fixed and dead. (167)

—S.T. Coleridge

Coleridge contrasts this vital activity of imagination with what he terms “fancy”:

Fancy, on the contrary, has no other counters to play with, but fixities and definites. The Fancy is indeed no other than a mode of Memory emancipated from the order of time and space; while it is blended with, and modified by that empirical phenomenon of the will, which we express by the word Choice. But equally with the ordinary memory the Fancy must receive all its materials ready made from the law of association. (167)

—S.T. Coleridge

Thus, for Coleridge, imagination is not a flight of “fancy” but the inner activity by which we gain a deeper insight into the connections between things, by which we begin to fathom the wholeness of the world. Fancy, on the other hand, gives us fixed images and tends toward differentiation, toward the parts rather than the whole.

The work of imagination is vital for the poet—whom Coleridge speaks of as being nearly synonymous with poetry itself. After all, it is the poetic genius that gives birth to poetry, and this genius wields imagination as an essential instrument of creation:

The poet, described in ideal perfection, brings the whole soul of man into activity, with the subordination of its faculties to each other according to their relative worth and dignity. He diffuses a tone and spirit of unity, that blends, and (as it were) fuses, each into each, by that synthetic and magical power, to which I would exclusively appropriate the name of imagination. (173–74)

—S.T. Coleridge

In this connection, it is interesting to look at how Coleridge, following Kant’s lead, distinguishes between understanding (Verstand) and reason (Vernunft). In The Friend, he writes that in understanding, “we think of ourselves as separated beings, and place nature in antithesis to the mind, as object to subject, thing to thought, death to life” (I, 520-521). He describes reason, on the other hand, as “that intuition of things which arises when we possess ourselves, as one with the whole, which is substantial knowledge.” Rudolf Steiner, in his book Goethe’s Theory of Knowledge, develops this line of thought further:

Reason does not presuppose a certain unity but the empty form of unification. It is the ability to draw the harmony up into the light as long as it is present in the object itself. In reason, the concepts join themselves together into ideas. Reason (Vernunft) brings into view the higher unity of the concepts of the understanding (Verstand), which the understanding indeed has in its formations but is not able to see. (88)

—Rudolf Steiner

Steiner refutes Kant’s abstract “thing-in-itself.” For Steiner, ideas belong to a unified ideal world of reality perceived through the faculty of reason, which inherently bears the attribute of “emptiness.”

Coleridge’s, and Steiner’s, view of the faculty of reason in the sciences is connected with the faculty of imagination in the arts. As we saw in his Biographia Literaria, for Coleridge, imagination is a delving into the unified wholeness of reality, a leap from the individual, discrete unit back to the whole from which it emerges and to which it belongs.

Thus, we can begin to understand how science and poetry (or art more broadly) are related to each other as two sides of the same coin. Goethe characterizes the relationship of science and art:

I think science might be called the knowledge of the general or abstract knowledge; art, on the other hand, would be science applied to action; science would be the reason and art its mechanism; therefore, one might also call it practical science. And thus, finally, science would be the theorem and art the problem. (Maxims and Reflections)

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

In this view, science is the path by which we go from the given content of our experience to the ideas or laws that stand behind those experiences. Art goes in the opposite direction. It raises the experience into the realm of the idea so that the idea is not “behind” the experience but embodied within it. As Steiner puts it in the concluding chapter of Goethe’s Theory of Knowledge:

The infinite, which science seeks in the finite and endeavors to represent in the idea, is imprinted by art upon a material taken from the sense world. What appears in science as idea is, in art, image. It is the same infinite that is the object both of science and of art; it is only that it appears differently in the one than in the other. (156)

—Rudolf Steiner

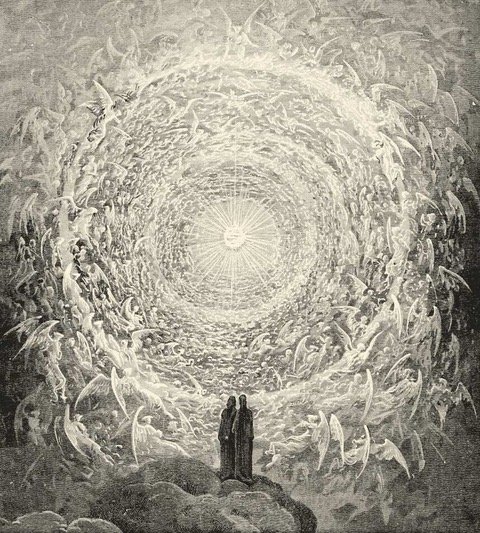

Art, therefore, is neither a purely subjective expression nor a copying of the natural world—it is the revelation of the idea within the sense world, a sensory experience clothed in spiritual raiment. Imagination is the central faculty by which this wholeness of the world, and its infinite creative possibilities, is made available to the artist.

One of the fundamental hurdles to a real experience of this form of imagination is the ingrained notion of a subject-object divide. Subject and object are concepts grasped by our intellect (or understanding, in Coleridge’s sense); they are not fundamental in themselves. The act of knowing is an emersion in the wholeness of the world, in its indivisible unity—although it appears at first to be divided. We are given disparate experiences—a perception of a shape, a color, a movement. These perceptions appear at first to be unconnected, until we discover their concepts with our intellect—tree, stone, grass, etc.—and arrive at the unity of the world of ideas through the “empty striving” of our reason.

This subject-object divide is useful for measuring and quantifying the world we perceive. By our very nature and constitution—more than any other creature on Earth—we experience ourselves as separate from the world, as a subject surrounded by objects. But this duality is not a fundamental reality. It is a result of our makeup.

The English poet Kathleen Raine writes about William Blake’s battle with the subject-object divide, which leads inexorably to the worldview of materialism:

To Blake the radical error of Western civilization lies in the separation…between mind and its object, nature. Blake’s inspired but uncomprehended message was neither more nor less than to declare and demonstrate the disastrous human consequences of this separation, and to call for a restoration of the original unity of being in which outer and inner worlds are one. (Golgonooza, City of Imagination)

—Kathleen Raine

Raine describes her own experience of the overcoming of this divide—she was once looking at a hyacinth in all its mysterious detail, when “abruptly I found that I was no longer looking at it, but was it.” We limit ourselves through the unquestioned epistemological view that there is a fundamental division between subject and object. That is not to say we should discard the experience of our own individual consciousness of self—rather, we must take this experience and move with it consciously toward a re-union with the whole, of which we are part and parcel:

“. . . in your own Bosom you bear your Heaven and Earth & all you behold: tho’ it appears Without, it is Within, in your Imagination”

—William Blake

“When nature begins to disclose her open secret, we experience an irresistible yearning for its worthiest interpreter—art” (Maxims and Reflections).

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

This brings us to the question of form and content in nature and art. In science, the form of something (a tree, let’s say) leads us to its content (the laws that govern its growth). The individual tree is illustrative of the law that applies universally. In art, we can’t speak in the same way of an artwork as pointing to something outside of itself. Archibald MacLeish expressed this eloquently in his famous poem “Ars Poetica”: “A poem should not mean but be.” Thus, the real (form) and ideal (content) of art belong to a complete unity.

This real-ideal nature of art applies in a special way to poetry. In poetry, we are working closely with thoughts, but if we were simply to express thoughts, as I’m doing right now, the result would be an essay, not a poem. The element of its appearance or form—structure, sonics, rhythm, etc.—has to be united completely with the ideal content of the poem, with its idea. The more this can happen, the more effective the poem is and the more we feel it to be true. We perceive form and meaning in “an instant of time.” This is Pound’s definition of the poetic image. It is this moment of experience in which we sense the wholeness of things, in which the words, thoughts, images, emotions, sounds come together in an indivisible unity, in which the inner breathes with the outer and the outer with the inner, that we can locate the essence of poetry, and art in general.

Goethe speaks of this relationship between inner and outer in terms of a rhythm, “a continual systole and diastole, an inspiration and an expiration of the living soul” (Maxims). This living exchange between inner and outer, by which the two become one, lies at the heart of the poetics of wholeness.

2.7.23