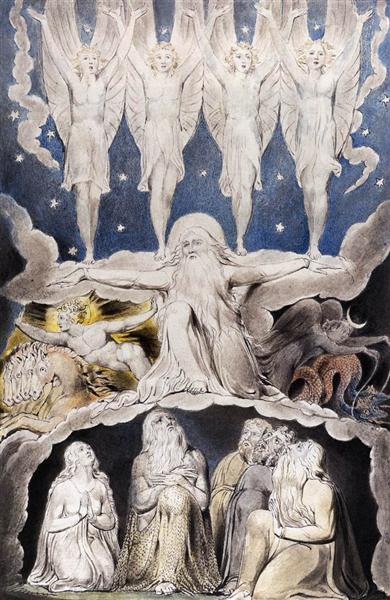

“When the Morning Stars Sang Together” by William Blake

Here is a summary of the recent Section for Literary Arts & Humanities meeting of the local group in Fair Oaks, CA. This meeting occurred on February 27, 2021 via Zoom.

“At a Glance . . .”

- Eurythmist and poet / translator Clifford Venho joined us from Hawthorne Valley for a special evening in which Cliff discussed his translation of Hymns to the Night by Novalis

- The entire evening was devoted to Novalis. It was a full moon, and it was also Rudolf Steiner’s birthday! (a disputed date)

- See our Books and Essays page for forthcoming information about obtaining Cliff’s chapbook edition of Hymns to the Night by Novalis

- Upcoming: Terry Hipolito has agreed to share with us a presentation on March 20 and Brian Gray has agreed to visit on May 1. We will not have meetings during Eastertide; no weekly meeting on March 27 and April 3

“Tell me more . . .”

“The Holy, Unspeakable, Mysterious Night . . .”

The challenge and radical re-visioning of human experience, such as we read in Hymns to the Night by Novalis — often is occluded for English-speaking readers by haze of well-intentioned translation. We are very fortunate that poet and eurythmist Clifford Venho has done a freshly voiced recent translation of Hymns to the Night — a translation that is lucid, poetic, and true to the spirit and music of the original text.

At our meeting last night, Cliff shared something of his journey with Novalis and discussed the events that led him to translate Hymns to the Night. Cliff also read from his translated version of the poem. Following this, he answered questions and participated in a general conversation concerning Novalis. Cliff touched upon the problems of translation and upon many themes that we have found in Novalis’ poetry and prose writings over the past year of our close work. Prominent among those themes is a topic that we discussed several times: the Lumen Naturae — the “light of nature” or “the light that shines in darkness.” (See April 11, 2020 summary and other Meeting Summaries on the local website.)

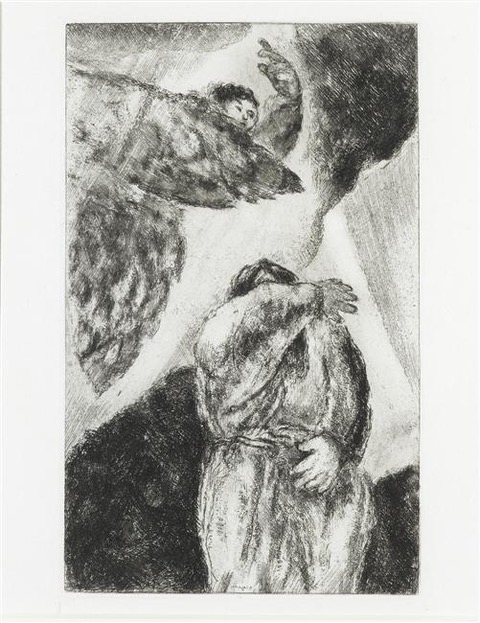

“The Lord Appears to Elijah at the Entrance to the Cave in which He Took Refuge” by Marc Chagall

“Must Morning Always Come?”

Our journey with Novalis has led us repeatedly to caves and dark enclosures. Unfortunately for readers in the late-romantic nineteenth century and modernist twentieth century, this emphasis on Darkness and the Unspeakable led to some misreadings of Novalis. A veil of late-romantic incense wafted thickly about the few English translations of Novalis that were available. Novalis became a brand name for romantic “Sehnsucht” — the noble poet of the blue flower who longed for death and sweetheart and mother — a poet closely associated with love and loss, despair and darkness, and — worse yet! — some vague mystical Pan-piped longing to transcend this “vale of tears” and escape with the lost boys to Never Never Land. Recent scholarship has done much to ground and humanize Novalis and to replace the idealized heroic bust gathering dust in over-heated sitting rooms with representations more in context with the spirit of the time in which Novalis lived. That time, by the way, was target-center within the years of the late eighteenth century that we are studying. These are years that Rudolf Steiner repeatedly recommended to our close attention. Rudolf Steiner did so in regard to that period’s significance for anthroposophy, and of course in regard to the period’s significance for the School of Michael. We are fortunate to find ourselves alive in this twenty-first century in which, thanks to the work of recent scholars and a new generation of translators, the Poet of the Blue Flower can be better read and understood.

Those who turn to the philosophical work of Novalis will be disappointed if they expect here “romantic” illuminations and snappily formulated emotional effusions. Rather, his texts belong to the most difficult of German philosophy.

— Manfred Frank, Einführung in die Frühromantische Ästhetik: Vorlesungen (Suhrkamp, 1989; pg. 248)

“Holy Cave” by Nicholas Roerich

“You have shown me the night that leads to life — and made me truly human.”

But, lest we rush off to another extreme — encouraged by scholarly reappraisal of Novalis as a highly significant philosopher (as indeed he was!) — we should bear in mind that Novalis saw himself as a poet, first and foremost. Have we not heard so often in past meetings that for Novalis the fairy tale is mightier than philosophy? Indeed, some have argued persuasively that with Novalis — as with the poet Rilke, for example — it is the Orphic stream that we encounter — not the Aristotelian or the Platonic. What does this Orphic stream offer? Who was Orpheus? How can the “Unspeakable” be spoken? Is this sort of chatter more late-romantic-cloud-cuckoo-land Lorelei Quatsch? Do we not hear something morbid and contrary to the spirit of social “progress” (Liberté! Égalité! Fraternité!) — contrary indeed, if we mistakenly valorize a misreading of mystic maxims such as “Longing for Death” — this phrase notably the title of the sixth section of Hymns. Novalis, as some have noted, is a hard fellow pin down.

All being, being itself is nothing more than being free — hovering between extremes that must of necessity be united and separated. From this focal point of hovering all reality flows — everything is contained in it — object and subject exist through it, not it through them. I‑ness or productive power of imagination, the hovering — determines, produces the extremes, between which it is hovered — This is a deception, but only in the realm of common understanding. Otherwise it is something thoroughly real, because the cause of it, hovering, is the origin, the mother of all reality, reality itself.

— Novalis (II, 266)

O Pioneers!

We heard in previous meetings that Albert Steffen, following Steiner’s many indications, identified Novalis as a poet of the future — not of “The Future” necessarily, but of a Present-potentized. In this respect, as the cliche has it: the future is now. Whatever other “futures” might exist in social engineering schemes or scientistic fantasies is an imagined Hereafter. The future is now — “the time is at hand!” So runs the challenge in early romantic texts. (The name “Novalis,” as we know, means equivalently “pioneer” — or one who “gets on with it,” to add a Whitmanesque emphasis to the affair.)

Steffen suggested that whereas Dante, for example, brought to poetic expression the completion of a previous civilization — the European Christian Medieval civilization — Novalis anticipates a civilization yet to become, now becoming, once and future. And we have heard in recent meetings how strongly Goethe recommended to us the motto: “Die and Become.” Metamorphosis, transformation, change, chaos, death and rebirth — these, too, are Orphic themes. Perhaps in future meetings we may find time to go deeper into this darkness, accompanied by “Virgils” such as Novalis and perhaps even a Rilke or two and others of that good company of friends. The time is a hand!

“Mourning for the Youth” by Hermann Linde

Christian Morgenstern . . .

Cliff has agree to join us again for another literary evening in which he will present his work and his present journey with poet Christian Morgenstern. I look forward very much to that coming event! Watch this space for a date and time. Last week, Mozart and Ingmar Bergman joined our little community of interest. This week, once again, Novalis — and soon, Morgenstern, a person whose significance to Rudolf Steiner might become for us a topic of keen interest. Alas, we remain in the language world of the German. (Doh! If only Rudolf Steiner had been born in Brooklyn or San Dimas!) But with translations such as Cliff’s close in hand, I’m sure we will find secure passage across the Bridge.

“Everywhere the grain stood ripe and the hot afternoon was full of the smell of the ripe wheat, like the smell of bread baking in an oven. The breath of the wheat and the sweet clover passed him like pleasant things in a dream.”

— Willa Cather, O Pioneers!

“Friends, the soil is poor. We must scatter abundant seed to assure even a middling harvest.”

— Novalis, Blüthenstaub“Eve! Magdalene!

or Mary, you?”

— Hart Crane, The Bridge