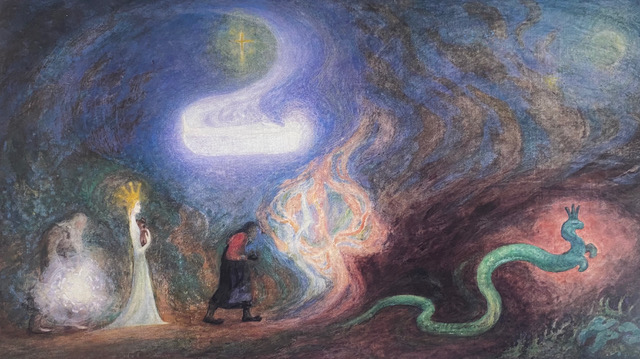

“The Procession to the Bridge” by Hermann Linde

Here is a summary of the recent Section for Literary Arts & Humanities meeting of the local group in Fair Oaks, CA. This meeting occurred on February 13, 2021 via Zoom.

“At a Glance . . .”

- On February 13 we continued our work on The Fairy Tale. We began our evening with a reading of the ferryman / will-o-the-wisps encounter

- For the purposes of education and scholarly citation, we then reviewed all the paintings in the book Imagination by Hermann Linde, published by Walter Keller Press, Dornach, 1988

- We began to consider the relationship of The Fairy Tale to The Portal of Initiation, The Metamorphosis of Plants, and The Magic Flute

- We contemplated Rudolf Steiner’s remark from a 1916 lecture that “spiritual science is matured Goetheanism” (Karma of Vocation)

- Our next meetings will continue in this direction as we deepen our understanding of early romanticism and its relationship to anthroposophy and (post)modernity

“Tell me more . . .”

“Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön”

Opera buffs will recall this exclamation of delight and insight (“This picture is enchantingly beautiful”) as the beginning words to the aria sung by Prince Tamino in the early scenes of Mozart’s Magic Flute — a theatrical sensation that premiered Michaelmas 1791. The “three ladies” have just presented Tamino with a picture of Pamina. This follows their rescue of the Prince from the monstrous serpent. To paraphrase: “Ah,” he exclaims — “fled from me is all fear and terror! This revelation of aesthetic beauty has a magical power to enchant. My will is fired to deeds of love and freedom and spirit insight.”

“In the midst of the awful realm of force, and in the midst of the divine realm of law, the aesthetic impulse to form constructs unnoticed a third happy realm of play and of appearance in which the fetters of all circumstance are taken from man, releasing him from everything that could be called either moral or physical constraint.”

— Friedrich Schiller, On the Aesthetic Education of the Human Being, Letter 27

“A happy realm of play and of appearance . . . “

Goethe was so taken with Mozart’s “mysterious” masterpiece The Magic Flute that he felt fired to write a sequel. In 1795, during the time in which he contemplated and wrote The Fairy Tale, he also was at work on a libretto that he titled The Magic Flute, Part 2 in which Goethe continued Schikaneder’s initiation drama and brought the tale to a new conclusion. Mozart’s opera deeply inspired Goethe, obviously — might we perhaps speculate that Mozart, who died in 1791, might have set a tone for Goethe’s imagination during some dreamtime rendezvous around the earthly year 1795? And while Goethe never succeeded in finding a composer to set his libretto to music, he continued his search for such a maestro for twenty years. (Perhaps, ironically, Goethe should have heeded the insight of Novalis, that Goethe’s “Fairy Tale” of 1795 was in fact “narrated opera.”)

“Göthes Märchen ist eine erzählte Oper.”

— Novalis, Logologische Fragmente

“The Temple on the Bridge” by Hermann Linde

“Beauty alone makes the whole world happy . . .”

Although the signpost for our meeting location last night told us we were on the march to Schiller’s Weimar — “Aesthetic State, 500 KM / Vorsicht! Räuber!” — we found ourselves in such enchanting river scenery that we lingered to enjoy the harmony of nature and the beauty of flowers which, here in the gold country of Northern California, have begun to blossom.

Plants, by the way, were also much on Goethe’s mind in 1795

Our local group discussed how one might read The Fairy Tale structurally as an imagination of The Metamorphosis of Plants. The linear lines of successive growth and successive motion in the first part of the tale give way to circularity after important deeds of “Renunciation” are performed — deeds such as the sacrifice of the green snake to form a bridge. The puzzling sterility of Lily and Lily’s garden — which sadly lacks ability to flower (ah, the missing artichoke!) — might point in this respect to ideas fundamental to Goethe’s theory of plant growth and metamorphosis — for example, the idea that the determined linearity of branch growth must “renounce” or halt itself to achieve the next stage of sexual maturity in the plant. We shall have to unpack this notion at a later date with the help of Goethean botanists — but for the Time Being, we amused ourselves musically. With melodies of Mozart wafting from the garden hut, we preferred to enjoy blossoms rather than sit through a dry as dust philosophy lecture in some cold hall in Jena with Professor Schiller. His time will come! It is at hand! Those “death forces” of the thinking process, about which Rudolf Steiner cautioned, do need some jazzing, however, one might suspect. Fairy tales and music and paintings are marvelous remedies and counterweights, and they come well-recommended.

“Genuine fairy tales originate from sources lying at greater depths of the human soul than is generally supposed, speaking to us magically out of every epoch of humanity’s development.”

— Rudolf Steiner

And from such recommendation springs: a project!

“Longing for Deliverance (Crisis)” by Hermann Linde

Say What? A Project? Homework? Dang!

We discussed a possible (and optional) hands-on “doing” approach to the subject matter of Goethe’s The Fairy Tale. I suggested that one way to “live into the tale” might be to engage with it artistically. A possible approach, I suggested, might be to take one of the characters or “points of view” in the tale and work with that “point of view” artistically. And I think some of us may decide to do that. It is entirely optional, of course. But why not? (Well, I can think of several reasons “NOT,” but let’s remain sanguine and optimistic.)

How to proceed? Well, one might take the Prince, as Linde did in those twelve pictures that we reviewed last night, and imaginatively represent for oneself in story or poetry or painting or music or what-have-you some personal artistic exploration of that character’s experience and point of view. Or you might prefer the ferryman or the old woman or the pug — as you like it! Label Warning: One thing we certainly do not want to do is allegorize. If I may be so bold: Goethe would have had a fit. He scorned equivalencies of meaning — officiously logging ninety-nine “misrepresentations” of the tale — and no doubt that number has grown greatly since. He cringed at interpretative sleights of hand that made “This mean That” and “There you have It! Solved!” The part of our human nature that loves to line things up mathematically and tautologically (A = B; B = A) and which may seduce us to wrap up a text neatly with some pat interpretation (“it really means THIS!”) — well that sort of literary film flam is no literary art, some might argue — although I suppose it can be amusing for a time.

“You may live from within yourself

When light can shine within your soul.”

— from The Portal of Initiation

“The Golden Temple” by Hermann Linde

Sternflammenden Königin der Nacht!

Behold the stars twinkling above the temple that has risen from the earth under the ferryman’s hut. We will continue with Mozart’s opera and Goethe’s “narrated opera” in future meetings — with appropriate digressions, such as to the Nile river valley and the Sphinx temple complex, as befits the mood and itinerary of an initiatory drama. Those Pyramid Texts deserve a glance, do they not? And speaking of stars — as one wag wonce wagered: if we shot into space a holographic time capsule of Mozart’s operas, some distant benighted galactic vagabonds, having found that time capsule, would discover nothing less that the Human, resplendent in song. At close of the evening, we paused to consider a selection from the Leading Thoughts, a passage that begins:

“It is a deep source of satisfaction to Michael that through man himself he has succeeded in keeping the world of the stars in direct union with the Divine and Spiritual.”

— Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophical Leading Thoughts,

“The Activity of Michael and the Future of Mankind”

Detail from “Mourning for the Youth” by Hermann Linde

The Renunciants

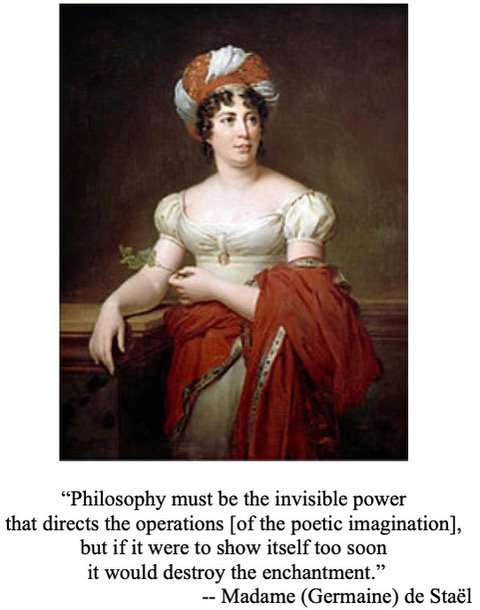

Lastly, we briefly touched on the meaning of the word “Renunciation” (“Entsagung”) in the spiritual sense in which Goethe understood and employed the term. It relates, obviously, to his ideas concerning the metamorphosis of plants and to The Fairy Tale. It was an attitude and gesture of life that came more and more to the fore following this moment in Goethe’s biography that saw the creation of The Fairy Tale. We find renunciation, for example, prominently in the subtitle of another work of literature on which Goethe was laboring at this time in 1795: Wilhelm Meister’s Journeyman Years, or The Renunciants. In future meetings, we may have time, cash, strength, and patience to follow this thread with Meister — but let’s close this summary out for the time being with music and a beautiful portrait and a quote. The quote is from Madame de Staël, a friend of Goethe’s. Perhaps she will join us for a salon!

As for music, here is link to a YouTube video of a performance of the aria from The Magic Flute that we contemplated earlier in this summary. Enjoy!

Link to Mozart aria from The Magic Flute

Scene change. Temple of the Sun.

Sarastro, Tamino and Pamina in priestly apparel, the priests and the three boys appear.SARASTRO

The sun’s rays drive out the night,

destroy the ill-gotten power of the dissemblers!CHORUS

Hail to you on your consecration!

You have penetrated the night,

thanks be given to you,

Osiris, thanks to you, Isis!

Strength has triumphed, rewarding

beauty and wisdom with an everlasting crown!

— Mozart / Schikaneder / Conclusion of The Magic Flute“To romanticize the world is to make us aware of the magic, mystery and wonder of the world; it is to educate the senses to see the ordinary as extraordinary, the familiar as strange, the mundane as sacred, the finite as infinite.”

— Novalis