“Iron Hans in the Cage” by Gordon Browne, 1894

By Bruce Donehower, Ph.D.

This essay originally appeared in 2017 in the Newsletter of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities of the School for Spiritual Science of North America, and prior to that in 2016 it appeared as a shorter version in the Faust Branch community newsletter, edited by Patrick Wakeford-Evans.

_______

Why Can’t Henry Sit Still? / The Moral Challenge of Faust

November 2017

For a few years now, I have been working with friends and members in the Literary Arts and Humanities Section in Fair Oaks on Goethe’s play, Faust, Parts One and Two.

One of the most important questions we have wrestled with is: who is Faust?

To make matters complicated, Faust appears in other works of literature—such as Christopher Marlowe’s Elizabethan tragedy Doctor Faustus (not read by the young Goethe, by the way). Marlowe’s Faust character is based on a medieval individual who inspired folk tales, puppet shows, and chapbooks. Then there is Thomas Mann’s late-life masterpiece Dr. Faustus, a novel about the descent of Germany into fascism. Going back in time, we find a prototype of Faust in Simon Magus (Acts 8:9–24). And then there are all those other Fausts who exist in secondary literature and commentary. When I talk to people about Faust, I frequently discover that the original play by Goethe has not been read by them in its entirety, if at all. I often have the experience that people know the Faust character as an item of “received wisdom” or from essays in secondary literature. They know this rumored Faust better than they know the Faust character who inhabits Goethe’s primary text: the play named Faust.

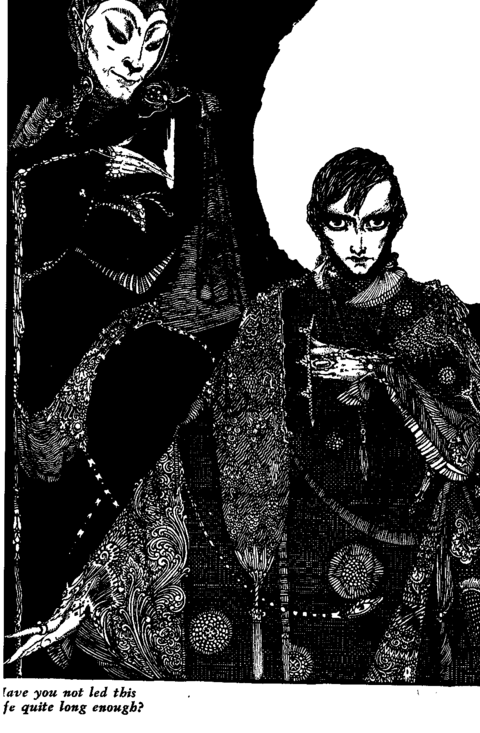

“Faust and Lilith,” by Richard Westall, 1831

Who is Faust?

A good starting point, when we pose this question, is to set aside all the received wisdom about Faust and return to the play, parts one and two. When we do that, what do we discover?

Curiously, for one thing, Faust is extremely restless and unhappy, even suicidal. Already of an age to collect Social Security at the beginning of the play, he is bored, cynical, lonely, soured on life and humanity, narcissistic, and desperately discontent and frustrated. Since he is very intelligent and privileged (a professor) and an alchemist (to boot), one might hope that he had achieved a degree of insight and wisdom and serenity at his advanced age. After all, any of us who trod the path of alchemy and the path of diligent cultivation of spirit and intellect for half a century might hope to have achieved a little enlightenment and equanimity after long decades of tireless toil. But Faust is at odds with himself and life. He rains scorn on others, like a troll. In his opening monologue, he complains famously. He tells us that he is at wit’s end and that he has decided in desperation to turn to magic, the shamanic arts, or else kill himself.

His restless, unhappy attitude summons him a companion—Mephistopheles—who agrees to pull him out of the dumps.

Who is Mephistopheles?

Mephistopheles is often called the devil, but he is not the Devil, or Lucifer or Ahriman for that matter. (We’d need another essay or three to explore the nature of Mr. M, so let’s just stick with Faust.) It’s important to see what sort of relationship Faust and Mephistopheles have.

Faust is no innocent lamb, no wandering Pilgrim whose Progress to Salvation is sidetracked by a fiend from hell. He is an old guy complaining that he needs life, reinvigoration, potency, power, glory, females, and ample scope and money to actualize every male ambition—and damn the consequences. He is obsessed with Helen of Troy, who plays a big role in Part Two—but on the way to Helen he has an affair with a fourteen-year-old virgin that ends very badly for the pure-hearted Christian maiden and for her family—but not for Faust, who skips out on the moral disaster. And after a good night’s sleep, he feels okay.

Faust, the play, has a lot of evil in it, but the evil, time and again, is done by Faust. This catalog of misdeed continues right to the end of the play in Part Two, where (to enhance his enjoyment of his estate) Faust steals the real estate of two old retirees, Philemon and Baucis. Thugs in the employment of Faust brutalize the retirees. The old folks die; Faust steps over the corpses to enjoy his booty.

In short, while Mephistopheles is called the devil, Faust is often the active human devil in the drama. He is not forced to do evil—he decides to commit evil, and he does so as part of his striving personality. In fact, this ambitious zeal to strive and have it “My Way” at any cost is the very characteristic that he needs to cultivate, lest he be damned. Ironically, if at any point, Faust stops and self-reflects mindfully and says “Hey, wait a minute! What am I doing? Haven’t I had enough? I better stop for a moment and self-reflect!” Well, as soon as he says this, Bang! The devil wins! That’s what the pact with the devil is all about. And of course, this devilish dilemma is organized by the Big Boss himself: Lord God Heaven, as we read in the Prologue.

The Young Faust, by Harry Clarke, 1925

Prometheus or Faust?

Admittedly, I’m putting Faust the character in a harsh critical light. But I know that as a youngster before I read the play, I didn’t have a clue what this character Faust was up to. I came to my first reading of the play with a lot of inherited assumptions about the character Faust. I expected Faust to be noble—maybe like a well-meaning Prometheus in the high romantic mode—a spiritual athlete doomed to suffer for his heroic aspirations. But that’s not the character we witness in Goethe’s play.

Faust is an unhappy old man who becomes by magic a restlessly ambitious and often unhappy young man. He makes a lot of other people unhappy and miserable along the way. He can’t sit still and self-reflect. (Goethe, by the way, named his character Heinrich Faust – hence the title of this essay, “Why Can’t Henry Sit Still?”)

Medieval or Modern? / The Challenge of the Consciousness Soul

At this point you probably want to throw rotten tomatoes at me and hiss and boo me off the stage. But before I escape from the platform with a bawdy gigue, let me add that there is, however, an important aspect to this characterization of Faust that we should appreciate, I believe.

Goethe’s Faust lives between two worlds. But the Faust of the original legend (Marlowe’s Faust, for example) is medieval. This medieval Faust lives in only one world—the world of good and evil, black and white, damnation and salvation. Marlowe’s medieval Faust is dragged down to hell in spectacular fashion. Bravo! Not so Goethe’s Faust. Goethe’s Faust is saved!

Saved??

Say what!?

Are you kidding? Is there no god in heaven? Where is justice? God is dead!

Not a bit! For Goethe’s Faust is not medieval, as I said—he is modern through and through. Postmodern? Well, not yet really—because, as Rudolf Steiner tells us, Goethe lived in a benighted time, before the Age of Light, before the end of the Kali Yuga. Goethe could see quite far, but Faust the character can only see far enough, maybe to the end of the nineteenth century.

Faust the character intuits an age of spirit that is approaching, but he can’t get there yet. He has been born too soon. It’s one reason he retreats to classical and pre-classical antiquity. Goethe’s character Faust is not medieval, and this is his curse. He is an aspiring modern human being stuck in a late and crumbling medieval world, a world that only understands binary choices: good / bad, heaven / hell, saved / damned, etc. Indeed, many individuals in our so-called “modern” age are in fact still stuck in a medieval worldview and are living out fantasies of the good old feudal days. Just because the date on your birth certificate says you were born in the twentieth or twenty-first century doesn’t mean that you have learned to live in the Present Age. You might in fact be far more temperamentally suited for the Middle Ages.

This medieval mindset, however, is a mindset that Goethe criticized implicitly and explicitly in his literary and scientific works. His life, as a work of art, is a direct challenge to that backward mindset.

Now, back to Faust. Faust lacks a methodology – a spiritual science, if you will. This is, I would submit, at the heart of his complaint in the famous monologue at the beginning of the play. Because he lacks access to an inner path of spiritual development, he projects his unredeemed soul forces blindly upon the world, seeing evil outside himself rather than inside, and hence, working evil blindly on his environment.

Put in terms of medieval alchemy: Faust does not know how to achieve a true unification of opposites that would allow him to realize the goal of the Great Work. Put in the light of another poet who wrote about these same themes (William Blake): Faust the character does not know how to achieve the Marriage of Heaven and Hell. He cannot sit still. He cannot make that critical inward turn so important for entering upon a path of spiritual science. He longs to do so; he strives toward it; he intuits this path as a possibility. But he cannot actualize such a Great Work in his current incarnation. He is stuck. Thus, when he dies, his soul (or entelechy, as Goethe liked to call it—or his mind stream, to use a more current term) continues its quest, impelled by its karmic imperatives. He is “saved!” He will reincarnate with the “Faust” problem burning inside him, but he will reincarnate in another time and place where it may be possible for him to make the inward turn.

Goethe recognized that in the coming decades and centuries more and more individuals would find themselves playing the role of Fausts: imperfect, morally compromised individuals misled by the genie of personality—personality that knows the price of everything and the value of nothing—personalities longing for a simpler age of good and evil and for superstitious answers to complicated human problems. Each individual Faust thus learning by painful steps, by crimes and hard experience and big mistakes and errors, that the way forward begins with the inward turn.

“Inward goes the secret path. Eternity with its worlds, the past and the future, is in us or nowhere.”

— Novalis“More light!”

— Goethe, allegedly his dying words