An earlier version of this essay appeared in the Yearbook of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities of the School for Spiritual Science (Verlag am Goetheanum: Dornach, 2002) and the Newsletter of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities of the School for Spiritual Science in North America. The present essay has been edited and revised in the light of research and the many experiences that have occurred during the past two decades.

10 Views Toward Grail & Tamalpais:

A Ritual Circumambulation

“Tom’s most well now and got his bullet around his neck on a watch-guard for a watch, and is always seeing what time it is, and so there ain’t nothing more to write about, and I am rotten glad of it, because if I’d a knowed what a trouble it was to make a book I wouldn’t a tackled it, and ain’t a-going to no more. But I reckon I got to light out for the Territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she’s going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can’t stand it. I been there before.”

— Mark Twain. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

ONE

1. “Playing with the Mountain”

In 1965 the Beat poet Gary Snyder accompanied by his poet-friends Philip Whalen and Allen Ginsberg decided to conduct a ritual circumambulation of Mt. Tamalpais in Marin County, California just across the bridge from San Francisco.i Their intention was to honor the natural and spiritual presence of the mountain. As Snyder described it:

“Remembering my trails around Tam [that he had hiked in the early to mid 1950s] I thought I would consecrate Tamalpais as a sacred mountain for future generations to do the same kind of pilgrimage on” (Real Matter 134).

Accordingly, on the morning of October 22, 1965, a day chosen because “it just happened to be the day we could all get together” (124), the three American Buddhist poets met at the parking lot of Muir Woods National Monument just off Highway One and set off following the Dipsea Trail that crosses a creek and then rises steeply through a lush forest. Here and there as they traversed clockwise the quite varied terrain of this remarkable northern California landscape, they paused to honor place and process by reciting poems and chanting sutras.

Creations are numberless, I vow to free them. Delusions are inexhaustible, I vow to transform them. Reality is boundless, I vow to perceive it. The awakened way is unsurpassable, I vow to embody it.ii

At various “stations” along the route (Snyder’s poem lists ten; Whalen’s poem lists eight), the company paused for recitations and observations.

How were these stations chosen? Freely and playfully, it appears. According to Snyder: “We just felt the magic vibrations. We decided on them the day that we walked it, by being finely tuned” (127).

Snyder and Whalen characterized these ceremonial gestures as “playing with the mountain.”iii Yet, like all true play—the play of children, the play of drama, music, or the (inter)play of wind and wave and sunlight—a certain gravitas held sway, a purposeless purpose. It was a gesture that Friedrich Schiller might have appreciated or perhaps endorsed.iv

As Whalen said:

Well, you know, I think that in some respect or other it is about getting Buddhist tradition or feeling established in this country, where it is so foreign, where it is so disconnected from anything real… [Circumambulating Mt. Tamalpais] was entertaining, and people might pick up on the idea. (Real Matter 134)

If you build it, will they come?v

TWO

2. St. Joseph of Arimathea by Wm. Blake

It is a bright and cheerful sunrise in northern California, March 19, 2001—the feast day of St. Joseph. My son Jonathan and I are speeding down Interstate 80 to Mt. Tamalpais. I called in sick, and we got an early start. Jonathan and I made our first circumambulation of Tamalpais in the early 1990s when Jonathan was eleven. The route these days is better known.

Jonathan’s at the wheel. I am reading aloud from Jack Kerouac’s novel, The Dharma Bums, a book dedicated to Cold Mountain poet Hanshan.vi I am reading the chapters toward the end of the book where Kerouac and Snyder, shortly before Snyder’s departure to Japan to study Zen Buddhism, sneak away from a three-day party to hike together one last time on the trails that crisscross Mt. Tamalpais.

The scene is the 1950s. Buddhism and most especially Zen Buddhismvii has taken root in the soil of American poetic imaginations. It’s been happening for several decades.viii Japhy and Ray discuss Buddhism as they walk the Marin trails and shake off hangovers.

Kerouac is disturbed. Raised a French-Canadian Roman Catholic, he struggles to resolve the intellectual contradictions between a Christian outlook and Zen.ix

“Japhy,” he says (Japhy Ryder is the name for Gary Snyder in The Dharma Bums) “do you think God made the world to amuse himself because he was bored? Because if so, he would have to be mean.”

Japhy is nonplussed. His childhood was not like Jack’s. Reared in the wilds of Oregon outside any orthodoxy of any Church, he can’t find much meaning in Kerouac’s question.

“Ho, who would you mean by God?”

“Just Tathagata, if you will.”

“Well, it says in the sutra that God, or Tathagata, doesn’t himself emanate a world from his womb but it just appears due to the ignorance of sentient beings.”

“But he emanated sentient beings and their ignorance too. It’s all too pitiful. I ain’t gonna rest till I find out why, Japhy, why.”

“Ah, don’t trouble your mind essence. Remember that in pure Tathagata mind essence there is no asking of the question why and not even any significance attached to it.

“Well, then nothing’s really happening then.”

He threw a stick at me and hit me on the foot. (201)

THREE

3. We Pick up a Hitchhiker

As Jonathan and I arrive at the empty parking lot at Muir Woods, I say to my son Jonathan, a religion major at Reed College in Portland, Oregon (where Snyder and Whalen went to school): “This is life, imitating art, imitating life, imitating art . . .”

Jonathan grins. It’s important that we get an early start. Pay attention! The hike is fourteen to sixteen miles, depending on detours, give or take. And we want to allow time for “celebrations and cogitations” and lunch and some journal writing and other important BS. This is not a clocked affair; it’s more of a meander. A river.

Indeed! In an essay called “Walking,” Henry David Thoreau developed similar Beat notions in lectures given repeatedly in New England in the 1850s.

I have met but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks—who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering: which word is beautifully derived from “idle people who roamed the country in the Middle Ages, and asked for charity, under the pretense of going a la Sainte Terre,” to the Holy Land, till the children exclaimed, “There goes a Sante-Terrer,” a Saunterer—a Holy Lander. They who never go to the Holy Land in their walks, as they pretend, are indeed mere idlers and vagabonds; but they who do go there are saunterers in the good sense, such as I mean. Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre, without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home but equally at home everywhere. For this is the secret of successful sauntering. He who sits still in a house all the time may be the greatest vagrant of all: but the saunterer, in the good sense, is no more a vagrant than the meandering river, which is all the while sedulously seeking the shortest course to the sea. (295)

FOUR

4. A Glastonbury Romance?

At the rough plank bridge that crosses the stream that separates the parking lot from the Dipsea trail that leads up the mountain, I pause and clap my hands twice, a habit I learned from Aikido. “I’m awake; you’re awake.” That’s the intention. “Something’s happening!” But do we notice?

Jonathan and I trudge up the steep mountainside, through ferns and forest and poison oak. I start to breathe more deeply. I’m in shape, but my left knee is sore from surwari waza practice.

Silent during the initial steep ascent on the Dipsea Trail, I start to free associate. My thoughts spiral to Parzival. I’m teaching Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival at the once vibrant now-defunct Rudolf Steiner College on Friday evenings this spring semester, and I think about Parzival and Galahad and Glastonbury and the Wound.

At the beginning of the European Christian era, Joseph of Arimathea sauntered with assorted family, women, and hangers-on from the Holy Land toward a sacred mountain. According to the medieval account by Robert de Boron, Joseph’s family carried with them the sacred Grail chalice that had caught the blood of Christ Jesus during the crucifixion. Legend tells us that the Grail chalice eventually came to rest in or near or under the sacred mountain at Glastonbury, where Joseph planted a sacred thorn tree by striking his staff into the soil of Wearyall Hill.

Another Grail narrative comes to mind: this one from Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival. In Book Five of that adventure, after Parzival fails to ask the right question during his first visit to the Grail Castle, Wolfram writes that “his adventures now begin in earnest.” Between Books Five and Nine in the poem, when Parzival gets a second wind and second chance, he spends a lot of time roaming around. He saunters, as it were, and bums it across the Territory. We don’t hear much about this walkabout. Instead, in Wolfram’s poem, Gawain handsomely steps forward. Parzival shows up now and then, but mostly he’s in the scenery, sauntering, spiraling, searching, biding his time.

FIVE

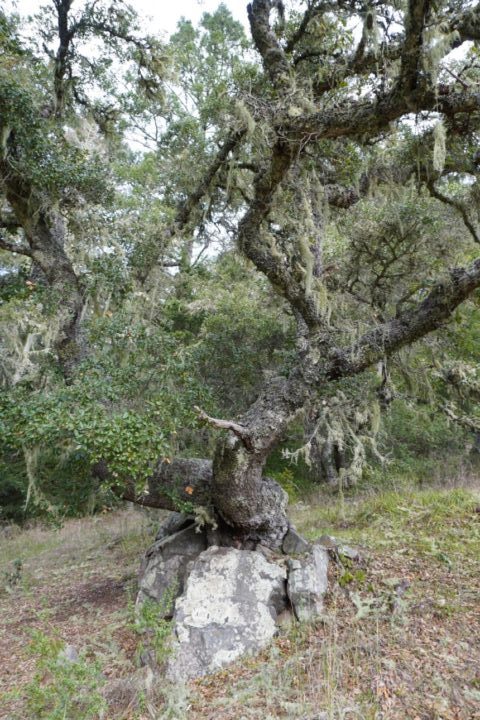

5. Tree in Rock

Jonathan and I arrive at a station on the route, and we take a brief pause. The station has the name Tree in Rock (or sometimes Oak and Rock) because a live oak tree native to California grows intrepidly from a rock. A sword in stone?

We clap and make acknowledgement, and then we continue up a steep trail through the woods to emerge at a magnificent vista meadow from which we can see the Pacific Ocean all the way to Asia, one might imagine. To the south along the coastline, we espy San Francisco in the factual here and now.

We sit in the Circle in the Grass and take a few pictures and have a snack. Then we move north and uphill until we arrive at a Greek-style amphitheater set into the mountain among some trees.

SIX

6. “Buddhism is very physical . . .”

Life imitating art imitating life imitating art . . .

The mirror-play of narratives in my mind (Parzival, Gawain, St. Joseph, Mary of Egypt, Thoreau, Gotama, St. Francis, Japhy, Ray) appeals to my sensibility as a dreamer. The narratives shimmer like a magic wonder glass through which I appraise this Glass Mountain on which we saunter.

Ray and Japhy also arrived at this amphitheater once upon a wrinkle in time. This Mountain Theater looks Greco-Roman, although it was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression. Theatricals, plays, and musicals have been staged here. The acoustics are good. The stone seats face out over hill and wood toward the distant metropolis. Kerouac described the setting as an “outdoor theater, done up in Greek style, with stone seats all around a bare stone arrangement for four-dimensional presentations of Aeschylus and Sophocles” (206).

I take out my copy of The Dharma Bums and read aloud.

The two companions in the novel, Japhy and Ray, wax poetic at this “Roman” ruin. They “sat and watched the silent play from the upper stone seats,” the book tells us. In the old country, ruined theaters such as this are remnants of mystery cults and temples. Have Jonathan and I become some shadow-chorus?

Japhy is inspired. He clearly enjoys the play of nature, and he resents the arrival of a noisy actor—aka some self-important Faustus filled with metaphysics who out-herods Herod. Japhy finds emptiness the truest drama. Is it not, perhaps, an authentic shining of original mind . . . a Lichtungx . . . and he extols an “unpeopled watershed, wet snowy mountains fading into dry pine mountains and deep valleys like Big Beaver and Little Beaver with some of the best virgin stands of red cedar left in the world.” (206).

“Actually, Buddhism is very physical,” Philip Whalen said in an interview about Tamalpais. “It’s very complicated and at the same time very straightforward, very simple. So, here is this mountain, which the Native Americans held in some regard, and then here is this Buddhist tradition of going to the mountains and walking around them, meditating, reciting sutras. This was something to do, something that you actively, physically and mentally, of course—do.” (135)

My son and I eat some apricots and chat. We sit on the stones of the amphitheater and look out toward Mill Valley and Sausalito. The spirit of Alan Watts floats in the breeze and tickles us.xi

I turn to another passage from Kerouac’s novel. I read the part where Japhy says to his conflicted Christian friend (later to die of alcohol abuse in the care of his widowed mother . . . a “son of the widow”xii . . .)

The closer you get to real matter, rock air fire and wood, boy, the more spiritual the world is. All these people thinking they’re hardheaded materialistic practical types, they don’t know shit about matter, their heads are full of dreamy ideas and notions. (206)

SEVEN

7. Cold Mountain

Japhy, like Henry David, longed for a better way. He wants to get his hands on the right stuff.

“These woods are great here in Marin, I’ll show you Muir Woods today, but up north is all that real old Pacific Coast mountain and ocean land, the future home of the Dharma-body. Know what I’m gonna do? I’ll do a new long poem called ‘Rivers and Mountains without End’ and just write it on and on on a scroll and unfold on and on with new surprises and always what went before forgotten, see, like a river, or like one of them real long Chinese silk paintings that show two little men walking in an endless landscape of gnarled old trees and mountains so high they merge with the fog in the upper silk void.” (200)

The novel I am reading, I tell my son Jonathan, is dedicated to “Cold Mountain”—or in other words, to Hanshan the legendary 8th century Chinese Taoist Zen hermit who lived in a cave like Milarepaxiii and practiced “crazy wisdom.” Hanshan is celebrated worldwide, and he exerted great influence on contemporary North American poetics, especially in this neck of the woods.

In another section of the novel, I find a passage where Japhy describes one of the Cold Mountain poems he (Snyder) is translating in the middle 1950s.

Cold Mountain is a house, without beams or walls, the six doors left and right are open, the hall is the blue sky, the rooms are vacant and empty, the east wall strikes the west wall, at the center not one thing . . . (202)

And then, I produce . . . a Miracle! The Time Being demanded it.

On a handy cellphone, I play a recording of Japhy aka Snyder reading the very same poem that Kerouac reported in the book.

The spirit of Alan Watts floats in the breeze and tickles us.

EIGHT

8. Uriel’s Treason!

We saunter on. At Rifle Camp we find a snaky path that follows the western slope.

“Are we on a circumambulation or on a pilgrimage?” Jonathan inquires.

As a student of religion at Reed, he understands that western literature has a long relationship to the gesture of the pilgrimage and to the character of the pilgrim on some adventure to some Great Place.

“Dante is the great artist of pilgrimage, making the journey to firsthand experience an ideal in art and life alike, and inspiring countless artists and pilgrims to imitate him.” (The Life You Save May Be Your Own)

“It is a problem of circle and line,” I begin to think.

Thoreau’s fellow poet and doughty Grail‑companion, Ralph Waldo Emerson, wrote a poem in which he related how at one time in the distant past Uriel the archangel of the summer season refused to acknowledge line or linear development as a determining factor in the universe: “Line in nature is not found / Unit and universe are round.” Like Prometheus, Uriel got into a whale of trouble for his opinion. He got gaslighted. But Emerson developed the notion into a poetics.

Ernst Lehrs first drew my attention to Emerson’s famous poem, and I find the memory again on this day of St. Joseph on Tamalpais as I peer through the magic glass of literature, imagination, and remembering.

Uriel, Lehrs told me, tried his best to argue some common sense with the archangels. He made the case for wiggliness, but the other archangels, sober, strict, systematic, linear thinkers, said: “Dude. No Way!”

“This was necessary and what man needed for the development of his Ego in striving toward its goal on earth. But in the present age man must learn to bring the cyclic principle into his life again, without abandoning the linear. It is in this sense that Rudolf Steiner has helped us to understand the festivals of the year. And so, the time has also arrived when Uriel can again come into his own.” (Lehrs 2)

Well, maybe . . . But right now, the Uriel team seems kind of down on the scoreboard, eh?

Regarding Jonathan’s question about circumambulation or pilgrimage, I decide to quote the original hippie. I say: “It’s as you like it.”

. . . tongues in trees, books in running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in every thing.

NINE

9. Collier Springs & Inspiration Point

Stations on the Way. We’re moving purposefully now, eager to reach the summit with enough time to rest and write poetry before the descent. It’s a long way down, almost three thousand feet, and since it’s the season of equinox, we don’t want to run out of daylight.

“WHERE IS THE MOUNTAIN?” wrote Philip Whalen, all caps.

Thus pondering, we reconnoiter an empty parking lot on East Peak.

I wax rhetorical. Have we “Conquered the Mountain?” Have we “Opened It?” Have we “Planted our Flag?” Have we struck our collapsible hiking poles into the heathen submissive soil of a Wearyall Hill?

While thus soliloquizing, Jonathan buys a red RC cola from a solitary red vending machine. We sit at a vista and look out toward Alcatraz. The cola is cold and sweet.

With sweetness as incentive, I cast the I Ching.

Before Completion (64) changing to Creative (1).

And then I write a poem.

Thus oracled, we progress. After a rugged drop through scrub and scree, we arrive at a fire road used by mountain bikers. From here we reach the fire station. We cross a trafficked road and join ourselves on the other side to a trail that snakes down from Mountain Home parking lot into the shadow of redwoods. We do not pause. We avoid the trail that leads to the Boy Scouts. On the long way down through Muir, I only enjoy the rhythm of my feet.

Another Beat and Buddhist, Lew Welch, a friend of Snyder’s who inspired the name of a zendo on San Juan Ridge, “Ring of Bone,” said this in an interview about Mt. Tam:

I have taken Mt. Tamalpais as my goddess in a very real way, like a priest takes a vow. I mean it. I ask her, Mt. Tamalpais, about this, about that, and I listen to what she tells me. A lot of people think I am being goofy about it, you know, or being poetic about it, but I mean it. I really mean it and the only way to say it is in the poetry. The praises. Prayer. (Golden Gate 161)

Practice is physical, rooted in ritual attitude of body/mind. Didn’t the romantics already tell us that already? “If poetry comes not as naturally as leaves to a tree it had better not come at all,” wrote Keats in a landscape from a distant time.

TEN

12. “Oeheim, waz wirret dir?”

It’s dark. We made it down.

Jonathan and I drive home on the interstate that connects the east of North America to the west, ocean to ocean.

I’m thinking about circles and lines and wiggliness and about the Grail—its transformations and perambulations—and about the future Maitreya, the Buddha who is to come, the Anointed One who sits in a chair to signify readiness to take action in the world, and about compassion and the problem of the so-called east and the so-called west, and about this Roman-spirited road we call I-80 and the internal combustion engine that makes it all possible, in a certain real sense.

Where is the sacred Homeland to be found?

What is this thing that human beings call the Grail?

“I ain’t gonna rest till I find out why, Japhy why.”

Parzival surely worked it out for himself once upon a time . . . this thing about circles and wiggliness. Parzival went on his walkabout to Munsalvaesche—circling and spiraling. Thus, the sacred Dharma makes its way.

This hidden human knowledge which is flowing “imperceptibly to begin with, into people’s ways of thinking” is like unto a river.

“Symbolically, this hidden knowledge, which is taking hold of humanity from the other side and will do so increasingly in the future, can be called the knowledge of the Grail” (Esoteric Science 388).

____________

Works Cited and Consulted

Batchelor, Stephen. The Awakening of the West. London: Thorsons, 1994.

Davis, Matthew and Scott, Michael Farrell. Opening the Mountain: Circumambulating Mount Tamalpais, a Ritual Walk. Emeryville, CA: Avalon, 2006.

Elie, Paul. The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2004.

Fields, Rick. How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America. Berkeley: Shambhala, 1992

Kerouac, Jack. The Dharma Bums. New York: Viking, 1958.

Lehrs, Ernst. “The St. John’s Tide Impulse and the Redemption of Science.” Photocopy of lecture given in 1958.

Powys, John Cowper. A Glastonbury Romance. Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1967.

Robertson, David. Real Matter. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1997.

Schiller, Friedrich. On the Aesthetic Education of Man. Trans. Elizabeth M. Wilkinson and L.A. Willloubhy. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

Snyder, Gary. Mountains and Rivers Without End. Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint, 1997.

—. Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2009.

Steiner, Rudolf. An Outline of Esoteric Science. Trans. Catherine E. Creeger. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1997.

Watts, Alan. In My Own Way: An Autobiography. New York: New World Library, 2007.

Whalen, Philip. Selected Poems. New York: Penguin, 1999.

Thoreau, Henry David. “Walking.” The Great Short Works of Henry David Thoreau. New York: Harper, 1982. 294-326.

Welch, Lew. Golden Gate: Interview with Five San Francisco Poets. Ed. David Meltzer. Berkeley, CA: Wingbow Press, 1976.

Wolfram von Eschenbach. Parzival. Trans. Helen M. Mustard and Charles Passage. New York: Vintage, 1961.

Images in the Text

- “Sunrise on Mt. Tam” photo by Bruce Donehower

- “Joseph of Arimathea Preaching to the Britons at Glastonbury” by William Blake

- Henry David Thoreau

- “Entering the Way” photo by Bruce Donehower

- “Tree in Rock” photo by Bruce Donehower

- “Mountain Theater” photo by Bruce Donehower

- “Cold Mountain” photo by Bruce Donehower

- “Jerusalem, plate 100” by William Blake

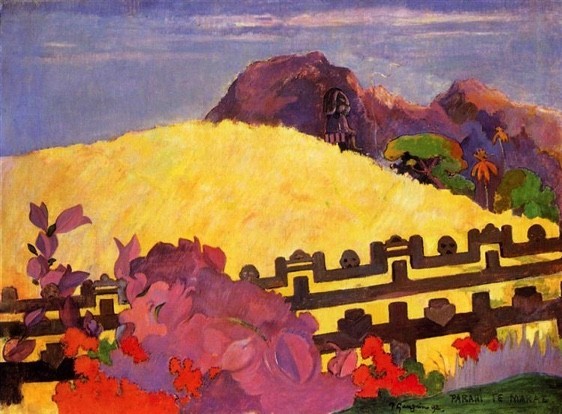

- “The Sacred Mountain” by Paul Gauguin

- Parzival / Wolfram von Eschenbach

Thoughts After the Hike (Conversations with the Living and the Dead)

A ritual breathes and lives with fresh performance, and each fresh performance lives differently from the last one you have in mind. The wiggly nature of Nature, as Emerson observed, resists ruling.

I’ve done this hike on Tamalpais many times over more than a quarter century, sometimes with a friend, sometimes with a group, sometimes solo. One year, when I needed recentering after a crisis, I did the hike solo several times. Each hike is unique, although the route is a settled gesture.

In November 2021, at the festival season of All Souls and Dia de los Muertos, I organized a poetic ritual on the mountain for friends and members of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities of the School for Spiritual Science in North America who meet regularly via Zoom in Fair Oaks. Our group is fortunate to include several poets. I explained the ritual to my poet friends and invited them to write a poem or two for the occasion. I asked that the poem be written during the festival of All Souls. I felt that this seasonal festival, when the veil between the worlds wears thin, was very important to the gesture.

I took the poems and read them on the mountain and made a video of the event. Some poems were read at sites chosen from “Scripture”—by that I mean, the improvised Scripture that Snyder and his friends created when they marked out what they thought were power points along the route. But script and Scripture soon got tossed aside during the day of the hike, and I followed my imagination, intuition, common sense, and the teachings of the mountain. The landscape spoke; the power points had shifted; and wiggly Nature had its own ideas of how she should be entertained.

Our 16-mile “circumambulation” occurred on a Saturday. On the next day Sunday, I went back to the mountain with my wife and son, and we shot more videos spontaneously as the spirit moved us.

May the viewer flourish!

Celebrating the Mountain: An All Souls Festival of Poetry on Tamalpais

Concerning the text

An earlier version of this essay appeared in the Yearbook of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities of the School for Spiritual Science (Verlag am Goetheanum: Dornach, 2002) and the Newsletter of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities of the School for Spiritual Science in North America. The present essay has been edited and revised in the light of research and the many experiences that have occurred during the past two decades.

The republication of this essay inaugurates the “Poetry in Landscapes” initiative of the Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities of the School for Spiritual Science in North America, 2021.

Endnotes

i Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen each wrote poems commemorating the event; Snyder’s: “The Circumambulation of Mt. Tamalpais;” Whalen’s: “Opening the Mountain, Tamalpais: 22:x:65.”

ii This translation of the Four Great Bodhisattva Vows is the version used by Upaya Institute and Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

iiiSnyder: “See, all of those stops on Tamalpais were like playing with the being of the mountain, nothing fancy about it.”

Whalen: “Certainly play is the operative word here, because that is a great deal of the feeling.”

Snyder: “You don’t have to take superstitions literally. Superstitions are metaphors for playful ways of seeing the world.” (Real Matter 132)

iv “And so at last, to state it clearly and completely, the human being plays only when she is human in the fullest sense of the word, and is only a complete human when at play.” Schiller, Letter 15 from Letters on the Aesthetic Education of the Human Being.

v Paraphrase of the famous quip “If you build it, he will come” in the American baseball movie Field of Dreams.

vi Hanshan has a prominent place in these proceedings because, as the character Japhy says in Kerouac’s novel: “he was a poet, a mountain man, a Buddhist dedicated to the principle of meditation on the essence of all things, a vegetarian too by the way though I haven’t got on that kick from figuring maybe in this modern world to be a vegetarian is to split hairs a little since all sentient beings eat what they can. And he was a man of solitude who could take off by himself and live purely and true to himself.”

vii The influence of Tibetan Buddhism had yet to make itself felt. The Chinese annexed Tibet in 1950-51. The Dalai Lama fled Tibet in March 1959. Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche fled Tibet in April 1959. Naropa University in Boulder Colorado was founded in 1974. These are just a few examples, of course. Historian Arnold Toynbee opined that the so-called arrival of Buddhism in the west “may well prove to be the most important event of the twentieth century.” Buddhism is of course a nineteenth century term invented by Europeans who observed something they didn’t quite grok, yet. They were like a “stranger in a strange land,” one might imagine.

viii For a survey of the history and influence of Zen Buddhism in North America, see How the Swans Came to the Lake, or for a more inclusive history of western reception of Buddhism, you might start with Stephen Batchelor’s The Awakening of the West.

ix The 20th century literary influence of American Catholicism (Thomas Merton, Flannery O’Connor, Dorothy Day, Walker Percy) has been explored, for example, in the book The Life You Save May be Your Own, as has the related 20th century phenomenon American Buddhism, cited earlier. One might ask: “What about American Anthroposophy?” Or is this a Zen oxymoron? The work of Henry Barnes comes to mind: Into the Heart’s Land (SteinerBooks, 2013).

x https://web.stanford.edu/group/archaeolog/cgi-bin/archaeolog/2006/09/01/the-clearing-heidegger-and-excavation/

xi A book that floats to mind is Watt’s autobiography with the tongue in cheek title: In My Own Way. Here’s a typical quip: “This also explains why I had always felt a strange difference of style between things churchly and things natural, for it struck me that the God worshipped in Church could no more have designed nature than Euclid could have written Finnegans Wake. Small wonder, then, that I came out buffeted and bruised from the experiment of trying to straighten out my wiggly nature to pass the narrow postern of Saint Peter’s Gate.”

xii A term used in the Mysteries. Parzival was a “son of the widow,” for example.

xiii Milarepa: Tibetan mahasiddha and poet.

11.24.20