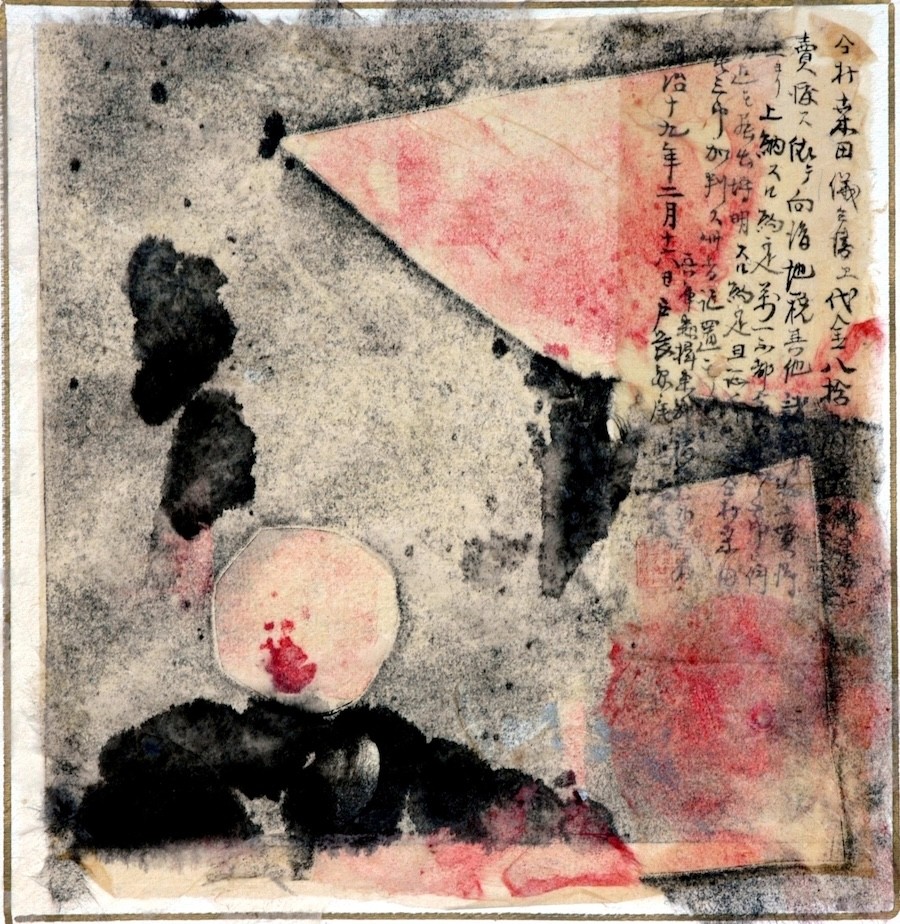

Artwork: “Monolith X” by Marion Donehower

At the Section meeting on February 24, 2024, we discussed the topic of Literary Modernism in respect to Threshold Experiences and Soul Loss. A variety of twentieth-century modernist poets and novelists were mentioned. This essay by Albert Steffen, although not discussed directly in our meeting due to limitations of time, speaks to the topic we considered.

The Poet and the Dead

“There were epochs in the evolution of mankind in which the relationship with the dead was more important than with the living. The resting places of the dead were not merely graves for their physical bodies, but also dwellings for their spirit-souls. As such they were built more permanently than their earthly houses. They were erected according to measurements which were read from the positions of the stars and the movements of the sun. In the cosmos, whose image they reflected, the human beings, who passed through the gates of death, met the gods, who never crossed the threshold of birth. The heavenly hierarchies, into whose ranks the departed were upraised, ordered the earthly community which assembled before the altar. Through the temple doors, the dead, honored as heroes, strode into the field of human action, gave laws, founded festivals, taught agriculture, prepared bread and wine and themselves lived in the sacramental meal.

“But the living were still bound.

“Today, now that the mysteries are being renewed, the relationship with the dead has changed. It must be founded on the freedom of the living. Nothing compels the living to seek out the dead. The consciousness of present-day man which awakens through the senses, becomes empty when their impressions are withheld and memory fades away. Longing hollows the soul. Thinking consumes it. In his relationship with the departed, he who is left behind, if he is not to lose himself, must become an active giver instead of a receiver. But it is just the nothingness to which he sees himself exposed which enables him to give of his own being, out of the fullness of his ego. Love alone is capable of this, love which is won on earth, and which has freed itself from the body. It is founded on the good, which one has selected in clear consciousness.

“But, for the dead, what is—good? That which corresponds with his development. To give him the good means: To enter lovingly into his path of evolution. One does this when, in one’s own soul, one follows his path to the spirit. As soon as he has crossed the threshold, the one who has died sees his life’s tableau. He sees his deeds, feelings, and thoughts from the vantage point of his ego which passes through deaths and births. He strides backward through his past life, ordering it according to his eternal individuality which is preparing a future life on earth. He constructs this future life according to the human measurements with which the gods provide him. In their divine company he traverses his path of destiny through the universe, into which he expands his being, in order to build up the germ of his new body. Therefore, it is knowledge of the universe with which the living man, who loves him, must go to meet the dead. Only as a thinking being inhabiting an earthly body is he able to achieve this. And he can transmit it only as a free act of his own decision.

“His gift returns transformed as picture, word and being, so that the giver himself is blessed. On this fact is founded the giftedness, scarcely regarded up to now, of future artists. That which is a general experience to men of conscious insight who unite themselves in freedom and love with the dead, is the poet’s task to portray in particular. He enters into the manifold destinies of the dead. Inexhaustible in their variety, they appear before him. It is above all up to him to reveal those moments, undreamed of by present-day humanity, in which the dead work into earthly life.

Out of his moral imagination, the poet today must depict how the dead, as occasional adjutants of destiny, play a part in untimely deaths, “fetching the living,” as the folk phrase goes. He should know that they receive this task because they did not follow their own intuition in the life which they have just completed, but obeyed instead commands which violated their conscience. They failed to assume responsibility for themselves and thus are not able to serve the salvation of others.

“But the poet also knows how spirits tarry beside sickbeds and bring about recovery. They are the spirits of those who did selfless good in life.

And he accompanies the dead, who pass from west to east and east to west, in order to share in the work on the soul development of mankind by forming and dissolving the essential characteristics of the folk-being of those who fell in war. The poet grants satisfaction to the dead when he creates a genuine tragedy; the departed themselves live in the fear, the compassion and the purification, because they come to awareness after death of the humanity which they have surrendered. Now they are otherwise oriented than in life. While experiencing their destiny in retrospect, they have crossed the climactic line and themselves inspire the course of the dramas to which the poet gives form. The latter discovers themes for centuries ahead. They come to him from the dead. If they do not speak with him, he must be silent. Everything depends upon the inner participation which he brings to meet them.

“In general, it may be said that nothing furthers humanity that is not wrested from the spirit. A decision which is taken merely out of intellectual considerations leads always to an uncertain situation. It runs a lame course. This holds true especially for art. One cannot create the slightest scene, even out of the most profound knowledge of the technique of the drama, as long as one is not endowed with the power of the word. The world wants to become word, grounded in knowledge. Through the word, it wants to be transformed into living spirit. And the poet wishes to create that higher reality which those who have died already experience. He seeks community with them, not to escape the earth, but in order to help save her. The dead, as supersensible figures, are prototypes for his poetic creation.

Poetry of the future must be both death-sacrament and life-festival, a bridge from here to yonder, a pathway to the spirit.”

====

A selection from the book Der Genius des Todes by Albert Steffen, 1943, Verlag für Schöne Wissenschaften.

(Trans. Henry Barnes, from Albert Steffen, Translation and Tribute, Adonis Press, 1959)

02.27.24