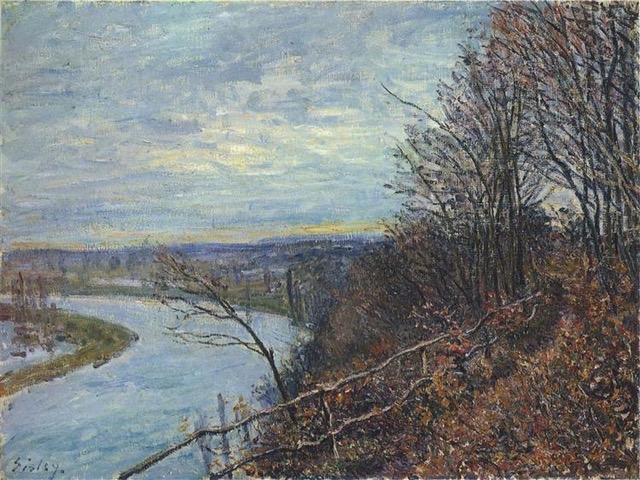

“November Afternoon” by Alfred Sisley

Here is a summary of the recent Section for Literary Arts & Humanities meeting of the local group in Fair Oaks, CA. This meeting occurred on November 14, 2020 via Zoom.

“At a Glance . . .”

- On November 20, members and friends have decided to attend the online production of The Comedy of Errors produced by Falcon’s Eye Theater in Folsom, CA. Because of this special event, we will not have a meeting on November 21. You will need to purchase a ticket. You can do that at this link: purchase your tickets

- Jean Yeager and Tess Parker are hosting an online writer’s salon on November 18. For information, contact: programs@anthroposophy.org

- We briefly discussed the sequence of meetings between now and December 19. We discussed the possibility of an online salon during Advent when we hold our final meeting for 2020

- Bruce will give a Section presentation to the Faust Branch this Wednesday, November 18 at 7:30 pm. “Novalis & The Healing Art of Fairy Tale.” The event will include the performance of the Novalis fairy tale “Hyacinth and Rosebud.” To join the Faust Branch Zoom Meeting: Zoom Link / Meeting ID: 893 0389 3792 / Passcode: 298030

“Tell me more . . .”

We began the meeting with a fragment by Novalis:

“Life must not be a novel that is given to us, but one that is written by us.”

From here we moved to a discussion and consideration of the characters in the writings of Novalis and Hermann Hesse. We noted that with both authors the heroes follow the promptings of conscience on their path to awakening. They rely on mind, conscience, and aesthetic sensibility (with perhaps a dash of good humor). This reliance on aesthetic sensibility is important. In both Hesse and Novalis — as with Schiller and other writers in the lineage we have studied recently — Beauty is the bridge between Body and Mind. Art is the praxis that builds this bridge. We referenced Rudolf Steiner in this context: for example, his lectures The Arts and Their Mission, among others. We reviewed again the emphasis that Novalis places on poetry and the realm of the poet. As noted in previous meetings: for Novalis, the way of poetry is not a course in learning how to write beautiful verse: it is the way to becoming authentically human. From the standpoint of magical idealism, the spiritual world is a How not a What. Novalis urges us to cultivate the sort of sensibilities and abilities that he writes about in his novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen and elsewhere in his fragments — for example, the fragment with which we began our meeting: “Life must not be a novel that is given to us, but one that is written by us.”

“Two Souls, Alas!”

The discussion of Beauty as a bridge between Body and Mind — art as a praxis that may help to resolve the apparent dichotomy of Body and Mind — this discussion led us briefly to consider the mission and purpose of the Section for Beautiful Sciences, as our Section is called literally in the German. As in previous meetings, I tried to situate Hesse and Novalis within the context of the secular humanist literary tradition that began with the European Renaissance. Some scholars of the tradition argue that this secular humanist literary enlightenment is unique. Be that as it may, it is certainly arguable that the characters in Hesse and Novalis exemplify ideals of this tradition. In their quest and questionings toward spirit they do not rely on any Institution, or Teaching, or Master, or Sacred Book. (The wise old woman in the fairy tale “Hyacinth and Rosebud” burns the mysterious stranger’s special book, for example.) The characters in Novalis and Hesse steer by the light of clear thinking, conscience, and aesthetic sensibility. Eros is an important part of their world. Recall, for example, the importance of Eros in Klingsohr’s fairy tale in Heinrich von Ofterdingen.

A Game of Drones?

We had time to take a look at Hermann Hesse’s final novel The Glass Bead Game in which Hesse depicts an idealized society of intellectuals called Castalia. It is easy to miss the tone of irony in Hesse’s final novel. Hesse does not present Castalia uncritically. And Novalis would certainly ask: “Where is Eros in that world of Mandarin intellectuals mindful only of Spirit, Idea and Ideal?” As we know from reading Klingsohr’s fairy tale, when Eros enters our affairs all hell breaks loose — worlds thaw and warm, change begins to bubble, and Sophia finds her rightful balance of respect . . . well, gradually, maybe. Does this not have something to do with Beauty as bridge between Body and Mind — and the capacities we nourish with art and poetry — combined with clear thinking and conscience? The main character Knecht in Hesse’s novel The Glass Bead Game might be read as a fuller portrait development of the character Narcissus. Narcissus was a medieval monk and abbot, and Hesse had no interest in writing a book about such a Christian character — no more than he had interest in writing about a Buddhist character, although the title Siddhartha misleads some readers. But Hesse’s art and inclinations required him to explore the nuances and complexities of a Narcissus — a person devoted to duty and spirit — who at last finds the “perfection” of his spiritual discipline incomplete — who at last must “give himself to the world” in a gesture of love that includes in its willingness to die a higher devotion, one might argue.

The Glass Bead Game is in some ways a more challenging novel than anything else Hesse wrote. One of the remarkable aspects of the book is how seriously it presents the themes of meditation and reincarnation and karma. Hesse’s insights here are precise and knowing and experienced – based on study and practice. Another remarkable aspect of the book, as noted, is its subtle tone of irony and sly humor that accompanies the “high-brow” concerns. One might even argue that the novel is a kind of insider joke. Hesse and Novalis are similar insiders. They might have shared winks.

“Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”

We digressed in several directions last night. One of those directions was toward Bollingen and Zurich, Switzerland. (The picture above is a picture of Jung’s tower at Bollingen.) A question arose concerning Hesse’s acquaintance with Carl Jung and Hesse’s familiarity with Jungian psychology. This led to some thoughts concerning Jung’s connection with Goethe — and in particular, the importance of the drama Faust for Jung. Mention was made of Jung’s autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections and to a footnote at the end of the book where a reference is made to Jung’s tower in Bollingen.

Here is Aniela Jaffe’s footnote. The name Philemon refers in part to the characters Philemon and Baucis at the end of the Faust drama (Part 2). The two die as a result of Faust’s activities. But the name Philemon has other important connotations for Jung (and for Novalis), as we might be able to explore in other meetings if we proceed in this direction.

“Jung’s attitude [toward the significance of Faust] is shown in the inscription he placed over the gate of the Tower: Philemonis Sacrum—Fausti Poenitentia (Shrine of Philemon—Repentance of Faust). When the gate was walled up, he put the same words above the entrance to the second tower.”

Footnote by Aniela Jaffe, from Memories, Dreams, Reflections by C.G. Jung

I am the poet of the Body and I am the poet of the Soul,

The pleasures of heaven are with me and the pains of hell are with me,

The first I graft and increase upon myself, the latter I translate into a new tongue.

— Walt Whitman, Song of MyselfLet the poet’s realm be the world, pressed into the focus of his time. Let his plan and execution be poetic—i.e. poetic nature. He can make use of anything—but he must amalgamate it with spirit—he must make of it a whole . . .

— Novalis, from The Poet’s Realm, 1796