Here is a summary of the recent weekly Section for Literary Arts & Humanities meeting of the local group in Fair Oaks, CA. This meeting occurred on October 17, 2020 via Zoom.

Meeting Summary

We started our meeting a bit early at 6:40 to allow more time for greetings and conversation. At a little after 7:00, we began with a reading from The Calendar of the Soul by Rudolf Steiner followed by announcements and some introductory remarks concerning The Apprentices of Sais by Novalis.

During the announcements, we made the decision to dedicate our meeting on October 31 to John Keats. October 31, in addition to being Halloween and the Eve of All Saints, is the birthday of John Keats, a poet we studied when we were working on British Romanticism during last year’s “kitchen talks.” October 31 looks like a good date to premiere the new website for our local group, I am thinking also. Several members immediately offered to prepare a reading of poems for the October 31 event. Karen offered to read a poem by Keats; Dan offered to read Eliot’s poem The Hollow Men; Marion and I will prepare something to share — and others? “Come As You Were” was mentioned as a theme for the evening. Between now and late October, if you think of a poem or brief prose reading that you’d like to share with the group, please contact me.

This will be Keats’s 225th birthday. He is a junior to Novalis, who was born in 1772. Keats and Novalis, in a certain sense, can be seen as two literary luminaries at the beginning and end of the romantic era. Each died young, before the tremendous promise of their talents had been fully expressed. Perhaps in future meetings, we can compare and contrast these two poets a bit more. This would lead us to interesting observations concerning the similarities and differences between British and German romanticism. The previous “kitchen talk” lectures on British Romanticism, prior to the Covid crisis, gave us a good foundation for such a conversation — and the intensification of our work since the crisis — our months-long weekly study of Novalis, for example — has given us more insight into the era and its personalities — and their importance for our situation.

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone . . .

— Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

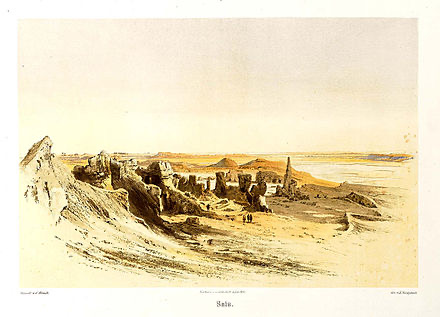

Ruins of Sais, Egypt

L’Académie de Sais

We then segued to Sais. I suggested that a good way to find entry into The Apprentices of Sais is to start in the middle with the fairy tale “Hyacinth and Rosebud.” And I suggested that the best way to approach that fairy tale is to hear it read or recited — repeatedly. Novalis is very clear: he values poetry and fairy tale very highly. Apprentices, however, is filled with a swirl of contrasting ideas. It is a galaxy of conversation! Reading it reminds me of being back in college as a freshman or sophomore (half wise/half stupid) who is giddy with the excitement of Mind. Gosh! All those conversations and points of view come argued with dazzling velocity. We’re swept away — first one way, then another. And then, apropos college — we are apparently privileged to be enrolled at the University of Sais in ancient Egypt! Who can resists the glamor! Is that a statue of Isis that I pass each day on my way to Comp Lit 101? Right next to Thoth? And who is that learned priestly hierophant whose sagely demeanor I doth discern tottering about the campus? Is that truly the Revered Master who bears upon his cloak of many colors the Key to All Mythologies?

In Novalis’ brilliant book, this concert of ideas concerning nature, cognition, the being human — art, destiny, poetry, and Free Will — come at us from all directions. It’s all quite a heady mix to make one giddy. At this time in his life, Novalis was enrolled at the Freberg Minining Academy — the MIT of its day, one might imagine. He was willingly and enthusiastically under the sway and influence of Abraham Gottlob Werner, director of the institution — revered for wisdom and insight into the mysteries of Nature. Werner is a person we should discuss, if we have time. I suppose Novalis had a disciple’s predisposition for devotion — I am recalling here young Hardenberg’s previous devotion to Schiller, for example. This is an admirable quality that every Parzival might aspire to exhibit, one might argue. At any rate, the Apprentices can leave the head spinning, and it can easily tempt us to spin off into galaxies of conversation — thought universes scintillating and endless.

“Poor child, who has not yet loved!”

Thus, however, sound the introductory words to the fairy tale “Hyacinth and Rosebud” right in the middle of the chatter — in the midst of this galaxy of scintillating conversation. Reminding us, perhaps, of something essential?

We then discussed the figures of the Stranger and the Wise Old Woman of the forest. Both are initiators of the fairy tale’s young hero, Hyacinth. I suggested that we recall another young hero, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, whose “blue flower” dream comes after a decisive encounter with another mysterious stranger.

“I long to behold the blue flower. It is constantly in my mind, and I can think and compose of nothing else. I have never been in such a mood. It seems as if I had hitherto been dreaming or slumbering into another world; for in the world in which hitherto I have lived, who would trouble himself about a flower? I never have heard of such a strange passion for a flower here. I wonder, too, whence the stranger comes? None of our people have ever seen his like; still I know not why I should be so fascinated by his conversation.” — Novalis, Heinrich von Ofterdingen

From here we discussed Hesse’s novel Steppenwolf, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni. Mozart, as you probably guess, found entry to our meeting via Harry Haller, hero or anti-hero of Hesse’s Steppenwolf. In Steppenwolf, Mozart is the Revered Master at the end of the novel who “strangely” initiates Harry, who calls himself the Steppenwolf. Harry, in fact, is a stranger to himself and a strange annoyance to others. You might say that Harry is a virtuoso Outsider who rehearses repeatedly those ditties dear to the consciousness soul. “Poor child, who has not yet loved!” Well, Master Mozart sets Harry straight — in a crooked sort of way, excuse the pun. In Hesse’s novel, the Academy of Sais becomes the Magic Theater (of Mind) whose motto (contrary to Harry’s fond inclinations) is not “All Hope Abandon” but “For Madmen Only.” Meister Mozart has Harry laughed out of court — literally! Listen to what Mozart tells Harry at the moment of Harry’s initiation and insight. Poor child!

Mozart to Harry Haller:

“You have heard your sentence. So, you see, you will have to learn to listen to more of the radio music of life. It’ll do you good. You are uncommonly poor in gifts, poor blockhead, but by degrees you will come to grasp what is required of you. You have got to learn to laugh. That will be required of you. You must apprehend the humor of life, its gallows-humor. . . You would be ready, no doubt, to mortify and scourge yourself for centuries together. Wouldn’t you? . . . Well, I am not. I don’t care a fig for all your romantic atonement. You wanted to be executed and to have your head chopped off, you lunatic! For this imbecile ideal you would suffer death ten times over. You are willing to die, you coward, but not to live. The devil, but you shall live!” — Hermann Hesse, Steppenwolf

And so, as Narcissus advised young Goldmund: onward! Next week and following we will continue with Novalis, Hesse, Mozart, and other apprentices. And Gayle has agreed to make a presentation on the motif of the veil and the “lifting of the veil.” This is an important trope for Novalis — and it brings to a certain symbolic focus the theme of Mystery that we began to play upon last night.

“Someone arrived there who lifted the veil of the goddess at Sais. But what did he see? He saw, wonder of wonders, himself.” — Novalis

Meeting Extras

Here again is a link to a performance video of “Hyacinth and Rosebud” by Novalis from The Apprentices of Sais. Directions: Take once or twice daily before sleeping, preferably after a meal. Can be renewed without approval indefinitely.

Here, too, is a link to a PDF copy of the Hesse poem (in her own handwriting!) “Organ Recital” translated by Alice, which Alice presented at our last meeting. Thank you, Alice, for this splendid translation!

“Orgelspiel” by Hermann Hesse. Translated by Alice.

“In a work of art, chaos must shimmer through the veil of order.” — Novalis