Here is a summary of the recent Section for Literary Arts & Humanities meeting of the local group in Fair Oaks, CA. This meeting occurred on December 5, 2020 via Zoom.

“At a Glance . . .”

- On December 12 we will celebrate the completion of our work in 2020 with an online salon. Everyone will bring something of special value from the year’s work and will have five minutes or so to present to the group. Active participation is not required! Feel free to come just to enjoy the salon

- The last 2020 meeting for the local group is on December 19 for those who are free and wish to attend

- The Section will sponsor a Holy Night evening for the Faust Branch on December 31, New Year’s Eve. This evening will consist of an artistic presentation featuring music and A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

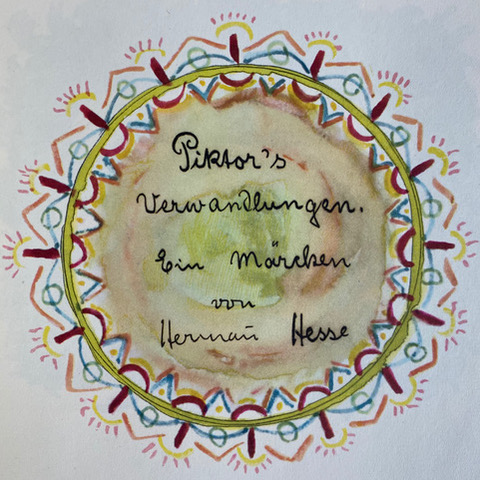

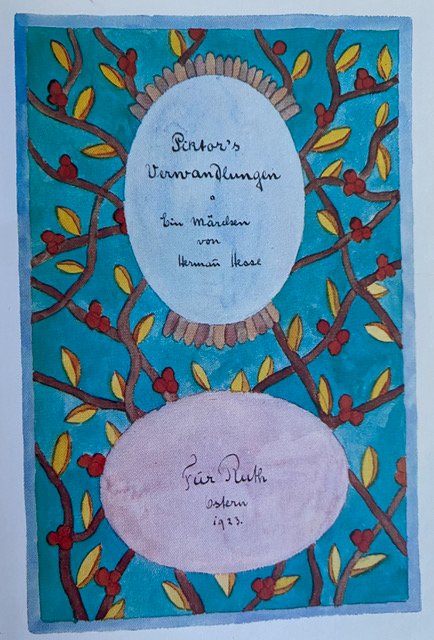

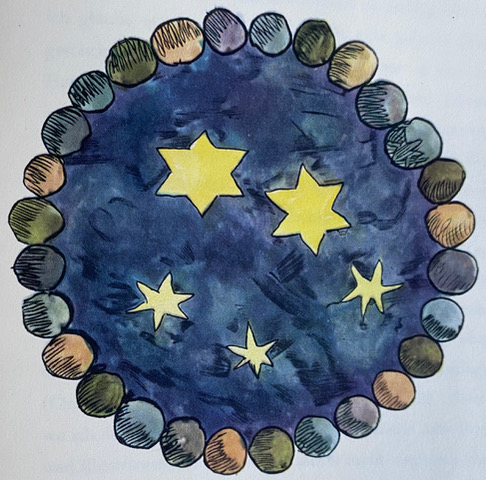

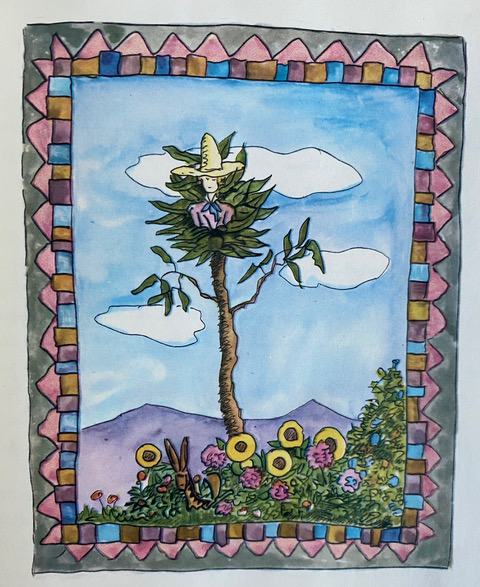

- Marion presented a fairy tale by Hermann Hesse: Piktor’s Metamorphoses. In addition to Marion’s reading, the presentation included original artwork by Hermann Hesse and an overview of the tale’s literary history and its importance to Hermann Hesse. We ended the evening with a discussion

English

German

“Tell me more . . .”

The Fairy Tale: Portal to Realms of Spirit

On the Books & Essays page of this website you will find a book whose title in English is “The Fairy Tale and Rosicrucians.” In the second chapter of the book, titled “The Brothers Grimm and the Impulse of Romanticism,” we find this intriguing quote on page 13.

“The genre of the art fairy tale suited the romantic attitude towards life because it included the world of wonder and allowed the free play of the imagination. The boundaries between reality, fantasy and imagination become very blurred. Ludwig Tieck did not draw a clear separation between fairy tales and novels, and by his definition fairy tales were “lovely admixtures of the terrible, the strange, and the childish.” You can certainly say the same about the fantastic stories by E. T. A. Hoffmann. For Novalis, on the other hand, the fairy tale was the epitome of poetry: “Everything poetic must be like the fairy tale.” And: “All fairy tales are dreams of a homeland that is everywhere and nowhere.” Such statements realign our view of the fairy tale and shift our appreciation of the images used in fairy tales. Instead of fanciful and arbitrary, these imaginations become true images of a noumenal spiritual world. Goethe’s fairy tale The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily (1795), which for Novalis was the great model for his fairy tale poetry, is a highpoint of such exact imagination.”

Over the past year, our acquaintance with Novalis has introduced the fairy tale as new subject focus for our work in Fair Oaks. We did not start the year 2020 with this intention, however. In fact, as far as I can recall, the local group has spent hardly any time on the fairy tale per se as a literary genre during the past ten years. But as soon as Novalis entered the circle of our attention, so too did the fairy tale.

A Golden Bough

Woven like a golden thread between the writings of Novalis and the writings of Hermann Hesse, we find the fairy tale. Hesse, following the indications of Novalis, practiced the art of the Kunstmärchen or art-fairy-tale. He wrote many original fairy tales — and he did so fully aware of Novalis the ideas Novalis held concerning the fairy tale. Hesse certainly had read the fairy tales in Heinrich von Ofterdingen, for he said that this novel was one of his essential books. The fairy tales in Heinrich von Ofterdingen are of course models, demonstrations, and invitations to practice the art. That is the spirit in which they are presented — for example by master poet Klingsohr to young Heinrich.

Rudolf Steiner’s many lectures on the significance of the fairy tale build upon the insights of Novalis and Novalis’ early romantic contemporaries. In fact, as we know from Rudolf Steiner’s repeated comments, the fairy tale is a vital and critical source spring for anthroposophy. I am referring, of course, to Goethe’s fairy tale The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily. This tale, written at the time of the early romantics in the 1790s, weaves itself throughout the symphony of anthroposophy like a dominant and all-determining leitmotif. It perhaps cannot be emphasized too often or too strongly how important were the years in which the fairy tale genre occupied the attention of Novalis and the early romantics. Perhaps our group will have more time to look at this aspect in 2021.

For after all, it is only a hundred years ago (September 25, 1920) that Rudolf Steiner spoke these words at a preliminary address for the opening of the first Anthroposophical Course to be held in the Goetheanum, which memorialized the significance of the fairy tale for anthroposophy:

“I may say, it is actually so that it [Goethe’s fairy tale The Green Snake and Beautiful Lily] is the archetypal seed of this Movement [die Urzelle dieser Bewegung].”

And, as we know as well, it was on September 29, 1900 in Berlin that Rudolf Steiner inaugurated his work as a teacher of anthroposophy with his lecture on Goethe’s fairy tale (“Goethe’s Secret Revelation”). Rudolf Steiner called this Berlin lecture in 1900 “his first anthroposophical lecture.” These comments are from the book The Time is at Hand! by Paul Marshall Allen and Joan Deris Allen (Anthroposophic Press, 1995).

Piktors Verwandlungen

Piktor’s Metamorphoses is Hermann Hesse’s demonstration of the fairy tale, following Novalis and the early romantics. As Marion told us Saturday night: Hesse took enormous care to personalize this creation. He refused publication: preferring instead to create the book by hand. Moreover, he extended the tale’s meanings with original artwork — much in the manner of William Blake who thought that significant works of literature required this personal touch — a marriage of word and visual art. (See previous meeting summaries from early 2020 for a discussion of William Blake and Blake’s artwork/poetry.)

Blake and Hesse might be seen, in this regard, to be practitioners of the art of the illuminated manuscript — such as this art might come to be practiced in the Age of Michael. We know of course with what loving spiritual devotion Christian monks practiced this art of the illuminated manuscript. Here however with Hesse and Blake, we find a significant shift in consciousness and a new emphasis. Blake’s and Hesse’s spiritual and artistic praxis finds resonance with those early monastic manuscripts, certainly — but Blake and Hesse lived in an entirely different spiritual age — with different demands and procedures. “The time is a hand” for a new revelation, a new mythology, we are told. Novalis and the early romantic contemporaries heed this summons — as does William Blake. One hundred years later, this same spirit of the age inspired Hesse. The illuminated fairy tale, Piktors Verwandlungen, is one result, one might argue.

A Bird with New Feathers

For the purposes of Marion’s work with the Hesse fairy tale, I was forced to do a new translation of Hesse’s tale. The existing English translations are either chopped up and disordered or else they are flat footed, we felt. In our opinion, none capture the nimble word-play and whimsical rhymes and poetry of Hesse’s German — and such word foolery is very important to the sense and meaning of Hesse’s tale. I will aim to make this translation available to friends in the coming year.

But in the meantime, for those who read German, here is a link to the Suhrkamp edition of Piktors Verwandlungen: click here.

And, in regard to the playful use of language exhibited in Hesse’s fairy tale, here too Hesse follows the indications of Novalis. In a previous meeting we discussed the brief fragment Monolog in which Novalis characterized his attitude toward language and the use of language by the poet. I included this extended fragment in an earlier meeting summary (Sept. 26, 2020), but I think it may be interesting to view it again.

From Monolog by Novalis (1798)

“Speaking and writing is a crazy state of affairs really; true conversation is just a game with words. It is amazing, the absurd error people make of imagining they are speaking for the sake of things; no one knows the essential thing about language, that it is concerned only with itself. That is why it is such a marvelous and fruitful mystery – for if someone merely speaks for the sake of speaking, he utters the most splendid, original truths. But if he wants to talk about something definite, the whims of language make him say the most ridiculous false stuff. Hence the hatred that so many serious people have for language.They notice its waywardness, but they do not notice that the babbling they scorn is the infinitely serious side of language . . .” — Novalis

(Translated by Prof. Joyce Crick, London)

Crisis and Breakthrough

Marion’s presentation began with an overview of Hesse’s biography. She focussed on the middle years — 1917 to 1924, approximately. These were years in which Hesse went through a personal crisis of purpose and identity that led him to analysis with a Jungian therapist and later with Jung himself. The fairy tale Piktor’s Metamorphoses emerges from these years. In many ways this short fairy tale can be read as a companion book to the novel Siddhartha, which was written just beforehand. As Marion pointed out, Hesse completed Siddhartha following an extended period of writer’s block, and very soon thereafter he followed up quickly with Piktor’s Metamorphoses. The fairy tale tells the story of Piktor’s initiation. It is set entirely in the spiritual world. Hesse begins with an imagination of Paradise. Even the Serpent plays a role. We find here alchemical themes such as the Coniunctio Oppositorum. Hesse, like Jung and Novalis, was a student of alchemy and was familiar with alchemical motifs and symbology. He used these tropes self-consciously, as did Novalis. Piktor’s Metamorphoses celebrates a playful enlightenment of endless change and becoming that Schiller also drew attention to in his Aesthetic Letters, which we discussed at some of our meetings in previous years. Perhaps we can discuss Schiller’s book again in 2021 — especially in light of its very special relationship to Goethe’s fairy tale. If the human being becomes most human when at “play” — then, finding the knack and freedom to change and to transform playfully, as Piktor learns from his initiation, allows us to become most truly human, perhaps.

Marion’s discovery of this tale by Hesse and her devotion to presenting it to our local group led the two of us on an online search through German used bookstores (Antiquariat) in order to find old copies of the text. We wanted to see as much of Hesse’s artwork as we could afford. As mentioned, word and visual image are married in this illuminated manuscript, so called. The naive style of representation, although at first off-putting, gradually recommended itself. Hesse made each copy by hand — and he prized the handmade item greatly for its aura. (I use the word in the sense that Walter Benjamin used it.) Marion’s presentation last night included a reading of the tale accompanied by artwork from facsimile editions that we obtained. As Marion read, I screen shared pages of the text so that participants could follow the translation and see the images. I did something similar with Blake at the beginning of the year, but that was before Zoom — and Blake, of course, needed no translation.

A Never-Ending Story

And so, onward! Personally, I find this unexpected emphasis on the fairy tale to be enormously vitalizing and rewarding. I am very thankful that Novalis led us here during our time of enforced solitude and outward isolation. Indeed, I hope that in 2021 the work on the fairy tale will continue and will intensify — for I believe, like Novalis, that the fairy can bring us healing inspiration. And, it certainly helps us to avoid that dreaded dead end of the literary researcher: scholarly petrification and idolization of the “Correctly Interpreted Text.” Egad! Yikes! That loud roaring sound I hear — is someone snoring? Rather death from a thousand paper cuts! Or as Keats exclaimed:

“O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene . . .”

I wonder if the fairy tale, taken in the spirit of Novalis and his bonny platoon of bold companions, might be a focus for our local group’s Section work as we move forward into 2021? May the reader flourish!

“The world is a riddle, and the human being is its solution.”

— Rudolf Steiner

“The spiritual world is in fact already open to us. It is always open.

If we were to suddenly become so alive and supple to perceive it,

We would perceive ourselves in the midst of the spiritual world.”

— Novalis“Piktor’s happiness faded like a dream. He began to feel the weight of years, and he more and more rehearsed the tired, venerable, serious, troubled demeanor that some of us may observe in very old trees. Why, anyone can in fact detect this mood on any day she pleases in horses, birds, people – in all sentient beings actually. Whatever or whoever lacks the knack for change finds herself stunted and estranged, sadly shorn, beauty forlorn.”

— Hermann Hesse