“Grace is the beauty of form under the influence of freedom.”

— Friedrich Schiller, from the essay Grace and Dignity (1793)

This famous quotation by Friedrich Schiller relates very importantly to our Section meeting on February 19, 2022. The words roll off the tongue quite easily . . . seemingly so familiar that we seldom pause to meditate the deeper meaning.

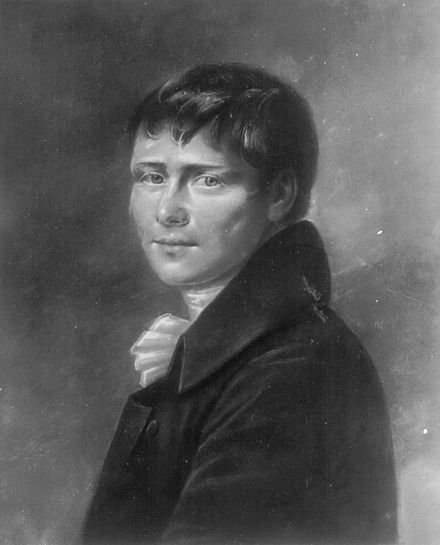

Last night directed us toward such meditation when Marion introduced us to one of her distant relatives, Heinrich von Kleist.

Heinrich von Kleist (1773-1811) is an author who has not yet joined the conversations in our Section meetings. Kleist arrived last night via the medium of his famous little essay On the Marionette Theater. Marion summarized the essay and led us into a discussion.

As mentioned a few times previously, Marion facilitates our local Section-inspired Fairy Tale Group which presently finds itself in the midst of a project to create puppets that we intend to use for movies and/or dramatic presentations. This puppet making activity has taken under its wings several arts: music and drama, sculpture and visual arts, and of course creative writing. Kleist was a dramatist, and our recent meeting presentations such as Fred Dennehy’s on “The Actor’s Process” have brought theater and drama back into the conversation in our Section.

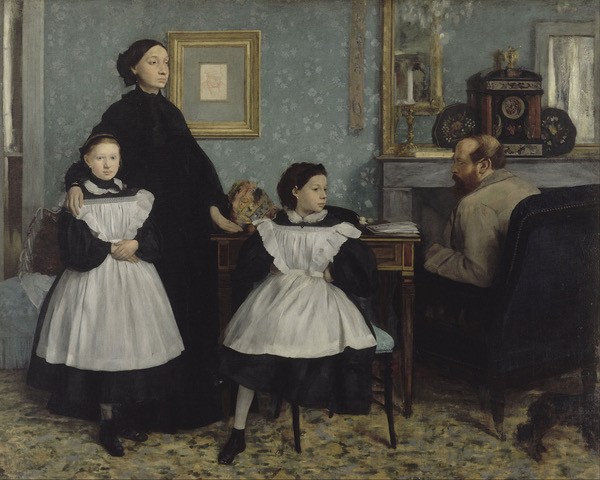

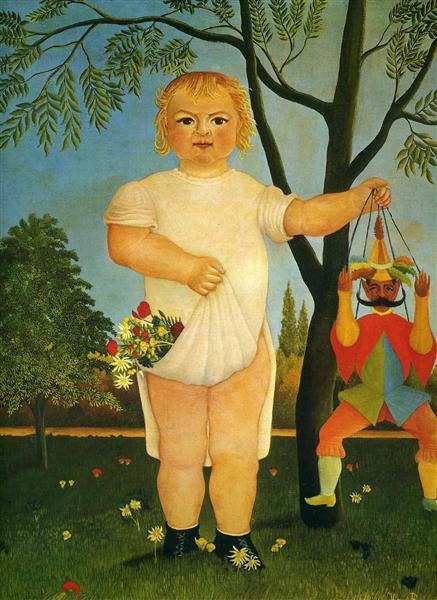

“Child with a Puppet” by Henri Rousseau, 1903

The Gesture of Beauty

Kleist’s little essay On the Marionette Theater has received much attention for what it has to say to practitioners of movement arts. These persons include eurythmists, martial artists, and dancers, among others. As Marion explained last night, she first came to appreciate Kleist’s essay On the Marionette Theater in respect for the insights that she could apply to Tai Chi and Aikido. In a famous passage in the essay, Kleist tells the story of a captive bear who nonetheless demonstrated an uncanny ability to parry an opponent effortlessly. The bear, like a refined Zen swordsman sensei, exhibited a mastery of movement that a clumsy self-conscious human might achieve (maybe!) only after decades of dedicated and painful practice in a dojo. And, when a clumsy, self-conscious human achieves such moments of “mastery” after those long decades of practice in a chosen discipline, these moments feel more like Grace than achievements of a striving ego. Do they not?

“. . . the bear’s utter seriousness robbed me of my composure. Thrusts and feints followed thick and fast, the sweat poured off me, but in vain. It wasn’t merely that he parried my thrusts like the finest fencer in the world; when I feinted to deceive him he made no move at all. No human fencer could equal his perception in this respect. He stood upright, his paw raised ready for battle, his eye fixed on mine as if he could read my soul there, and when my thrusts were not meant seriously he did not move.”

— Heinrich Von Kleist, from On the Marionette Theater

A Graceful Lemniscate of West and East

Marion read the famous conclusion of Kleist’s essay more than once — for it is here in the conclusion that Kleist reveals his theme: the mystery of Grace. And she referred us to another book: Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery. In her discussion of this little classic, she drew our attention to the similarities between the Zen Buddhist tradition, as represented in Herrigel’s book, and the themes that we find in Kleist’s essay.

“Now, my excellent friend,” said my companion, “you are in possession of all you need to follow my argument. We see that in the organic world, as thought grows dimmer and weaker, grace emerges more brilliantly and decisively. But just as a section drawn through two lines suddenly reappears on the other side after passing through infinity, or as the image in a concave mirror turns up again right in front of us after dwindling into the distance, so grace itself returns when knowledge has as it were gone through an infinity. Grace appears most purely in that human form which either has no consciousness or an infinite consciousness. That is, in the puppet or in the god.”

— Heinrich Von Kleist, from On the Marionette Theater

“You must hold the drawn bowstring,” answered the Master, “like a little child holding the proffered finger. It grips it so firmly that one marvels at the strength of the tiny fist. And when it lets the finger go, there is not the slightest jerk. Do you know why? Because a child doesn’t think: ‘I will now let go of the finger in order to grasp this other thing.’ Completely unself-consciously, without purpose, it turns from one to the other, and we would say that it was playing with the things, were it not equally true that the things are playing with the child.”

— Eugen Herrigel, from Zen In the Art of Archery

What Does Grace Mean for the Literary Arts and Humanities?

Grace is the controlling theme of Kleist’s essay, one might argue. We can say that a person moves gracefully and exhibits beauty in respect to levity and gravity. Or we can say, using theological rhetoric, that a human being lives most authentically by the power of Grace. But, in a more secular humanist mood and context, one might say that Grace is the condition of the quality of being human that makes possible authentic poetry. And recall that for Novalis and romantics who share Novalis’ outlook, the Poet is not just a facile rhymer or one who spins graceful tales; she is the spiritually authentic and awake, free and ethical human being.

In German, our Section has the name Beautiful Sciences. We have spent much time in our meetings in discussion of Beauty and Aesthetics (especially within the context of early romanticism), but much less time if any in discussion of Grace. But perhaps we should? In our Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities, what do we aspire to? In the most basic and simplistic terms of our practice, you might say that from a literary standpoint we aspire to the demonstration of a graceful style. “Graceful style?” That sounds laughable these days, does it not? But in fact, this ideal of the cultivation of a graceful style (the exhibit of a “beautiful soul”) was once a guiding light for character development in pedagogy. Why, for example, was young Will Shakespeare drilled every day at the grammar school dojo for hours and hours in the tedious practice of writing graceful Latin imitations — a discipline that would send most of us howling in panic to our life coaches, I dare say. But on the other hand, some of us will spend years and decades drilling ourselves in tedious katas or at the ballet barre or at the piano keyboard, etc. . . . all for the hope of a transcendent moment of Grace.

Our discussion digressed into other important themes in Kleist’s essay, such as the paradox of the trans-human entity who exhibits more grace than the biological human being. Recall, for a moment, our previous several discussions of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein. Ironically it is the monster (the trans-human AI creation of Dr. Viktor Frankenstein) who exhibits moral grace and intellectual beauty, one might argue — all the while as this “monster” is persecuted for its unlawful parody of the being human and for its “otherness.” In Kleist, such a monster is the puppet or marionette, which in Kleist’s example exhibits more grace than the human dancer, the essay argues. We find related examples of trans-humanism in E.T.A. Hoffmann. It is a romantic trope.

“If poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree it had better not come at all.”

— John Keats

Our dreams still practice the sacred arts

Of story-telling and divining

Each one its own genre and drama

The genius of sleep reveals

Her purpose in vivid pictures

Hidden as stars during the day

How can we sleep knowing

That magic world is there

Frightening us into the courage

To believe in fairy-tales

In which all our dreams

Are coming true as if

Like marionettes we could

Be moved by the grace of gods

— “Dreaming Valentine” by Peter Rennick

Here is an audio recording in English of Kleist’s essay On the Marionette Theater. Translation by Idris Parry.

Or: Click this sentence to read a PDF of Kleist’s essay On the Marionette Theater.